- Hardware

- A

Server Russian Roulette: What Risks Businesses Face by Trusting Stickers on Parts

In one of my previous articles, I wrote that after vendors left, for many companies, purchasing spare parts turned into a lottery.

Even for us — an IT integrator — the current situation often created unexpected problems. However, time has passed, and we have established new approaches to the procurement and verification of spare parts, learning to filter out counterfeits before they enter the customer's infrastructure. My colleague and I will share our experience on this.

My name is Ivan Zvonilkin, I am the head of the service project support group at the K2Tech comprehensive service expertise center. Together with my colleague Danila Fokhtin, a quality control engineer for spare parts, in this article, we will explain what risks companies face when purchasing spare parts today and how we deal with these risks.

Market Situation: Evolution of Problems

Defects have occurred before, especially among used components or discontinued equipment. But while non-original parts and outright counterfeits used to be rare, they are now encountered regularly. This significantly affects the continuity of all IT systems when a spare part does not “take off” immediately or fails within days or weeks. The IT director plans an upgrade for a specific maintenance window, deadlines are missed, and engineers spend valuable man-hours instead of working to determine the causes. But missing deadlines is only half the trouble. Much more dangerous is that with “gray” imports come problems that are extremely difficult to diagnose.

Risk #1. Difficulty in Diagnosis and “Phantom” Errors

The most dangerous thing about non-original spare parts is the hidden defects. When you buy a "cat in a bag," the cost of owning the equipment increases due to the time spent on finding and fixing errors.

This is well illustrated by an example from our practice: an EMC Unity storage system had a memory module failing on one controller. The system works, but it alerts "replace." The customer receives a replacement, plans a maintenance window, and removes the load. Then they install the new module — the system does not boot.

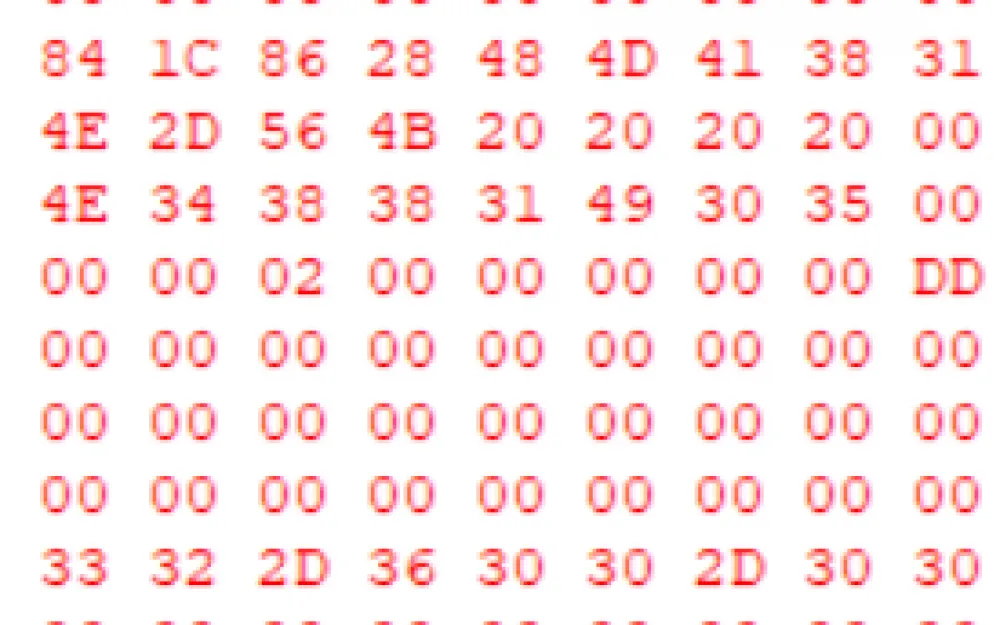

It turns out that the memory is non-original. But visually, this cannot be determined — faking the sticker costs pennies, but the storage system checks for the part number embedded in the SPD chip on the module. (And now we can read the dump directly from the SPD with a programmer to check all the necessary parameters.)

As a result, the replacement was unsuccessful, and the time allocated for maintenance (replacement + rebooting the controller ~40 minutes) is running out. The customer puts back the original "faulty" module, but Unity is quite "picky" about modules, and the controller doesn't start right away. It took several attempts to reseat other modules as well.

