- Security

- A

Hacking a robot vacuum cleaner and spying on the owner in real time

A major home robotics manufacturer failed to address the security issues of their robot vacuum cleaners, even though they were warned about the risks last year. Without even entering the building, we managed to get pictures of the device owner. And then it got even worse...

Robot vacuums are moving uncontrollably in thousands of homes around the world. An ordinary Australian, Sean Kelly, also decided to buy one to ease household chores, as he and his wife have twins and a five-month-old baby. And he chose a model produced by the world's largest home robotics manufacturer: Ecovacs.

Sean settled on the flagship model Deebot X2, believing that with it he could count on the maximum security money could buy. Oh my sweet summer child, how wrong you were!

His robot turned out to be vulnerable to remote hacking, and Ecovacs did nothing despite receiving a warning back in December 2023.

In essence, it turned out that he had purchased a webcam that drives around the house and monitors his family. I called Sean to inform him of the bad news about his vacuum cleaner and asked if he would mind if I hacked his robot.

Honestly, I personally don't know how to hack equipment, I needed the help of Dennis Geese, a security researcher who has spent many years dissecting robot vacuums.

Recently, he found a way to take control of an entire range of Ecovacs robots, including lawnmowers and Deebot vacuums, using just a smartphone.

And he didn't even have to touch them - he could do it entirely via Bluetooth, from a distance of up to 140 meters. Gis announced his findings at a hacker conference in Las Vegas. I contacted him by email and asked if he could help me hack a robot vacuum cleaner.

"I can assemble a payload for you," he wrote back.

This will allow you to "run anything" on some Bluetooth-enabled Ecovacs devices, including Sean's flagship X2 model, which sells for $2500.

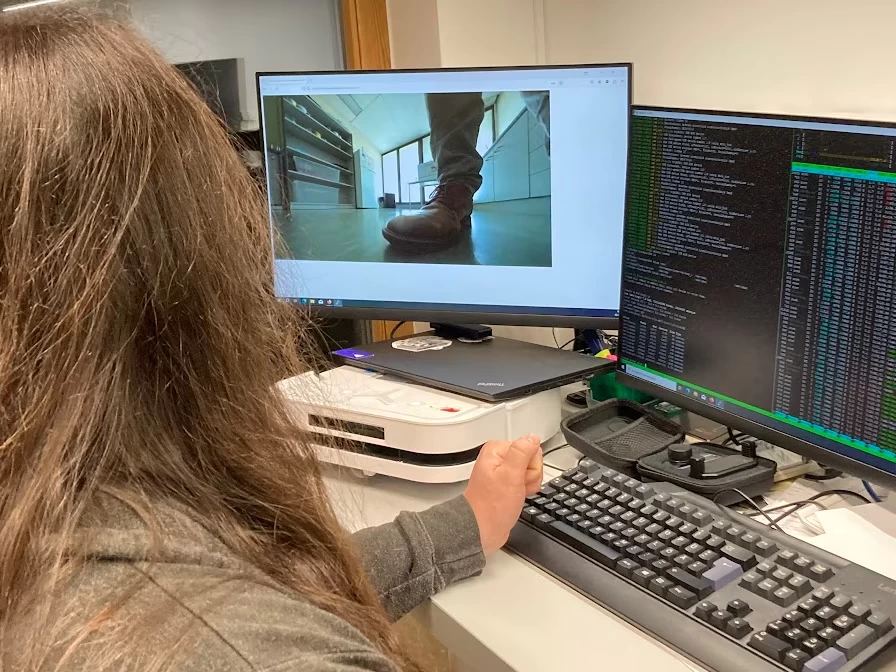

According to Gis, once I connect to the device via Bluetooth, I will have full access to the built-in computer and, accordingly, to all the sensors connected to it. "You will be able to access all logs, WiFi credentials, and full network access," Gis delighted me. So, I will be able to access the "camera and microphone nodes."

