- Security

- A

Internet vs CAPTCHA: is there a future for tests like “find all pictures with bicycles”?

CAPTCHAs, which are supposed to “separate” humans from bots, have become a real headache for users. Sometimes you don’t just have to pick a traffic light or a “zebra crossing”, but solve complex puzzles or math problems, many of which can be baffling — while bots, it seems, crack them like nuts. At beeline cloud, we decided to dig into the topic.

Captcha… What on earth are you talking about?

Lately CAPTCHAs have been getting more and more unusual — even absurd. A striking example is a puzzle from LinkedIn. In it, users are asked to rotate a 3D model of a pink dog until it’s facing the direction indicated by a hand. Some security systems make users search for nonexistent objects: for example, clicking on traffic lights that aren’t in the picture, or marking bicycles hidden among pixelated noise. Two years ago, a CAPTCHA on Discord glitched and asked users to find in the given photos an item called “yoko” — something resembling a hybrid of a snail and a yo-yo toy.

Around the same time, a Hacker News regular shared that he encountered “the worst humanity test” in an app from one of the American streaming services. He was required to solve a math problem, but the CAPTCHA wouldn’t accept the correct answer: “I have a PhD in computer science, and if I can’t manage simple addition, trust me — the answers are wrong.” After failing, he chose an audio CAPTCHA, which offered several musical snippets and asked him to pick the one containing a repeating rhythmic pattern. Instead of clear patterns, however, the user heard cacophony and indistinct noise.

It feels like CAPTCHAs have turned into a sort of reverse Turing test: now machines are checking how far humans are willing to play by their rules. Unsurprisingly, such oddities have turned a tool for fighting bots into an object of jokes — with users deliberately creating hard-to-pass and funny challenges. For instance, early this year on Hacker News they discussed a CAPTCHA featuring the game Doom, in which you need to shoot three monsters armed only with a pistol — not an easy task for an inexperienced gamer: “This is a secret level (E1M9) that you can access after E1M3. Normally by this point the player already has a shotgun, a chaingun, a rocket launcher and probably armor. But starting this level with just one pistol — well, that’s something else.” Another example is ChessCaptcha, where you either have to place the chess pieces correctly (for beginners) or checkmate in one move (for advanced players) — the required mode can be chosen by the site owner.

Bot, you shall not pass! But maybe you will

Lately, in professional circles, the opinion is increasingly heard that classic CAPTCHAs — with traffic lights, motorcycles, buses, and all that — are no longer coping with their task. In this regard, a question arises, which in an interview with the British newspaper The Times was voiced by a professor from the University of California, Irvine: “Why do we still rely on a technology that nobody likes, is expensive, wastes people’s time, and is ineffective against bots?”.

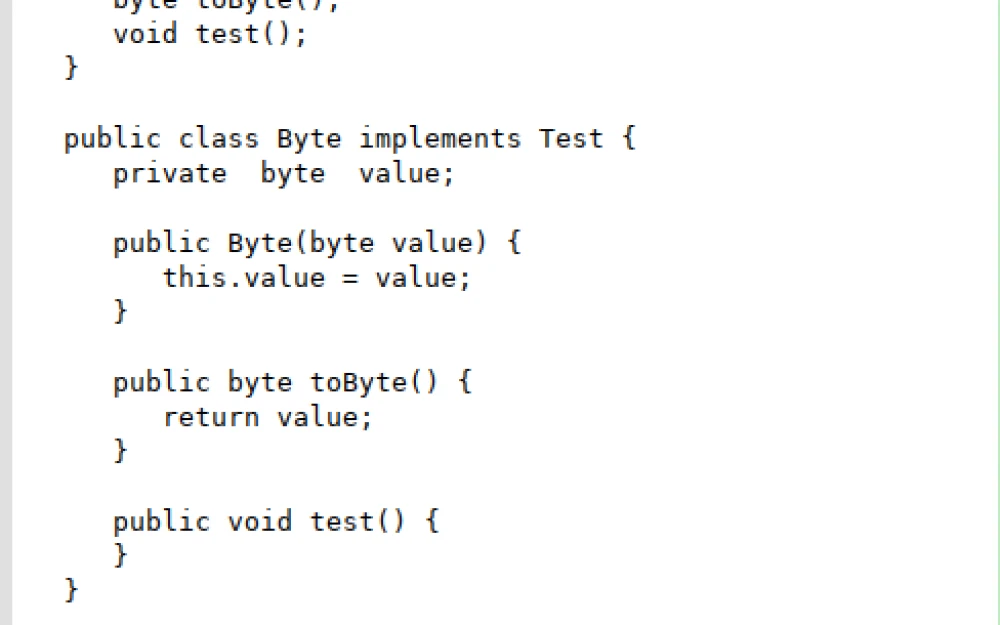

And a few more words about inefficiency. Back in 2016, specialists from Columbia University found several vulnerabilities in Google’s reCaptcha. They presented an exploit based on machine learning and image search that easily bypassed protection and solved 70% of CAPTCHAs within 19 seconds.

In 2023, their own research was conducted by specialists from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH), Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (USA), University of California, Irvine, and Microsoft. They asked 1,400 participants to solve ten different CAPTCHAs: graphical, text-based, interactive (with slider movement), and others — and then compared the results with bot performance data presented in specialized literature and colleague research. On average, people took up to 30 seconds to solve the test with an accuracy of up to 85%. Bots needed only 15 seconds, with accuracy ranging from 85% to 100% (depending on the task).

