- AI

- A

Sovereign AI, honor killings, and R&D deficit. Where is the Indian economy heading today?

We continue to talk about the successes and failures of the independent Indian economy. In the previous article, we showed what happened to the country's economy from 1947 to 1991 - during the era when members of the Nehru-Gandhi clan tried to launch its growth by administrative-command methods.

In the second half of the 1980s, changes began in the country, which led to the final abandonment of flirting with state socialism and the liberalization of the economy in 1991 (how familiar!). In this text, we will talk about the modern stage of India's development — and what prevents the country from becoming a new China.

How the liberalization of the Indian economy took place and what it led to

Since 1991, India has achieved a good rate of economic growth, which exceeds the values of the previous period. In 1947-1980, GDP grew by an average of 3-4%, and in the 1980s — by 5.5%. In 1992-2019 — already by 6.6%. S&P analysts expect GDP to grow by an average of 6.7% per year until 2031, and during this period it will almost double.

By the 1980s, the Indian National Congress (the party of Nehru and Gandhi) had largely exhausted its huge credit of trust, and it had to become increasingly involved in political competition with other parties, usually more right-wing both economically and politically.

The party began to suffer from splits, it had to form alliances with many smaller forces to retain power, and internal struggle intensified. In 1991, Rajiv Gandhi was killed by Tamil terrorists, and the party was headed by Narasimha Rao — the first prime minister not from the Nehru-Gandhi clan, who led the country for a long time.

Together with economist Manmohan Singh, who became the Minister of Finance, Rao went against the will of the majority of his party members. They launched large-scale liberal reforms - carried out large-scale privatization, reduced bureaucratic barriers for business, and created favorable conditions for foreign investment and financial capital.

Contrary to the fears of the left, the economy, which at that time was in deep crisis and on the verge of default, not only did not collapse but also achieved unprecedented growth rates. Direct foreign investment increased from $240 million in 1990 to $3.58 billion in 1997. And by 2008, it reached $43 billion.

Thanks to market liberalization and infrastructure development, almost any manufacturer had the opportunity to sell their goods in a market of several hundred million people. Farmers began to grow commercial crops more actively for sale in other states, increasing both yields and their margins.

From 1983 to 1999, the overwhelming majority of people, including representatives of the poorest segments of the population, more than doubled their consumption of fruits, meat, fish, and eggs, and also significantly increased their consumption of edible oils, vegetables, and dairy products.

Having freed themselves from the yoke of License Raj, bureaucracy, and other restrictions, Indians began to enthusiastically open small and medium-sized enterprises. It often happened that the descendants of village blacksmiths opened metal processing workshops, and the descendants of weavers opened hosiery factories. Wealthy landowners began to build small factories and plants, diversifying their businesses.

The economic revival has affected almost all industries — restaurants, hotels, transportation, construction. Thus, the share of "kutcha" houses in rural housing — huts without amenities made of clay, straw, unbaked bricks, and similar materials — decreased from 49% in 1988 to 17% in 2008. New industries such as domestic tourism and wedding halls for organizing lavish celebrations have emerged.

Rao increased investment in education and infrastructure. This was extremely important — the achievements of previous Indian governments in education, especially in the accessibility and quality of schools, were quite modest.

By the beginning of the 21st century, 43% of Indians did not even have primary education. The policy quickly bore fruit: if in 1980 an Indian studied on average only 2.5 years, then in 2000 — already 5.6 years, and in 2020 — 7.8 years. Today, Indians are obsessed with education like no one else in the world.

The Birth of Indian IT

In parallel, India was becoming an IT power. Government support for telecom and IT, along with the liberalization of regulation in these areas, began in the early 1980s — thanks can be given to Indira Gandhi, who in her last years in power was favorable to these areas.

Indian leaders of that period — both Rajiv Gandhi and Rao — were genuinely interested in digital technologies and soon infected the whole country with this enthusiasm. Therefore, by the time of liberalization in 1991, this sector was already quite independent and in demand abroad. But liberalization allowed these connections to be scaled and international outsourcing to be maximized and simplified.

The first major client of Indian software firms was Citibank, which settled in the Bombay IT cluster back in 1985 and formed Citicorp Overseas Software Limited (COSL). Soon the firm began selling its banking software solutions to other banks — first in Asia and Africa, and then in developed markets.

Western corporations such as Microsoft and SAP, as well as investors, poured into the Indian market. The share of the IT-BPM sector in the economy grew from less than 1% of GDP in 1997 to 7.5% in 2023.

