- Software

- A

Most people don't care about software quality

On tekkix, there are occasional complaints about the degradation of web design and interfaces for more "primitive" users, the crapification of code hosting, software bloat, and other signs of the world's decline. It seems like every useful website eventually turns into junk with endless scrolling, a dopamine needle, and monetization.

But this degradation has a natural reason, a very simple one. The fact is that most people basically don't care.

Where Have the Small Programs Gone?

Someone might ask, where have the small programs gone? After all, full-featured applications of 100-200 KB used to be the norm, what happened to them? The bloating of software is largely blamed on frameworks: Electron, React Native, and others.

So why did frameworks become popular? The reason lies in the emergence of smartphones. Developers needed to write several native app versions for different OSes, and Electron became the solution to the problem.

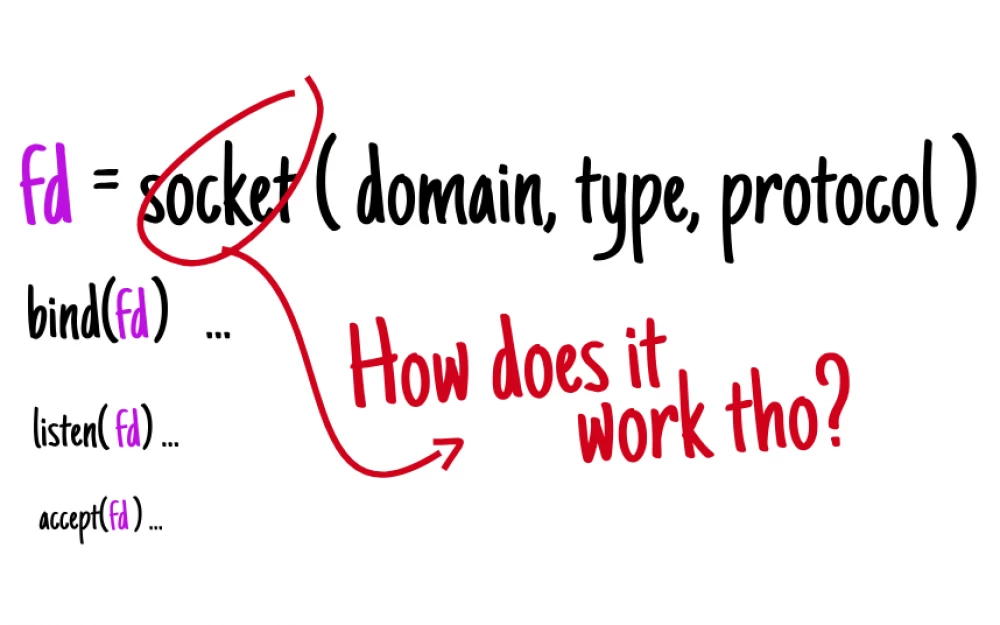

As written in the history of Electron, the real breakthrough for Electron was the combination of Node.js and Chromium: “This solution allowed JavaScript to interact directly with the native capabilities of the OS, while rendering a browser UI, thus providing the highly desirable combination for many web developers.”

This structure simplified the release of a desktop version of a web app, ensuring automatic updates and simplifying the UI development process. But it also brought about well-known problems:

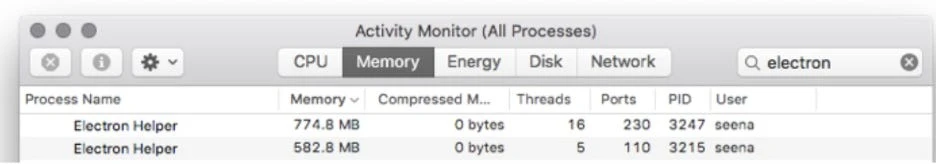

Program bloat, massive memory and CPU consumption. Each Electron app contains its own instance of Chromium:

Decreased performance.

Worsened stability.

So that's how we got to the state we're in now.

