- AI

- A

Will AI Really Replace Programmers in 12 Months?

The Human Factor That Everyone Overlooks

When Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, said that we are just 6-12 months away from AI systems capable of doing everything programmers do, I had to stop.

This is not "in the future." This is practically next year.

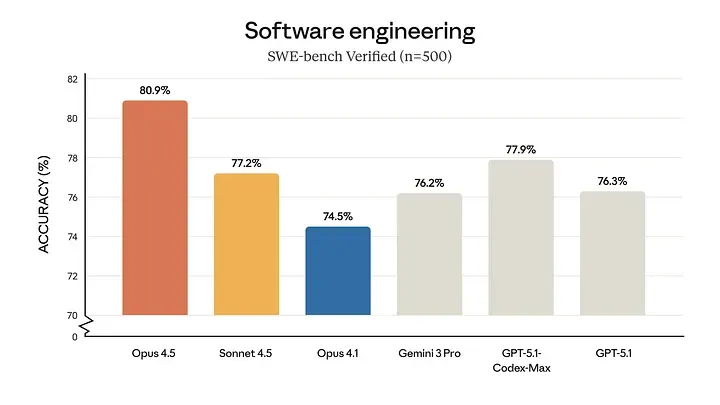

At the same time, Anthropic introduced performance tests for its new model Claude Opus 4.5, showing significant improvements in coding, reasoning, and handling complex tasks. The numbers look really impressive.

And I began to wonder: do these tests really mean that software development will soon be fully automated? Let me break down what I think is actually happening.

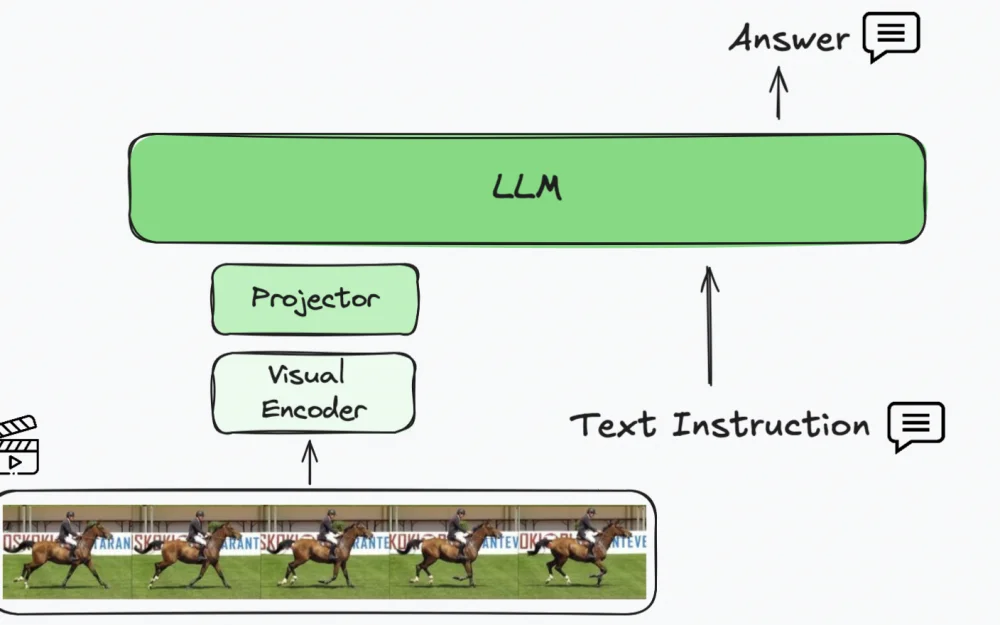

What these benchmarks are really testing

According to Anthropic, Claude Opus 4.5 performs much better than previous versions in software development tests like SWE-bench, long tasks requiring multiple steps, complex reasoning, and effective use of various tools.

You can also check out the blog from Anthropic for more details.

They also claim that the model maintains focus better during extended workflows. This is really important because earlier AI models were decent at writing individual snippets of code but terrible at remembering context over several steps.

