- Security

- A

Two camps of C++

There are currently many debates and discussions about the future of C++.

Not only on Reddit and one orange website, but also certainly at official C++ standard committee meetings.

Absolute state (of the C++ language)

It seems we are in the following situation:

The C++ Evolution Working Group (EWG) has just reached a consensus on the adoption of P3466 R0 - (Re)affirm design principles for future C++ evolution:

This means no ABI breaks, maintaining layout compatibility with C code and previous versions of C++.

It also means no "viral annotations" (e.g., lifetime annotations)1.

Doubling efforts on many incompatible tasks, such as no ABI breaks and the zero overhead principle2.

Whether this is good or bad, it is (literally) doubling down on the current trajectory of C++ language development.

1. If being cynical, this can be interpreted as an explicit "disapproval" of Rust's lifetime annotations and Sean Baxter's Safe C++ proposal. If less cynical, it is at least a sober recognition of the fact that the industry does not want to refactor old code.

2. "We don't pay for what we don't use." Essentially, an old C++ feature can impact runtime performance only if you actively use it. This is not quite compatible with a stable ABI, because a stable ABI (understood as a C++ feature) precludes certain performance improvements.

Meanwhile:

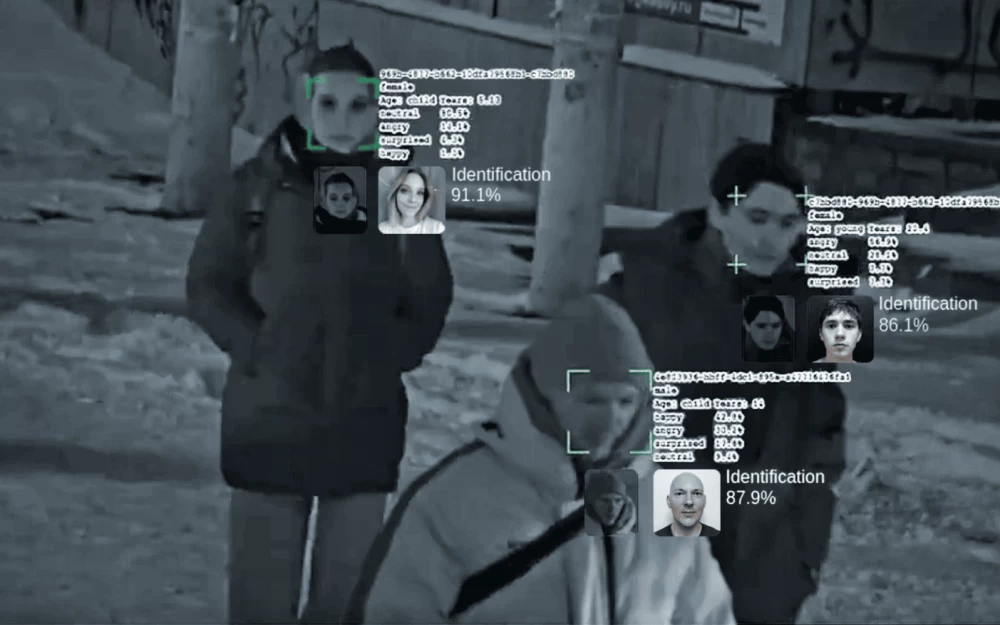

The US government wants people to stop using C++:

That's right: various branches of the US government have issued articles, reports, and recommendations to warn the industry about the undesirability of using memory-unsafe languages.

All sorts of major tech players are adopting Rust:

Microsoft is rewriting core libraries in Rust.

Google seems to have decided to switch to Rust and has started working on a tool to ensure bidirectional functional compatibility between C++ and Rust.

AWS uses Rust.

and so on.

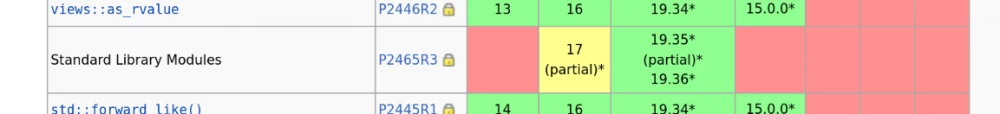

Speaking of big tech companies: have you noticed that Herb Sutter is leaving Microsoft, and MSVC seems to be slow to implement C++23 features and is asking the community to prioritize.