In the end, instead of the planned hour, much more time was spent + nerves and risks. Moreover, the next delivered replacement module could have the same issue. There is also a risk that with the "faulty" module, the controller might not even start at all, and there are no options to run it with reduced cache size either since the storage would then operate on a single controller without fault tolerance. If the second fails, the data becomes unavailable.

In our case, it was an unpleasant but manageable situation: there are backup storage systems and replication/backups. But imagine how this scenario looks in a company without such a safety net.

Here, an attempt to save a conditional 20-30% on gray components turns into a management nightmare for the IT director and infrastructure support teams. At best, a lot of time is wasted on endless resending and returns of defects. At worst, it leads to prolonged downtime of critically important services, the cost of which can far exceed the price of all the equipment.

Risk #2. Incompatibility

Incompatibility of components is a very insidious problem. The situation is so complex that we sometimes have to consult suppliers who themselves do not understand why their "originals" do not work. By the way, we are not the only ones facing such cases; other service teams in our center of expertise that support telecom solutions, engineering, and multimedia systems encounter them as well.

Here are just a few examples from our collection of computing hardware components:

Regional Features

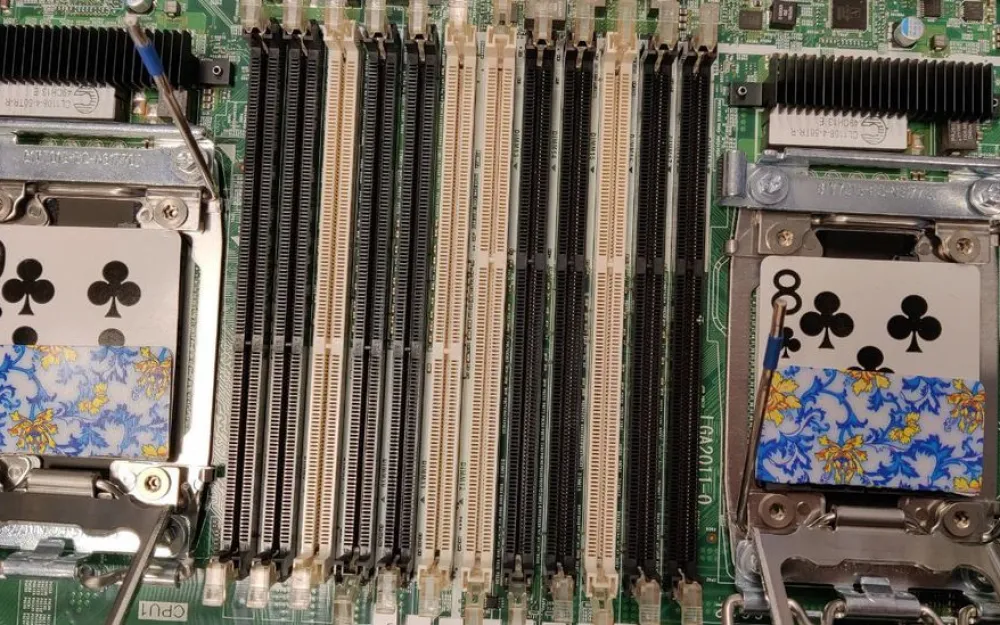

Take, for example, dual-socket servers. They are installed with a pair of identical processors, and if one of them fails, an identical model is required. Once, we ordered a discontinued Intel Xeon Scalable 6230R processor and were quite surprised upon receipt to see something resembling it, but with different markings. We installed the received "something" alongside the Intel — the server predictably did not boot, but if we left only it, everything worked.

We started digging and found out that there are some adapted ("import-substituted") "copies" of Intel processors from Montage Technology on the Chinese market. In fact, it is the same processor, but its CPUID/Spec Code differs from the original, so they will not work together. This once again showed us the importance of incoming verification: if a service engineer encountered such a surprise on-site, it would require a second trip or waiting for urgent delivery from the warehouse.

Conflicting Components

Sometimes, the client purchases a server themselves, and then its components conflict with our spare parts.