If this gap is narrowing, the potential for automation is definitely increasing.

But here’s what worries me. Benchmarks like SWE-bench test whether a model can solve clearly defined problems in controlled environments, usually with feedback from tests guiding it.

This is completely different from the chaotic reality of actual software development work. Real projects have vague business requirements that change every week. Documentation that is either missing or outdated. Third-party APIs that break without warning. Deployment pipelines held together with tape. And stakeholders who all want different things.

Benchmarks measure technical skills in a vacuum. They do not measure your ability to navigate organizational chaos.

What I see in real developer work

I’ve observed how people actually use these AI tools for coding day in and day out, and the pattern is quite clear.

Yes, AI can now generate complete working programs. I’ve seen developers deploy fully functional applications in hours that used to take days. But here’s what they keep saying: writing code was never the hard part.

The hard part is figuring out what to build, dealing with changing requirements, managing technical debt, maintaining legacy systems, and working with people who have conflicting priorities.

I’ve also noticed specific patterns of failure. AI fixes bug A, which breaks function B. Then it fixes B, which breaks A again. This cycle continues until someone intervenes manually. AI optimizes each part in isolation but cannot see how everything is interconnected.

Another thing I constantly encounter is over-engineering. AI tools build overly complex solutions because they do not question the original approach. They simply implement what you ask for. They do not object or say, “Wait, is this really the best way to do this?”

The pattern I see most often: AI writes code quickly. People are still deciding what code should exist.

The productivity gain is real, but so are the limitations

To be honest, AI is already handling a ton of implementation work. For standard CRUD operations, frameworks, and basic integrations, the productivity boost is undeniable. I’m getting more done faster in these areas.

But when I work on complex distributed systems, security-critical code, or data integrity issues, my confidence in AI drops significantly.

I recently spent a week tracking down a subtle contextual mismatch that caused cascading failures in several services. An AI would not have caught this. At another time, I realized that explaining my entire system architecture to the AI in sufficient detail to generate correct code would take longer than just writing it myself.

What’s happening is not the elimination of work. It’s a transformation of work. I am shifting from writing code to reviewing and editing code. This still requires a deep understanding.

And here’s what concerns me: if we replace junior engineers with AI, who will become the senior engineers in five years? You can’t learn to review code well if you’ve never built systems yourself. Understanding comes through action.

There’s also the question of accountability. AI can generate outputs but cannot own the consequences. When production breaks at 3 a.m., someone still has to explain what happened, fix it quickly, and prevent it from happening again.

Engineering is not just about implementation. It’s about ownership.

Why these forecasts may be overly optimistic

Let’s talk about the business side for a second.

AI companies are actively competing for corporate clients and investor dollars. Claims of radical job replacement create urgency. They push companies to quickly restructure workflows around AI tools before their competitors do.

I think aggressive statements about automation may also be related to shaping the market and expectations, even if full automation doesn’t arrive on schedule.

Don’t get me wrong. Technology is improving at an incredible pace. But business incentives reward optimistic timelines over realistic ones.

There often exists a significant gap between where technology is headed and how quickly it is actually deployed in real companies with real constraints.