The infamous Prague ABI vote took place (in short: "C23 will not break ABI, and it is unclear if this will ever be done"). Google has reportedly significantly reduced its involvement in the C development process and instead started working on its own C++ successor language. The company even released a summary listing all the problems it encountered when trying to improve C++3.

There are already well-known stories in the community of people who tried their best to participate in the standard committee processes: they were just chewed up and spat out.

Modules are still not implemented. Are we modules yet?4

"Security Profiles" are still in a strange state and have no ready implementation; there are attempts to add a certain degree of security to already written C++ code with minimal changes to this code. Sean Baxter himself took a position against the profiles and said that C++ is "insufficiently covered by specifications".

3. I think Carbon is much more interesting than most people perceive it. Maybe I'll write a post about it someday.

4. We're getting there! It seems that just a few days before the article was published, GCC added support for the std module. This may take a long time, and who knows what the ecosystem will be like, but it's already progress!

I don't know about you, but if I were looking at all this as an outside observer, it would definitely seem to me that C++ is essentially falling apart, and that a large number of people have lost faith in the C++ committee's ability to somehow solve all these problems5.

5. Falling apart now? Well, it depends on what you mean. All this C++ code isn't going anywhere. So in that sense, no. The code in C++, at least, will continue to exist.

Two cultures

It seems people are looking for other solutions.

Let's take Google. This company has obviously lost faith in the "almighty process" since the ABI vote. This is not a loss of faith in the language itself, Google has one of the largest C++ codebases in the world, and it has served the company well. It is a loss of faith in the language's ability to evolve under increasing pressure from various sides (potential government regulations, competing languages, the need for major players to improve performance and security guarantees, and so on).

So what's the problem? Why doesn't C++ just... change?

Well, it's easy to understand. Just read what Herb Sutter wrote in his article on profiles:

«We must minimize the need to change existing code. Decades of experience have shown that most users with large codebases cannot and will not change even 1% of the lines of code to comply with strict rules, even for security reasons, unless forced to do so by government requirements,» — Herb Sutter

Cool. Did that surprise anyone? I don't think so.

For contrast, let's take Chandler Carruth's biography from the WG21 member page:

I led the design of tooling and automated refactoring systems for C++, built on Clang and later became part of the Clang project. […]

At Google, I led the project to scale Clang-based automated refactoring tools to the size of our entire codebase (over a hundred million lines of C++ code). We can analyze and apply refactorings to the entire codebase in just twenty minutes.

Notice anything? (Of course you did, I highlighted it on purpose.)

"Automated tooling." But it's not just limited to that, it's just one bright example.

Essentially, we see a conflict between two radically different camps of C++ users:

Relatively modern capable technology corporations, recognizing that their code is a valuable asset. (Here you can go beyond just big tech. Any sane C++ startup also falls into this category.)

Everyone else. Any ancient corporation where people are still arguing about how to indent code, and one young engineer is begging his management to let him set up a linter.

One of these groups will be able to handle the migration almost seamlessly, and it is the group that is able to create their own C++ stack based on versioned sources, not the group that still uses pre-built libraries from 1998.

This ability to create an entire stack of dependencies based on versioned sources (preferably with automated tests) is probably the most important dividing line between the two camps.

Of course, in practice, it is a gradient. I can only imagine how much sweat, blood, money, and effort it took to turn big tech companies' codebases from horrifying pieces of dirt into relatively manageable, buildable, slightly less frightening pieces of dirt with proper version control.

With hindsight, it's easy to think that all this was inevitable: that there is a clear division between the needs of corporations like Google (which use relatively modern C++, have automated tooling and testing, and modern infrastructure) and the desire (very strong) for backward compatibility.