Recent case: we needed to replace an Intel Xeon Gold processor with a non-working NVMe line. We installed the original processor of the same model — the pair didn't work. We investigated. It turned out there was a mismatch in the steppings (which visually is not apparent on the processor, only visible through CPUID in the server logs). The server, apparently, was imported empty for cost-saving reasons and then filled with processors and memory that were found cheaper. They could have ended up with engineering samples or batches with non-standard steppings. In the end, we had to replace both at once.

Such problems were relevant at the dawn of the server era, and now they have returned. Now we have to keep at least a couple of processors on hand, ideally four, to cover the risks of incompatibility.

Just a forgery

In old HPE EVA storage systems, lead-acid batteries are used. They no longer make new ones, so they take refurbished ones for replacement. Once we opened one and saw something wonderful: part of the elements inside was soldered to the main board with only one contact, while the second was bitten off to the root. This means that the dead modules were left in the casing just for weight, to make the battery seem heavy and real: the supplier replaced only part of the elements, as they are connected in parallel, hoping we wouldn't notice, and everything would work. But it didn’t work out.

And the "vengeful" vendor lock

Sometimes clients come to us for help when their attempt at a self-upgrade has already led to disaster. For a long time, we didn't have dramatic cases, but just recently we received a perfect (in the bad sense of the word) example of how a delayed-action mine works.

The client bought 10 disks for an old Hitachi storage system (EOS) from a third party. Initially, everything went smoothly: the disks were added, and data was migrated to them. But after a few days, a "disk avalanche" began: the drives started failing one after another until the spare disks ran out and the RAID groups collapsed.

In theory, the client's backups would have saved them. In practice, the hardware itself was the issue preventing recovery. Due to a mass "death" of the disks, the storage system went into a deep state of confusion, and protective locking was activated. Normally, this can be removed either with vendor codes or by completely reinstalling the system. And here we hit a dead end. The vendor had obviously left and took support with them, and reinstalling the OS wipes out all licenses for features like tiering and snapshots. Keys, of course, were not stored—it's old equipment. It created a vicious circle: the hardware and backups exist, but the storage system turned into a brick. The only official repair method is reinitialization, after which the array becomes useless for current tasks due to lack of licenses.

Fortunately, our technical expertise in Hitachi architecture allows us to solve such problems. Since the client officially purchased this functionality along with the storage system, we were able to correctly restore the license configuration using engineering access and knowledge of the internal logic of the operating system.

In the best traditions of the genre, the work took place at night. While the entire country (and our colleagues) were enjoying the New Year's corporate party, an engineer, a licensing specialist, and an escalation team were working on-site. By morning, the storage system came back to life, and data began to be restored from backups. Now the client will deal with their disk supplier, and we may receive these "wonder-drives" for study.

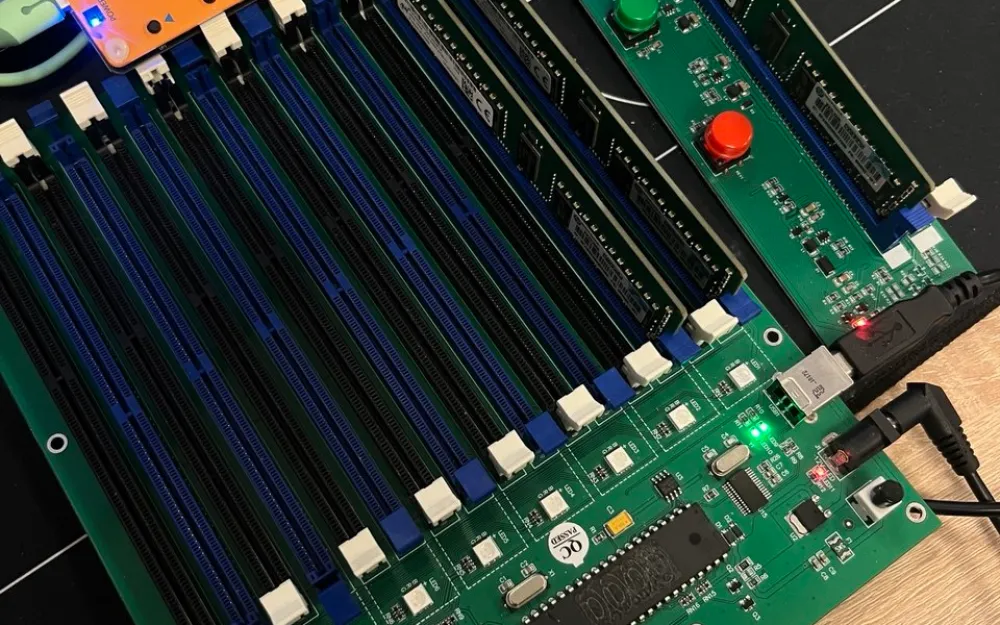

This case proved to us: the standard SMART test of a disk is no longer a guarantee. Counterfeit products have learned to deceive quick tests. Therefore, now we put suspicious batches under real load on the test benches.

