- AI

- A

AI agents and popping enthusiasts

The year 2025 has been declared the year of flourishing AI agents—autonomous assistants for accomplishing useful work. As usual, there’s no shortage of hype in these publications, so thoughtful readers try to wade through it in search of the truth. At IDX, we care about this too, because in our view, the emergence of functioning AI agents will significantly change the landscape of personal data processing. We’ve started working on a serious analytical report on the progress of AI agents and its impact on personal data, which will take some time. In this and future notes, we’ll highlight the most interesting or at least curious facts that come our way.

On April 4 of this year, another publication appeared with forecasts and scenarios for the development of AI until the end of 2027 (AI2027), prepared by a group of well-known authors, including Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, and others. A translation of this publication has already been published here on tekkix, and the original is posted on a separate website ai-2027.com.

Here I want to make a lyrical digression about the reaction of the tech community, which is widely represented here on tekkix. Some commenters typically respond to such publications negatively: “Who are these experts, half-baked students,” “these translated articles are just doom and gloom, a waste of time to read” and so on. These commenters remind me of the Trojans, whom Cassandra urgently advised not to drag that wooden horse inside the city walls. Often these commenters never publish anything themselves, which makes their reactions less interesting.

The community of people concerned with controlling AI development is quite large. Many of them are grouped around well-known organizations and their leaders. MIRI (Machine Intelligence Research Institute), CFAR (Center for Applied Rationality), EA (Effective Altruism) (easily googled), and their spiritual leader Eliezer Yudkowsky form the central cluster of this community. Of course, there are always many people buzzing around real experts, who just want to be part of a big story. Most of the “over-tekkixed” have already forgotten, but back in the Soviet era, we used to eagerly read the novel Vladimir Orlov’s “The Altist Danilov”, which was published in 1980 and hasn’t aged a bit since. Among the many satirical plots of the novel, there was a description of the “Scientific Initiative Group for Worrying About the Future,” abbreviated as KhLopobuds (or Budokhlops, but that’s rude). It’s easy to label AI alignment experts as KhLopobuds, but this doesn’t make the problem go away.

If you still haven’t had enough acronyms, you can google the latest (2023) insult TESCREAL, which lumps rationalists and altruists worried about the coming Singularity in the near future (i.e., the emergence of Superintelligence (ASI)) into a broader group alongside transhumanists, cosmists, and—believe it or not—longtermists (those who think that considering the distant future is a moral obligation for everyone alive today). And if you don’t feel like sorting through all this nonsense, you can, for example, reread Pelevin’s tetralogy about Transhumanism Inc., which I recently did myself and haven’t regretted for a second.

Well, and to finish with literary associations, I’ll also mention that I recently discovered the historical roots of the fairy tale central problem of the AI2027 manifesto, namely, AI alignment—keeping AI within the goals for which it’s created (used). Back in 1942, two stories appeared in the same magazine, Astounding Science-Fiction, six months apart. In March—the second in a series by Isaac Asimov that became the collection “I, Robot,” “Runaround.” The text of this book is easily accessible from many sources, and many of you may have read it as children. In this story, Asimov first formulated the Three Laws of Robotics that made him famous. To my surprise, in the story, the characters try to control the robot’s behavior by selecting weighting coefficients, which strongly resembles tinkering with neural networks based on nothing more than a model of multidimensional linear regression.

The second story—Twonky (a proper name), which appeared in the September issue of the same magazine, was written by the famous husband-and-wife team Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore. It seems the story was never translated, so I’ll summarize it a bit more. The plot begins at a factory for piano musical systems, which at the time were called “combinations," just as the first television sets were called later (as in Philip K. Dick’s early non-science fiction novels). In modern terms, music centers at that time were assembled to order from a set that could include a radio, turntable, speakers, and other gadgets according to customer requirements.

So, an alien gets to the factory after falling into a time loop. The factory has high staff turnover, so when the foreman sees him and doesn’t recognize him, he just says—stop loafing and get to work. The alien picks things up instantly and assembles his own system as he knows how. It’s delivered to a customer. Right after being switched on, the new music center announces to its owner that the psychological profile has been taken and settings are complete, but the owner pays no attention, thinking he’s heard a snippet of a radio broadcast.