Last year, researchers from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich once again confirmed that tests like Google’s reCAPTCHA v2 cannot serve as reliable protection against advanced bots and scrapers. The authors of the study used the YOLOv8 model for image classification. The system easily recognized stairs, motorcycles, and pedestrian crossings — and to make it resemble a “real user” more closely, they modeled the cursor movement trajectory using Bézier curves.

Can a robot write a symphony? Or new ways to identify humans

Perhaps everyone has encountered behavioral CAPTCHAs (such as reCAPTCHA v3 from Google), which do not ask you to click on images, but instead analyze the user's actions in the browser. However, such systems are imperfect, and experts are increasingly pointing out that these behavioral tests may violate privacy. For example, in July 2020, the French National Commission on Informatics and Liberties (CNIL) ruled that the aforementioned reCAPTCHA v3 may not comply with GDPR, collecting data without user consent. Additionally, configuring sensitivity thresholds in such systems is a non-trivial task. Too strict rules lead to blocking legitimate users, while weak ones let bots through.

In an attempt to find an alternative solution, some suggest focusing on biometric methods of user identification, which may be more robust than behavioral tests. For example, a major Western service provider developed a cryptographic identity verification mechanism — CAP. It uses FaceID, TouchID on iPhones, and Android biometrics to gain access to the site. Data is stored locally in modules (TEE/TPM) on devices and is not sent to servers.

On the other hand, back in 2018, cybersecurity researcher Meriem Guerar from the Mohamed Boudiaf University of Science and Technology in Oran (Algeria), together with colleagues from the University of Genoa and the University of Padua in Italy, proposed implementing a series of simple physical checks for user identification. The method was named CAPCCHA — an abbreviation that stands for Completely Automated Public Physical test to tell Computer and Humans Apart. Specifically, it involves the need to tilt the device at a certain angle after entering a PIN code. However, such a "humanity check" is obviously suitable only for mobile devices with accelerometers and gyroscopes (mostly smartphones and tablets) and may be inconvenient for the elderly and people with physical disabilities.

New methods of user identification based on blockchain are also being developed — for example, World and Humanity Protocol. They offer decentralized identification to protect against Sybil attacks. The World project, launched in 2019 by Sam Altman, Alex Blania, and Max Novendstern, uses a special device — Orb — to scan the eye's iris. The collected data is converted into a cryptographic hash using zero-knowledge proofs (ZKP) and placed on the blockchain. As for Humanity Protocol, launched in 2023 by entrepreneur Terence Kwok, it suggests scanning the palm instead of the iris.

It is assumed that applications supporting these protocols will check the hash in the blockchain to confirm that the user is not a bot. To date, both projects have attracted an audience of several million people. However, despite this, their prospects are assessed ambiguously. In particular, critics believe that scanning the palm or iris still carries the risk of data leakage, and the process itself requires specialized equipment (or at least a quality camera), which limits the potential audience and applicability.

Bots also need the internet

There is an opinion that in the coming years, AI agents will become the main way of interacting with websites, applications, and services. They are already capable of autonomously performing actions on behalf of users — from making purchases to filling out forms. For example, such an agent is currently being created by Walmart. The assistant will be able to perform routine tasks, such as reordering products and creating shopping lists based on specific criteria. In the future, Walmart plans to implement interaction protocols with agents from other companies. In particular, OpenAI is currently working on a similar project — their agent can also make purchases and search for products online.

The development of this trend turns the concept of CAPTCHA on its head — because they were developed to counter robots, but now robots are becoming “active internet users.” If AI agents become firmly embedded in our lives, CAPTCHAs will need to identify not humans, but “correct” bots — those that can work with websites or applications on behalf of ordinary users. The report from the Center for Security and Emerging Technologies (CSET) at Georgetown University proposed embedding digital certificates or tokens with the identification data of the "owner" in such AI agents to confirm their legitimacy.

However, a potential problem here is certificate forgery. There is also an open question about data privacy and responsibility for the actions of robots. CSET proposed enhancing the protection of tokens and certificates with encryption, minimizing data collection, and implementing real-time monitoring to detect suspicious AI system activities, such as unauthorized transactions.

So future verification systems will need to take into account the growing number of AI agents in order to maintain a balance between security, privacy, and convenience. Developing protocols for legitimate agents may become the next step in the evolution of CAPTCHA. Work on tools to assess such intelligent systems is already underway. This year, a team of engineers, including specialists from the MBZUAI University of Artificial Intelligence in the UAE, introduced the Open CaptchaWorld benchmark. It includes 20 modern types of CAPTCHAs (a total of 225 individual tasks) and offers a new evaluation criterion — CAPTCHA Reasoning Depth, which shows how many steps a system needs to solve a particular puzzle. The engineers released their benchmark as open source (under the MIT license) and hope it will contribute to the development of verification systems.

Beeline Cloud — secure cloud provider. We develop cloud solutions so you can deliver the best services to your clients.

What else we have on our blog:

Pelicans, sarcasm, and games — fun LLM benchmarks

How neural networks can stop fearing and learn to love “synthetics”

A pill against phishing

Write comment