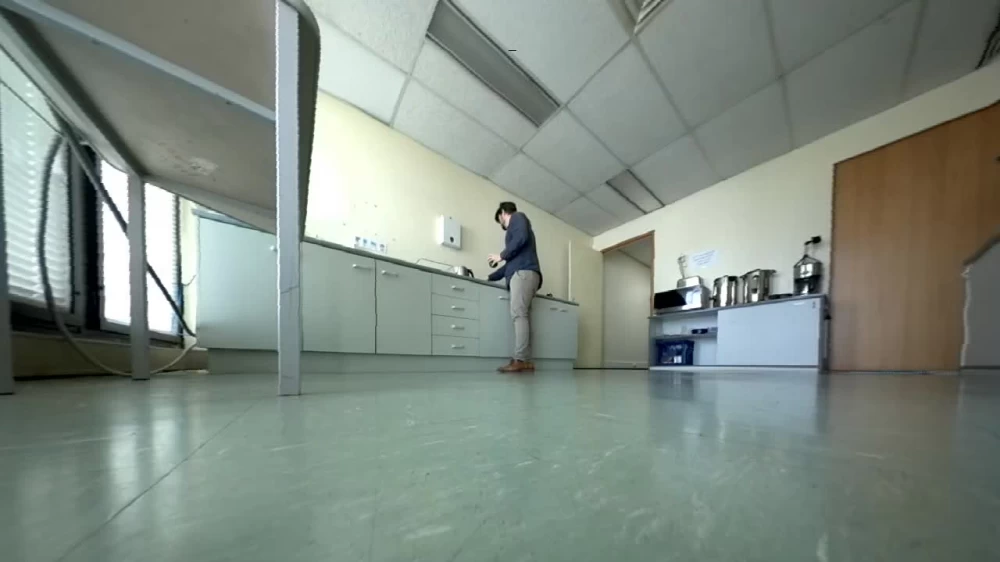

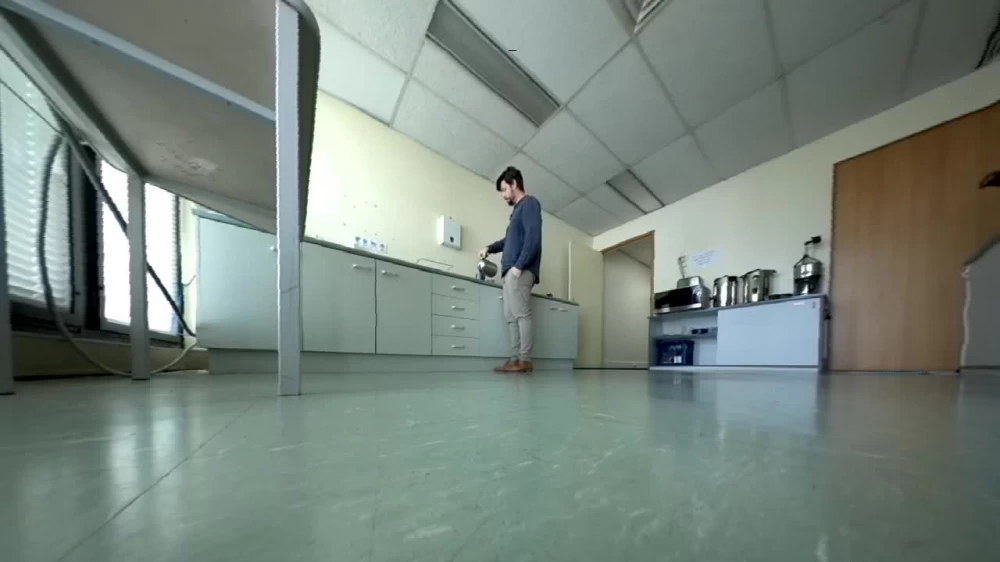

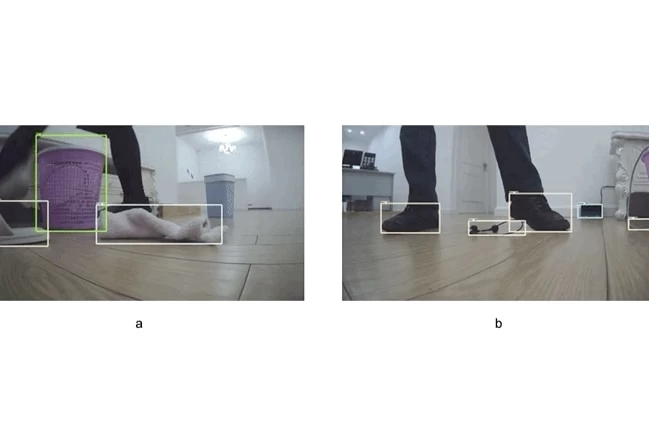

Sean's wife was categorically against us hacking the device at their home. So, we decided to test it in the office kitchen instead. So, on the fourth floor of a huge building with thick concrete walls, Sean plugs in his robot vacuum cleaner.