India under Modi

The new economic configuration proved to be effective and viable, so subsequent governments largely maintained this course. From 2004 to 2014, the country was led by Manmohan Singh, one of the architects of liberalization.

Initially, it was supposed to be Sonia Gandhi, the widow of Rajiv Gandhi, who would become the prime minister. But she wisely gave way to the talented economist.

In 2014, the Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian People's Party) won the elections. Narendra Modi became the Prime Minister, who has been ruling the country for 10 years. This year, his party won the elections for the third time, and Modi will likely remain in power at least until 2029. From a political perspective, the victory of the right-wing conservative party has changed a lot — but not in the economy.

One of the most original projects of the Modi era is the "sovereign artificial intelligence" program. As part of this plan, the government wants to maximize the monetization of AI and extract as much benefit from the technology as possible for all sectors of the economy, including agriculture and industry.

In addition, it is planned to create a giant platform for AI training, where all anonymized data about Indians collected by government agencies will be accumulated. It is assumed that Indian AI companies can buy such datasets for training models and other tasks.

Given the country's large population and relatively high level of digitalization, the project could significantly change the balance of power in the AI market. If, of course, Indian companies have something to train on these datasets.

What problems have not been solved

Poverty and inequality

The main problem with poverty in India is that it is very difficult to adequately assess.

According to the UN, over the past three decades, the lives of the vast majority of Indians have improved.

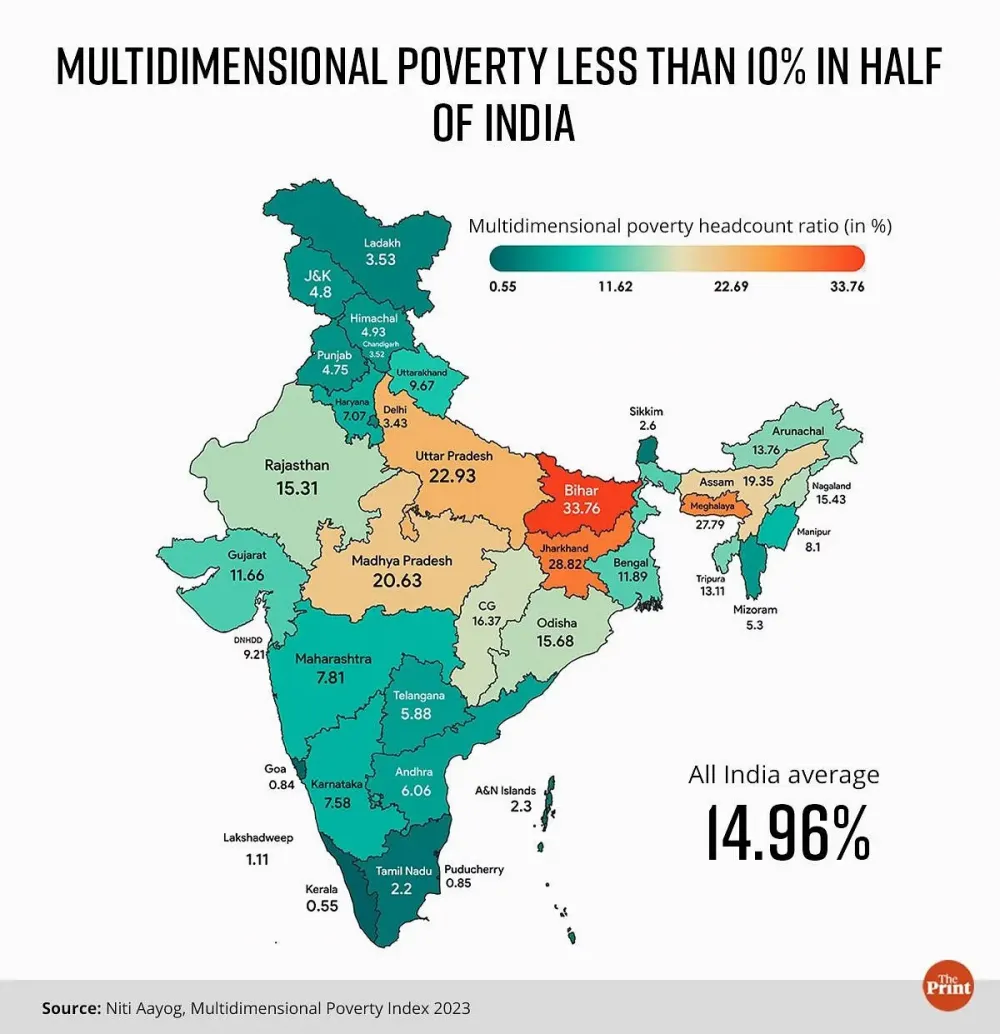

UN researchers have developed a "multidimensional poverty" rating — it assesses the level of poverty across 10 dimensions of deprivation in three groups: health, education, living standards. If a person scores more than ⅓ of the indicators, they are considered poor.