"Customs" for hardware: our verification system

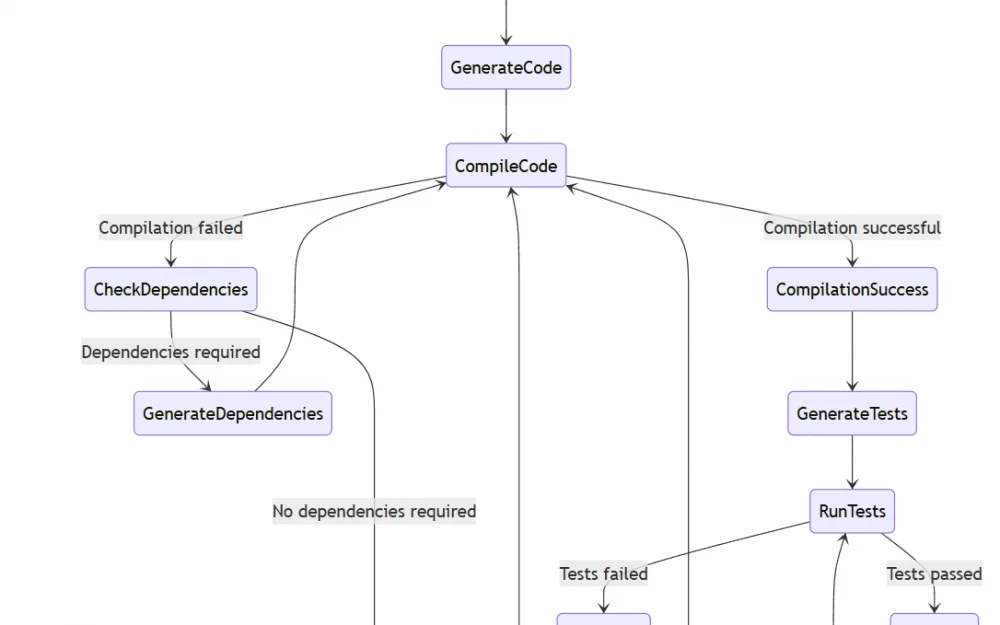

Last year, when we created the expertise center for comprehensive service, we reviewed and improved the procurement logic once again. We established our own ZIP verification system.

Of course, in theory, such incoming control can be organized within the client company, but in practice, it would require too much investment. To conduct quality checks, it would be necessary to maintain, power, and cool dozens of additional test benches, purchase special equipment, and allocate qualified engineers.

The second non-obvious problem concerns the independent procurement of spare parts: it creates enormous risks for the business, as there is too much unverified equipment on the market with a murky history of origin. Therefore, to avoid turning support into an endless troubleshooting of compatibility issues, it is critically important to carefully choose the contractor and understand who is bringing the parts and from where.

When foreign suppliers were still in Russia, incoming inspection was the responsibility of our warehouse staff. Now, this is handled by a separate division within our service contract support group — engineers who do not visit clients and do not repair servers in the field, but only deal with spare parts (inventory replenishment, testing, repairing the components themselves, etc.). We have divided the expertise since the primary task of field engineers is to prevent incidents and promptly eliminate their consequences, while warehouse staff cannot fully test the delivered part.

The main difficulty in this matter is the large scale. We have hundreds of models of equipment under service support, and it is physically and economically impossible to maintain a complete copy of the infrastructure of all clients with dozens of racks, power supply, and cooling in the office. We had to look for other ways to confirm the authenticity and functionality of the components.

Stage 1. Preparation

We began systematically collecting information about the characteristic signs of counterfeiting and set up specialized stands for thorough checking of equipment. We purchased test equipment and programmers, and wrote basic regulations. We built the inspection system iteratively: when we encountered a new type of counterfeit, we added a case to the knowledge base and updated the checklist so that the next engineer would know where to look.