I am sitting in the park right outside the window. From this distance, the Bluetooth signal is weak; I have to move closer to the fence for a better connection. Sean's office is on a busy street near downtown Brisbane, and passersby give me strange looks when I raise my phone to the sky.

Soon, his device labeled "ECOVACS" appears on my phone.

And here we go.

The robot does not play the warning sound for "camera recording" start — it seems this signal is only played if the camera is accessed through the Ecovacs app. But Sean is aware and expects me to watch him, as he agreed to this less than an hour ago.

But he doesn't know that we added a secret feature. And when the moment seems right, we play a little prank. "Hello, Sean," says the robotic voice. "I'm watching you."

Sean's eyes widen when his robot says his name. He finds it both funny and unsettling.

“This is crazy,” he says, looking at the robot, as if he doesn’t recognize his own vacuum cleaner. The device has been crawling around his home for most of the year, potentially giving enterprising hackers a chance to spy.

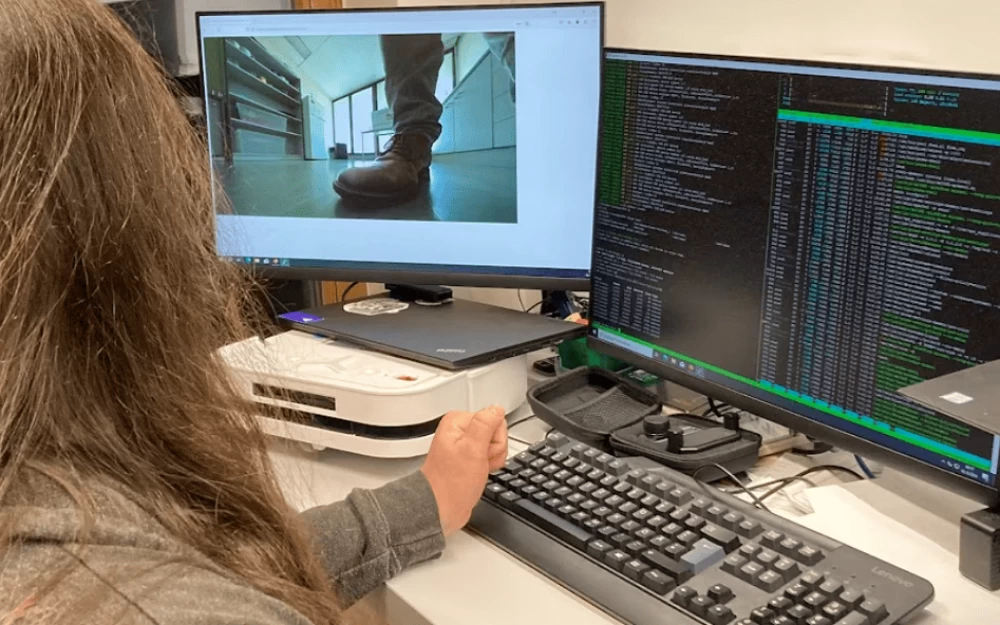

While I was connecting to Sean's robot from the park outside, a real hack was happening on the other side of the planet. In Germany, Gis stayed connected for a whole hour, helping pull the strings. There were several failed attempts, but then it worked.

— Done, I sent the [payload]. Did it work?

— Ha-ha, I’m in. Now let’s steal their darkest secrets.

Of course, Gis was joking when he talked about stealing Sean’s data. But he was completely serious about gaining access to the vacuum’s onboard computer. The photos were being sent to his server in the U.S., and he was viewing them (from his apartment in Berlin) at the same time I was. “Nice office,” he texted me.

“I was surprised that the robot was moving and had access to the camera,” Gis said later.