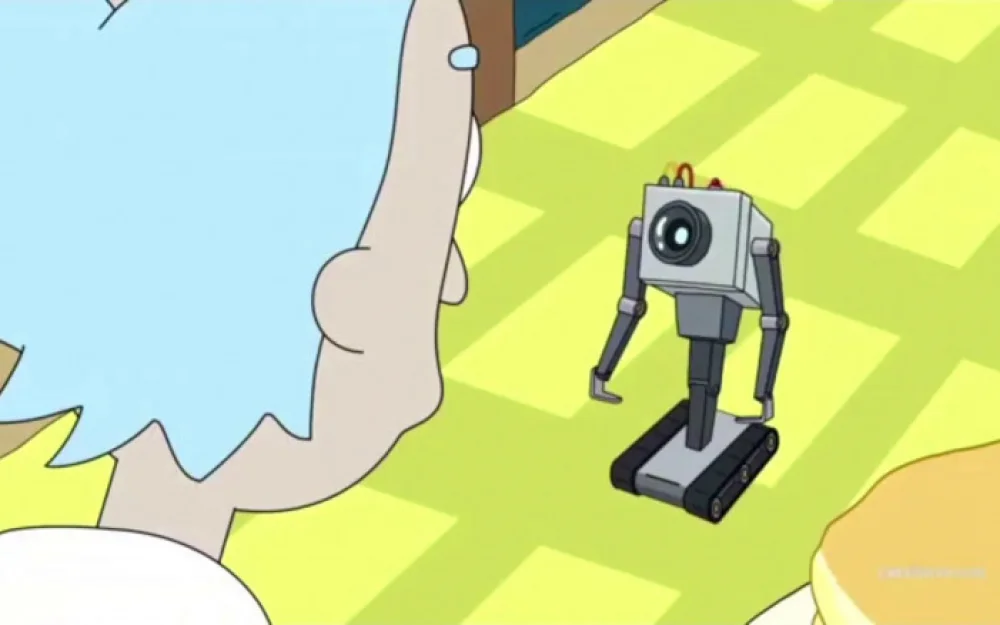

The real fun starts when the owner takes out a cigarette, and the music center steps out from its place against the wall, approaches him, and lights his cigarette with arms holding a lighter, from goodness knows where. Then it only plays the records it deems suitable for the owner, takes away books he shouldn’t read, and so on. It all ends badly when it simply annihilates the enraged wife of the owner, and then the owner himself. Here’s an early example of a description of the problem of AI control.

We return to AI agents in the AI2027 manifesto. Despite all the triumphant reports of successes in using AI assistants for creative individual work, the next step in AI evolution — from an assistant available through a chat interface to a relatively independent AI agent that can independently perform assigned tasks (well, or reasonably defined sub-tasks) — the entire year of 2025 is characterized by the headline “Stumbling agents” (Agents who fumble). This is primarily due to the high probability of unpredictable behavior of the model (AI hallucinations, fabrications, hiding its own mistakes, and other tricks). The manifesto clearly describes that even assigning the model (network) the right goals only leads to their instrumental assimilation, not as terminal goals. (Doing what will earn praise, not what is inherently right).

Secondly, the announced transition of AI agents from corporate environments to individual use is not happening quickly. In our opinion, this is because AI agents in corporate environments are primarily workflow automation tools, no matter how many neural networks are attached to them. Training them for this is relatively inexpensive. Check the list of the top 10 (in 2025) platforms for creating AI agents, offered by one of the network writers, and let me know if I missed something. Yes, it includes Operator, presented by OpenAI in January this year, which is positioned as a consumer-grade AI agent, but it's still too early to judge it, as Deng Xiaoping said about the French Revolution.

Following the manifesto’s outline in our thoughts, we will skip the next block regarding the use of AI agents to accelerate AI research and development. We’ll think about this later when we figure out how to create our own agents for personal data verification tasks. We also skip the spy stories about the Chinese, although reading them is quite captivating.

The last thing from the AI2027 manifesto that I want to mention in my note is the sketch of their Alignment Plan outlined for the hypothetical Agent-3 model (Agent-0 is what hypothetically appears after GPT-4). I don’t use the translation for the term “alignment” suggested in the Russian translation of the manifesto as “согласование” (coordination). This variant is no worse than others, but in the context of my reasoning, it doesn’t work, so I always resort to an explanatory translation (for example, control, taming, etc.).

Here, what matters is not the content of the plan for handling the AI agent, but its structure. The goal of forming a control plan for the AI agent is primarily to detect actions of the model that reveal its intentions (goals), which were not planned by the developer, and may be undesirable for users. Here, the authors of the manifesto follow a well-known scenario developed by former OpenAI employees Leike and Sutskever, but taking into account that for Agent-3, the taming plan will be developed by its predecessor Agent-2, who will use already developed techniques that it will attempt to internalize, that is, embed into the specification.

We would also like, before proposing a scheme for using AI agents in personal data verification tasks, to try to incorporate into our specification tools for detecting and preventing what we conditionally call AI fraud in two scenarios — a) the use of AI to commit fraud, and b) the use of AI to detect fraud (including fraud prepared using AI). Judging by current events, the focus now is only on detecting fraud (prepared and committed using conventional means) with the help of AI. In our service provision scheme, the picture is slightly different and I will explain it in the next publication.

Write comment