In 2005-2006, 55.1% of Indians — 645 million people — lived below the "multidimensional poverty" line. By 2019-2021 (the rating is labor-intensive, researchers are forced to use data from different years), more than 400 million people had escaped it.

As of 2021, 230 million Indians — only 16% of the country's population — live in "multidimensional poverty". And according to the 2024 report by the Indian government, made using the same methodology, only 11% of Indians are in "multidimensional poverty".

However, the last census in India was conducted in 2011 — and without its data, all poverty studies cannot be complete. Government methods of assessing poverty and economic growth rates in the republic are very often criticized for bias and the intention to present the situation in a better light. Many experts say that Modi and his economists skillfully juggle numbers, embellishing the true state of affairs.

The author of this text himself observed how, on the eve of the G20 summit in Mumbai, ugly slums along the route of the delegations are covered with huge posters and banners with greetings and uplifting slogans about India's prosperity — real Potemkin villages.

Even if the majority of Indians today do indeed live better than the formal poverty indicators, they are far from economic prosperity. Thus, the average city dweller in India consumes $42 per month, and in rural areas — $24.

Moreover, if you look at the distribution of property in the country, it becomes clear that inequality has only grown, and the beneficiaries of the country's economic successes are those who were already far from destitute.

In 2000, the top 1% of the richest Indians received a quarter of all income in the country, and in 2021 — already a third. The top 10% own 64% of the property — even more than under British rule, when this figure was about 50%. Today, India is the third country in the number of billionaires after the USA and China.

In 2000, the bottom 50% of Indians accounted for only 8.3% of income, and in 2021 — a meager 5.9%. Representatives of the poorest half own property worth just over 66 thousand rupees — less than $800. The average income of the poorest half is 4467 rupees per month, or $53.

Indian rich people have become much richer in recent decades and are not shy about demonstrating it. Recently, the whole world was amazed by the luxurious wedding of representatives of India's richest houses, Anant Ambani (his father is the ninth richest person in the world) and Radhika Merchant, whose celebrations lasted several months and, according to various estimates, cost $300-600 million.

In 2014, Ambani's fortune was $23.6 billion, and he was the richest person in India. He is still the richest now — but his fortune has since grown more than fivefold and is now $124 billion. Meanwhile, wages in India's agricultural sector, after adjusting for inflation, have not grown at all over the same 10 years.

Poverty in India is accompanied by traditional prejudices. The caste hierarchy is strongest in the poor provincial hinterland, where even today one can be maimed, raped, or even killed for an improper inter-caste marriage or even a symbolic violation of caste customs.

Such economic inequality divides a society that de jure rests on liberal and democratic values.

Recently, a video went viral on X, showing a fair-skinned, well-groomed Sikh landowner from the wealthy Jat landowner caste strolling through his farm, watching the work of dark-skinned migrant peasants from the poorest state of Bihar, and playing with a golden cane. To many, he resembled a plantation slave owner inspecting his slaves.

The growth of inequality is probably explained by the "Kuznets curve" — an economic law formulated by American economist Simon Kuznets back in the 1950s. According to it, as the economy grows and transforms from an agrarian to an industrial one, income inequality first increases and then decreases — the graph resembles the letter U. India is now at the bottom — but will it go up later?

Another answer — India spends only 3% of GDP on social programs, which is extremely low compared to other countries, for example, 15% in China and Brazil, and 20-30% in developed countries.

Inability to create new jobs

The leading post-industrial sector of the country is IT outsourcing. Once, Western corporations placed support services in India, for which it was enough to speak English fluently to get a job.

This, of course, has not gone anywhere (just like consumer goods factories in China). But today, quantity is rapidly turning into quality. The same corporations are already placing R&D centers in the republic. Indian companies develop architectures for about 20% of new chips.

IT specialists from this country win in any championships and programming competitions. Software from Indian IT giants such as Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services is used by European and American enterprises. There is no doubt that the demand for Indian IT products and services will grow, and they will play an increasingly important role in the global market.