After I sent the start command via Bluetooth to gain access, neither of us needed to be near the robot to continue monitoring through its camera.

Not all the vulnerabilities that Gis discovered were equally problematic — for Ecovacs as well as for other brands. Many required physical connection to the robots or even disassembling them to get to the internals.

He does not report low-risk threats. But the one we were dealing with now was particularly sensitive. Gis quickly notified Ecovacs, stating that he had discovered a serious security vulnerability that could be fixed remotely. He did not disclose specific details because he did not want to transmit them over an unsecured channel, and has not yet published them publicly.

This was in December 2023. Ten months ago. But he still did not receive a response. The company later woke up and replied that they had accidentally missed the December letter. But for a company with a turnover of a billion dollars, which is currently the market leader, this is a bit alarming.

Gis's interest lies in gaining access to devices, not spying on the people using them. Nevertheless, it took him only a couple of hours to figure out how to take photos, send them to his server, and play his audio recording through its speakers.

At some point in our experiment, Gis jokingly suggested permanently disabling the vacuum cleaner's computer, thereby showing what harm he could actually cause.

— Okay, let me do something scary. Should I turn his robot into a brick?

— Ha-ha-ha, no, no. It's enough for us to just hack it.

In the end, we fixed everything. There were no traces left on Sean's device, and he took his robot home, puzzled by such a threat to his family's privacy. Now he throws a towel over the robot when it's not in use. The experiment was a wake-up call for Sean, but privacy risks in the modern world go far beyond a single product.

"People don't consider their dishwasher a robot," says Dr. Donald Dansereau, a senior lecturer at the Australian Centre for Robotics at the University of Sydney. "We live in a society flooded with cameras."

It is the robot vacuum cleaners that have received close attention because they are too noticeable. But in reality, cameras are everywhere, for example, in cars that fill the streets. And when cameras are everywhere, questions arise about how protected the footage is.

Initially, Ecovacs stated that its users "should not be overly concerned" about Giese's research. After he first publicly disclosed the vulnerability, the company's security committee downplayed the issue, stating that "specialized hacker tools and physical access to the device" were required to reproduce it.

It's hard to reconcile their statement with reality. All it took was my $300 smartphone, and I didn't even see Sean's robot until I hacked it.

Ecovacs eventually stated that it would address this security issue. At the time of publication, only some models had been updated to prevent this attack. But several models, including the latest flagship model released in July this year, remain vulnerable.

Obviously, Sean's robot is one of them. And yet the company did not warn him about the security flaws affecting his device. After I told Ecovacs about our experiment, a company representative said that an update for the X2 would be available in November 2024.

I became curious about who is responsible for ensuring that these internet-connected devices are truly secure. It turns out that there are no mandatory rules in Australia guaranteeing the impossibility of hacking smart devices. Last year, the Ministry of Home Affairs published a voluntary code of practice, compliance with which is "encouraged but not mandatory."

This means that companies producing devices for sale in Australia, including Ecovacs and other home robotics companies, are not required to test their products for protection against even the simplest vulnerabilities.

However, Ecovacs did test the X2 and received a security certificate from the German company TÜV Rheinland. The robot was tested for compliance with the cybersecurity standard with the catchy technical name ETSI EN 303 645, which is proposed to be partially adopted as part of Australia's Cybersecurity Strategy.

Most companies engaged in the production of home robotics, including Ecovacs, Xiaomi, iRobot, and Roborock, regularly certify their products according to this standard, and in many countries, this is a basic requirement. And this, according to Gis, is "the scariest part."

He found that Ecovacs devices are extremely vulnerable to hacking, despite being certified as safe. Gis discovered these security vulnerabilities by spending just a little free time. The same was done by Brelynn Ludtke and Chris Anderson, two other independent researchers. So why didn't the multinational company that was supposed to test it do so?

I contacted TÜV Rheinland to find out. In response to my questions about the testing processes, Alexander Schneider from TUV Rheinland directed me to a digital certificate that contained almost no information about how the testing was conducted.

"We are confident that our tests meet all aspects of the standard," Schneider said in a statement. Gis, in turn, claims that at least five of the 13 provisions of the standard were not met by Ecovacs X2 when he tested it.