This year, counterfeit sellers seem to finally have acquired quality printers. Their stickers and holograms are difficult to distinguish from the original; you have to closely examine the boards. The papers show that a 2-rank memory arrived with the correct capacity (according to the sticker), but upon closer inspection, the chips are soldered as if for 4-rank.

Stage 2. Visual Screening in the Warehouse

We teach warehouse workers not just to match the numbers on labels, but also to notice chips, cracks, strange stickers, and suspicious dirt. Sometimes we compare the part with reference photos from the internet.

An example of supplier creativity on the verge of absurdity. Recently, a customer invited us to check a shipment of new Dell servers purchased independently. The plastic frames for the fans raised suspicion due to differing colors. One of our engineers took this frame in hand, and it simply fell apart.

Nowadays, it's trendy to fill an empty Dell chassis with equipment based on the principle of "a thread from the world." Perhaps one of the suppliers decided to save a few pennies, bought bare fans, and printed the mounting frames on a 3D printer from cheap, non-light-stabilized plastic. This goodie sat around for a while, and over time the plastic became brittle. If such a fan fell apart inside a working server in a data center, it’s not even worth imagining.

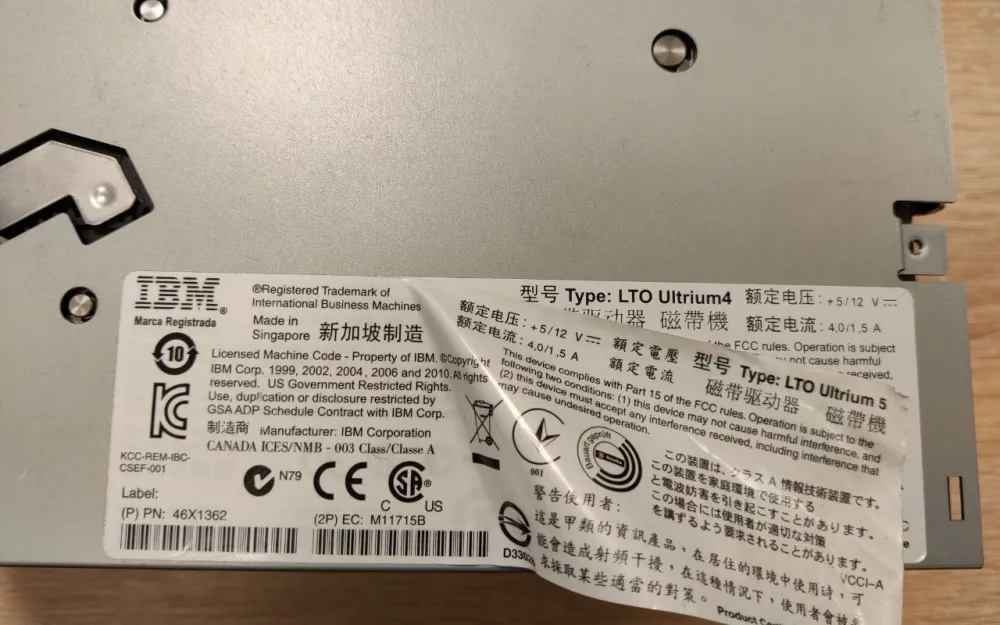

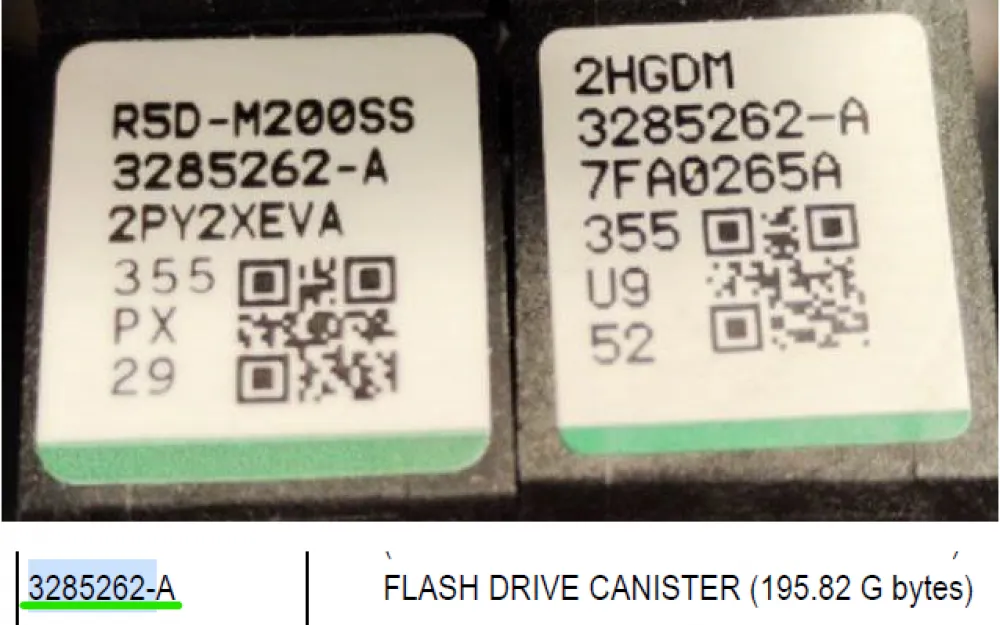

Here’s another example. On the right is the original disk 3285262-A for Hitachi HUS storage systems, and on the left is not. The visual difference is in the model marking R5D-M200SS: this model is for a similar 200Gb SSD, but already from the VSP storage system, the actual article is 5559263-A. And here is a non-original sticker.

The warehouse will verify the article and accept the disk. But further, we need to delve into the documentation and check the model compliance (as well as ensure that the serial number on the disk matches the number on the sled). And even this is not a guarantee that at the next stage we won't reject this disk.

Stage 3. Laboratory Testing

For high-risk categories (DDR4/DDR5 memory, disks), the warehouse automatically generates a request for testing in the system. We maintain a separate incoming control project in Jira. An engineer takes the part, runs it through the stands, and collects logs. We can provide all data to the customer upon request.

Previously, an engineer could launch a board with one processor and a couple of memory sticks, see that the lights turned on, and that was it. Now the regulations have become stricter: the motherboard is only checked with two processors and a full memory setup (for this, we even formed separate sets of processors + coolers + memory for different generations of servers, which are now always at the engineers' disposal).