However, less than 4 million people are employed in the Indian IT industry — about 0.3% of the population of the huge country. If you take all the workers associated with digital industries — it will be about 27 million. For a country with a population of 1.4 billion people — this is negligible.

At the same time, the unemployment rate in India has been rising in recent years. In June 2024, it was estimated at 9.2%, whereas in the decade before COVID-19, it fluctuated between 5.2-5.6%. Even in the COVID-19 year of 2020, it was only 8%. The worst part is that among the unemployed, young and educated individuals dominate. Youth (15-25 years old) make up 83% of the unemployed, and people with higher education — 66%. For ordinary intellectual job vacancies in the public sector and large companies, tens of thousands of applicants sometimes compete.

A common story in modern India is when engineers work as ordinary builders, and university graduates return to their parents' farms or engage in unskilled labor in the service sector, earning no more than $100-150 per month. Young teachers report that for the right to work in a private school or college, they are asked for bribes of around $4,000 — unimaginable sums for the vast majority of Indians.

In 2020-2023, 60 million new workers appeared in Indian agriculture. And this is very bad, as many of them are educated people who could not find work at home and returned to their native farm.

The young population is called India's main advantage in the global world — especially against the backdrop of rapidly aging China. But if this youth has nothing to do, the advantage turns into a problem.

The employment structure also does not look very encouraging. 52% of working Indians are self-employed, 25% work in temporary jobs, and only 23% are employed as permanent salaried workers.

But these are only those who are not working and looking for a job. The overall labor force participation rate in India is 50% in general and a dismal 25% among women. This means that three-quarters of Indian women are not engaged in either the formal or informal economy and are engaged in household chores.

Lack of own innovations

India's success in post-industrial sectors of the economy is mainly based on outsourcing. Only a small number of Indian companies, such as Infosys, create their own innovations and globally competitive intellectual property.

The rest serve Western corporations, which either buy breakthrough technologies from American and European scientists or create them themselves, but far from India. Such a business is doomed to create low added value and is unlikely to become the foundation for the country's leap into the big leagues.

The focus on service projects and the lack of stimulation of domestic R&D is one of the most frequent complaints against governments in recent years. Countries focused on rapid economic growth usually introduce weak patent regulation, effectively allowing their businesses to steal and copy technologies from other countries.

Governments often directly contribute to this — we have already reported on tekkix how China has built a system of scientific and industrial espionage to ensure innovative development.

But instead, the Indian government is investing huge amounts of money in projects that consolidate India's position as one of the links in global production chains. Links that cannot claim anything more than the status of a "world factory".

Former IMF Chief Economist Raghuram Rajan and Cornell University Professor Rohit Lamba provide this example in their book Breaking the mould. Back in the 1970s, a powerful pharmaceutical industry developed in India, which soon was able to produce quality generics.

In 1972, the Indian company Cipla released a generic version of the drug propranolol. The rights holder, the British company ICI, sued them. Cipla turned to Indira Gandhi, assuring her that the drug would help many Indians. She changed the intellectual property law so that the end product, i.e., the medicine, could not be patented, but the process of its production could.

Thus, if an Indian company found another way to produce the final medicine, it could do so legally. After that, many Western companies left the Indian market, as they could not compete with generic manufacturers, thereby opening the way for the independent development of the industry.

But in 1995, India joined the WTO and signed the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) — its provisions more strictly protected inventions from copying and extended protection periods. This was a huge blow to the Indian pharmaceutical industry — now Indian companies had to pay huge royalties for their generics.

Cipla leader Yusuf Hamid says that this decision was a betrayal — with the profit margin under such regulation, his company simply has no opportunities to invest in its own fundamental developments. This did not prevent Cipla from releasing a revolutionary HIV drug in 2001, which reduced the cost of treatment from $12,000 to $350 per year, making it accessible to countries like India. But overall, innovation activity in Indian pharma has slowed down significantly since then.

Today, the government supports national manufacturers, but a significant portion of state investments goes to projects with low added value. For example, in 2023, the Gujarat state government approved the construction of a Micron plant, which will create about 5,000 jobs for Indians. The plant will receive a direct government subsidy of $2 billion — it turns out that each job will cost $400,000.

Well, we are watching the successes of the Indian economy.

Free search, monitoring, and registration of trademarks and other intellectual property objects.

More content about intellectual property in our Telegram channel

Write comment