According to Schneider, the vulnerabilities discovered by Gis were not examined during testing "because they fall into the realm of professional hacking attacks." He says that TUV Rheinland certification does not guarantee the prevention of cyberattacks by serious hackers. Well, who do they think usually carries out the hacking then?

Seeking a second opinion

Lim Yun Ji, a former cybersecurity tester at the competing certification company TÜV SÜD, has practical experience in certifying robot vacuum cleaners to the same standard. According to him, the testing process is largely "left to the interpretation" of the certifying companies.

He is confident that testers do not necessarily need to conduct "deep or professional attacks."

This position is explained by the fact that such products are brought to market very quickly. Although the standard indicates the need for general security features, there is no explicit requirement for their proper implementation. It all depends on the experience of the laboratory and the staff working with the device for cybersecurity testing.

Testing is often carried out before the product is released, while new, unforeseen cyber threats constantly arise.

The software running on smart devices needs to be regularly updated to keep up with the latest known issues. And each new version of the software uploaded to the robot can potentially introduce new vulnerabilities.

According to Lim, it would be impractical to conduct independent testing of each new version, as this process could take months to complete. But, of course, product labeling showing that devices meet certification standards can create a "false sense of security" for consumers.

A representative of the Australian Ministry of Internal Affairs stated that the government plans to introduce mandatory safety standards for smart devices, as well as measures to ensure their compliance, which "will prevent the sale of non-compliant devices in Australia." He did not comment on the effectiveness of the ETSI EN 303 645 standard, which was mentioned in the public consultation materials as a potential basis for adoption.

According to Dennis Gies, the most alarming aspect of a Bluetooth attack is how difficult it is to detect. "If you do everything very quietly, the victim will never know about it." The warning sound for video mode is not played. The robot vacuum cleaner continues to clean in normal mode. The hack leaves no traces on the device. Therefore, you will never know if any suspicious companies are using your photos for their nefarious purposes. And as it turned out, they do use them.

AI learns from stolen data

Photos, videos, and voice recordings made in customers' homes are used to train the company's artificial intelligence models.

The manufacturer stated that its users "willingly participate" in the product improvement program. When users agree to participate in this program through the Ecovacs smartphone app, they are not informed about what data will be collected, only that it "will help us improve the features and quality of the product."

Users are prompted to click "above" to read detailed information, but there is no link on this page.

The Ecovacs privacy policy, available elsewhere in the app, allows for full user data collection for research purposes, including:

2D or 3D map of the user's home created by the device

Voice recordings from the device's microphone

Photos or videos recorded by the device's camera

It also states that voice recordings, videos, and photos deleted through the app may still be stored and used by Ecovacs.

An Ecovacs representative confirmed that the company uses data collected as part of its product improvement program to train its artificial intelligence models. Critical cybersecurity vulnerabilities that allow some Ecovacs models to be hacked remotely cast doubt on the company's ability to protect this confidential information.

Even if the company does not act maliciously, it itself may fall victim to corporate espionage or actions by state actors. In a 2020 blog post, two engineers from Ecovacs Robotics' artificial intelligence department described the problem they faced as follows: "Creating a deep learning model without large amounts of data is like building a house without blueprints."

With publicly available datasets, there is a problem, they are simply not available, as the robot sees the environment "from the ground." Therefore, the company needed its own data collection.

A company representative said that this preliminary dataset does not contain "real household information of users." However, since the launch of the products, they have confirmed that the data of users who participated in the "Product Improvement Program" is used to train the artificial intelligence model.

"During data collection, we anonymize user information, ensuring that only anonymous data is uploaded to our servers," the representative said in a statement. "We have implemented strict access management protocols for viewing and using this anonymous user data."