If the part is original, the system shows a status of "Verified" with logs and screenshots of the diagnostic outputs added by the engineer at the end of the inspection. This is necessary so that a year later, the history can be reviewed to see how exactly that part was tested. If such a status is missing for some reason, and there's a need to fly to a customer in hypothetical Vladivostok, the service engineer can request a special inspection of the spare part before departure.

We try to work with defects based on the principle of "the earlier, the cheaper." If we catch a problem at the entry point or in the first weeks after delivery, we manage to return or exchange the product. But if a problematic component sits on the shelf for a year and only surfaces during a failure, it can only be written off as experience.

By the way, the case with Hitachi added a new point to our regulations. Now, if we need to install disks for upgrading the storage system, in addition to the standard check, we try to put them under load for several days. In the current realities, being cautious is never unnecessary.

Essentially, this verification system for spare parts is no longer just technical control and care for the service's reputation, but insurance for the IT infrastructure and business of our customers.

Conclusion: principles of safe purchasing of spare parts

The main thing I want to say in conclusion: the market is not dead; it has simply started to require a different approach — now any purchase of spare parts begins with a healthy skepticism.

Healthy, because the supplier is not always to blame. We had a case where out of a batch of five new tape drives straight from the factory, two were defective. This was a simple manufacturing defect that can occur in any supply chain. One distributor, for example, ultimately removed tape drives from their assortment altogether, as they couldn't handle the returns.

So it's important not to act impulsively. A problematic supplier is not a reason to immediately write them off. If you abandon partners at the first mistake, you will quickly find yourself in a vacuum. The market situation sometimes forces you to turn to risky sources, and only strict control at the entry point can save you here.

The main recipe for survival today is mandatory checking of any delivery and sharing experiences. It is vital to contact adjacent companies, competitors, and partners. Sharing information about new fraud schemes and sometimes helping each other with spare parts is essential. The more companies start to genuinely check deliveries and return defective items, the faster the market will mature and become orderly again.

What do you think? Share your cases in the comments about how you check spare parts — it would be interesting to discuss pressing issues.

Write comment