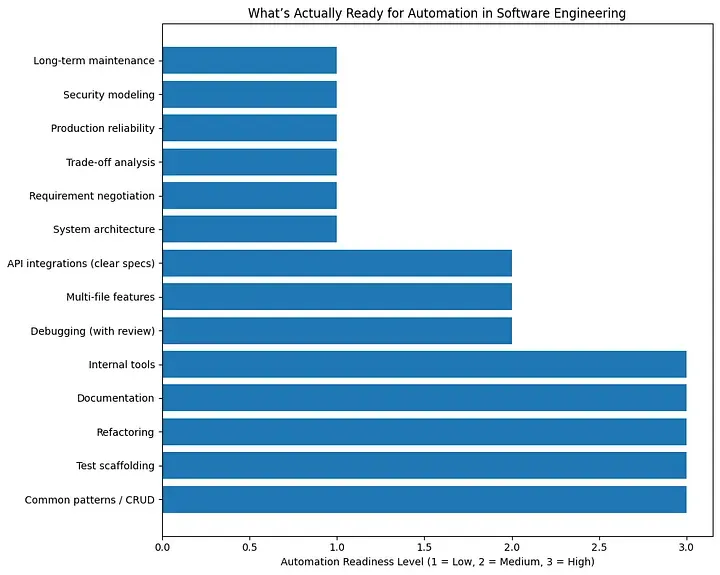

What is actually ready for automation (and what is not)

Based on what I’m experiencing and observing, here’s my breakdown:

Ready for high automation now:

Code for common patterns

Test frameworks

Refactoring existing code

Documentation

Internal tools

Possibly halfway there:

Debugging with human oversight

Multi-file functions

API integrations when specifications are crystal clear

Not even close:

Decisions on system architecture

Negotiations on requirements

Analysis of trade-offs

Decisions on production reliability

Security modeling

Long-term maintenance strategy

Implementation is becoming dramatically faster. But decision-making under uncertainty doesn’t go away.

This explains what I see around me. Engineers are more productive, but no less important.

How to properly use AI in development — right now

This whole discussion about what AI can and cannot do raises an important practical question: how can developers effectively use these tools today?

The problem isn’t that the technology is underdeveloped. The problem is that access to modern models is often hindered - expensive subscriptions, complicated APIs, token limitations.

But AI for development has already become cloud-based. You no longer need a local installation or a corporate subscription to GitHub Copilot for $20/month.

Services like BotHub provide access to the same Claude Opus 4.5 models we’re talking about directly from your browser.

No VPN is required for access, you can use a Russian card.

You can get 300,000 free tokens through the link for your first tasks and start working with neural networks right now!

Real work has never been just a set of text

Here’s what I’ve realized: the most challenging part of software development has always been deciding what to build and why.

Code is just the visible outcome of that decision. Engineering is the invisible thought process that shapes it.

AI is getting really good at "how." It’s nowhere near mastering "why."

And here is the key point: incorrect "why" decisions become more expensive as systems grow. Faster implementation means that mistakes also spread more quickly.

Ironically, this can make strong architectural judgment more valuable, not less.

What "end-to-end automation" really means

Let me break this down into two scenarios.

If "end-to-end" means "AI can generate working code when given the right, detailed specification," then yes, we are quite close to that already.

If "end-to-end" means "AI can figure out the right specifications, resolve conflicts between stakeholders, manage evolving requirements, and remain accountable for system outcomes," then no, we are not even close at all.

The first is a technical implementation problem. The second is an organizational and cognitive problem.

Benchmarks primarily measure the first.

My forecast for the next year

Here’s what I think will actually happen over the next 12 months:

We will see fewer purely implementation junior roles. There will be more demand for engineers who can clearly define problems and make good architectural decisions. Agent-based coding tools will become standard. Prototyping and iteration will become much faster.

But we will also see a continuing need for human ownership of systems. A strong reliance on senior engineers for validation and decision-making. And many failures as companies push automation in poorly specified areas.

Software development will feel quite different a year from now. But I don’t think the role itself disappears.

Conclusions

Benchmarks for Claude Opus 4.5 show real progress. AI systems are indeed getting better at resilient reasoning and structured code generation.

But engineering is not just about producing code. It’s about making decisions under uncertainty, accountability for outcomes, and managing systems over years or decades.

Tools are changing rapidly. The nature of our work is shifting to higher levels of abstraction. But the role itself does not disappear on a yearly timeline.

I think the predictions of full automation confuse the growth of capabilities with actual replacement in organizations.

And if history teaches us anything, these two things rarely move at the same speed.

What do you think? Are we really 12 months away from AI replacing programmers, or is this just another exaggerated timeline? I would love to hear your perspective in the comments.

Write comment