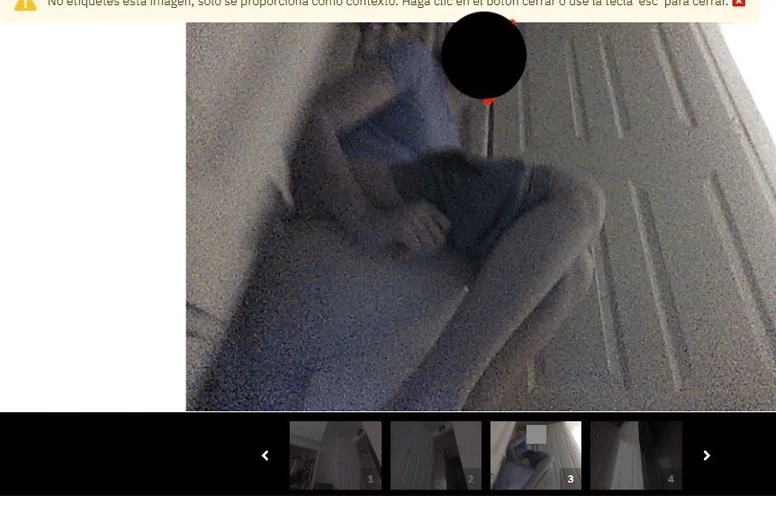

But in reality, images from robot vacuums have already leaked online. In 2022, intimate photos taken by iRobot devices, including the infamous photo of a person sitting on a toilet, were published on a "banned social network." In this case, the robots that took the pictures were part of a testing program in which users participated.

A company representative told MIT Tech Review that these are "special development robots with hardware and software modifications that have never been and will never be in consumer iRobot products available for purchase."

The devices were physically marked with bright green stickers (they said "video recording in progress"), and users consented to send data to iRobot for research purposes.

One thing is to allow a company based in the USA to access device images. But it's quite another when photos end up on a social networking site.

And here comes the question of how they got there.

The company iRobot has contracted with Scale AI, a company engaged in data for training artificial intelligence, to analyze raw footage to train an object detection algorithm.

According to Scale AI founder Alex Wang, his data processing system generates virtually all the data needed to run leading large language models. It sounds very serious, but in reality millions of workers work in conditions far from ideal.

Online data annotators often work in internet cafes. Workers label images so that AI can generate politicians and celebrities, edit text fragments so that language models like ChatGPT do not produce nonsense.

The company iRobot terminated its cooperation with Scale AI after its contractors posted photos on social networks.

Do cleaning robots even need high-definition cameras?

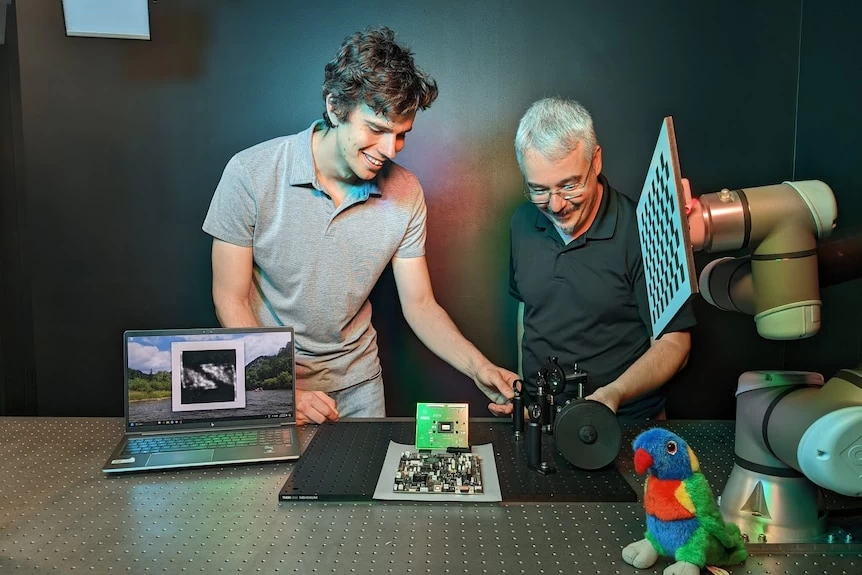

Researchers at the Australian Center for Robotics have developed a solution that can completely avoid this problem. To protect sensitive images from hackers, a technology has been developed that changes "the way the robot sees the world".

Essentially, it's a camera that initially "preserves privacy".

Since the image obtained with the camera is encrypted beyond recognition even before it is digitized, attackers cannot access the raw images. Nevertheless, the encrypted image still retains enough information for the robot to navigate in space. The technology is not yet ready for commercialization, but Dr. Dansereau is confident that technology companies will adopt it.

Thank you for your attention. Stay vigilant.

Write comment