If you look at it soberly, it turns out that the idea of a single, dialect-free, unified C++ seems to have been dead for many years6. We have at least two main varieties of C++:

Any even remotely modern C++. Anything that can be built from source with versioning using a special clean and unified build process that is at least slightly more complex than raw CMake, and that can at least be loosely called working. Add some static analyzers, a formatter, a linter. Any standard of ensuring the cleanliness and modernity of the codebase. Probably at least C++17, with

unique_ptr,constexpr, lambdas,optional, but that's not the point. The most important thing is the tooling.Legacy C++. Anything that is not the first point. Any C++ that is stored on ancient dusty servers of a mid-sized bank. Any C++ that depends on a terribly outdated piece of compiled code with lost sources. Any C++ that is deployed on a pet server; to deploy it somewhere else, it would take an engineer a whole month just to figure out all its indirect dependencies, configurations, and environment variables. Any codebase that is considered a cost center. Any code in which building any used binary from source requires more than pressing a few buttons, or is even impossible.

6. Whether it ever lived at all, with all these various compilers and their own extensions, is another question.

As you may have noticed, the main difference is not in C++ itself. The difference lies in the tooling and the ability to build from source with versioning in a clean, well-defined way. Ideally, even the ability to deploy code without having to remember that one flag or environment variable that the previous developer usually added to keep everything from breaking.

How well Google's codebase adheres to the idioms of "modern" C++ is secondary to the quality of the tooling and whether the code can be built from source.

Many will say that tooling is not the responsibility of the C++ standards committee, and they will be right. Tooling is not the responsibility of the C++ standards committee, because the committee disclaims any responsibility for it (it has focused its efforts on the specifications of the C++ language, and not on specific implementations)7. This is done deliberately, and it is hard to blame them, given the legacy baggage. C++ is a standard that unifies different implementations.

7. However, this is somewhat unfair. There is a research group SG15 that deals with tooling. See, for example, this post. Of course, the whole process is still focused on writing papers, and not, for example, on releasing a canonical package manager.

Nevertheless, if the Go language did something right, it is the emphasis on tools. Compared to it, C++ is in the prehistoric era, when linters were not yet invented. C++ does not have a unified build system, it has nothing even close to a unified package management system, it is incredibly difficult to parse and analyze (which terribly hinders tooling), and it fights a frighteningly unequal battle with Hyrum's law over every change that needs to be made.

There is a huge and growing chasm between the two camps (good tooling, seamless build from source vs. poor tooling and inability to build from source); frankly, I don't see any movement towards bridging this chasm in the foreseeable future.

The C++ committee is striving to maintain backward compatibility at all costs.

By the way, I'm not even particularly against this! Backward compatibility is very important to many people, and they have good reasons for it. But others don't particularly care. It doesn't matter which group is "right": their views are simply incompatible.

Consequences

That is why the situation with profiles is as follows: security profiles are not intended to solve the problems of modern, technologically advanced corporations writing in C++. They are needed for improvements without the need to make changes to old code.

The same situation is with modules. The user should be able to "simply" import the header file as a module, and there should be no problems with backward compatibility.

Of course, everyone likes features that can simply be added and that bring improvements without the need to change old code. But it is quite obvious that these features were designed primarily with "legacy C++" in mind. Therefore, any feature that requires migration from legacy C++ is not an option for the C++ committee, because, as Herb Sutter said, essentially, you can't expect people to migrate.

(Again, creating features with legacy C++ in mind is not a bad thing. This is a perfectly reasonable decision.)

This is what I try to keep in mind when reading articles on C++: there are two large audiences. One prefers modern C++, the other prefers legacy C++. These two camps have huge disagreements, and many articles are written with the needs of a specific group in mind.

Obviously, this leads to everyone talking about their own thing: whatever people think, in fact, security profiles and Safe C++ are trying to solve completely different problems for different audiences, not the same ones.

The C++ committee is making efforts to ensure that this gap does not widen. Presumably, that is why any moves towards Sean Baxter's Safe C++ are unacceptable to them. This is a radical change that can create a fundamentally new way of writing C++ code.

Of course, there is also the question of whether individual members of the C++ standard committee are simply extremely stubborn people clutching at straws to prevent an evolution they aesthetically disagree with.

I'm far from accusing anyone, but it's not the first time I've heard that the C++ committee uses double standards like: "To approve this proposal, we expect to see a fully working implementation for multiple working compilers, but we are happy to deal with individual large projects (e.g., modules and profiles) that do not have functional proof of concept implementation."

If this is true (I can't say for sure), then it is impossible to say how long C++ will continue down this path without a much more serious rift between the two camps.

And we haven't even touched on the huge pile of problems that broken ABI compatibility would cause.

Write comment