Fortunately, for most regular users, none of these problems have become critical. They've gotten used to the unstable performance of apps, and the hardware slowdown has become a given. Most ordinary people simply don't realize that this is an abnormal situation, so they don't complain.

Long-term Software

These days, software is often provided as a service that is “continuously” deployed (CD), wrapped in countless automated tests (CI, continuous integration). This approach makes it possible to hope that the new version will at least work somewhat.

However, there is a vast world where continuous changes are considered evil. On the contrary, people there value reliability and deterministic operation of the program. Software that manages (nuclear) power plants, pacemakers, airplanes, bridges, heavy machinery. In short, where safety is paramount. Such long-term software is developed for decades ahead. All changes are carefully documented and announced in advance.

For long-term software, it is very important to minimize the number of dependencies because each of them can "decay" over time: a new version may be released, the maintainer may change (with the introduction of a paid subscription), or support may stop altogether. At a high level of abstraction, we can talk about four levels of dependencies: from the programming language to working libraries and other easily replaceable tools (helpers):

It is necessary to carefully consider which dependencies will remain relevant in 10-20 years (according to the Lindy effect), and then get rid of unnecessary dependencies and services used by the program. For example, cloud services. All of this can disappear at any moment.

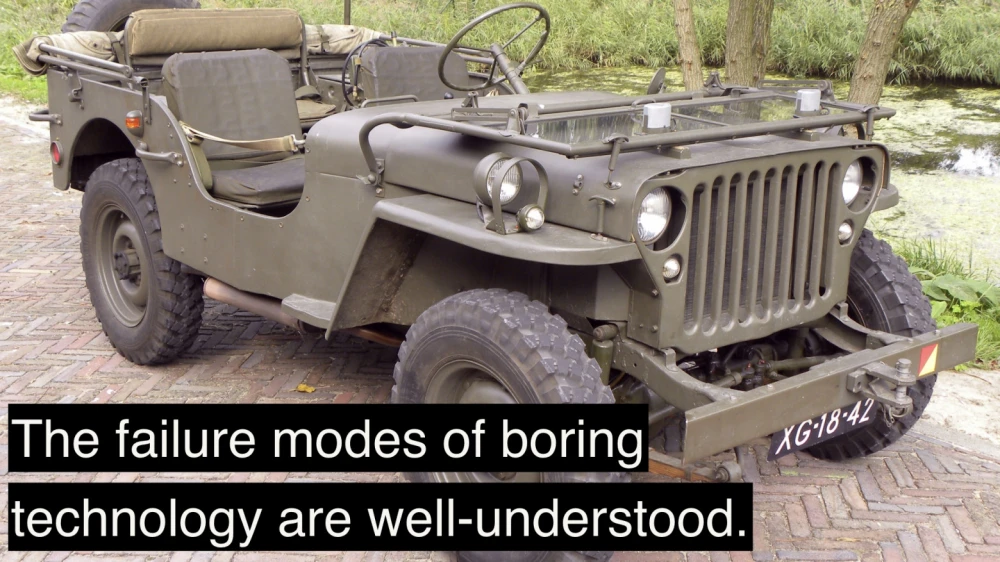

For maximum software longevity, it is recommended to choose the most boring technologies, write the most boring and simple code, like this machine:

To live long, software should also be well-documented, and the source code should be published. This is also a certain guarantee of software quality — many companies require months or years to prepare the code for publication. This means they clean it from unnecessary parts, refactor it, and simplify it to create clean code that they are not ashamed to release. Thus, the very fact of publishing it openly improves the quality of the code.

Long-term software is the opposite of consumer software for the mass market. Some like to create such reliable, predictable, and stable programs. But if we are making consumer software, the rules are different. The mass user is not so concerned with the quality of the software.

Quality — not the main thing?

Sadly, but the mass consumer doesn't care about the quality of programs. This applies not only to software but to other areas of life. For example, take photography. Only a very few users will spend time reading textbooks on photography and composition and then arrange the frames according to all the rules of harmony, with a grid, manually adjusting white balance and exposure to make the perfect, most beautiful shot.

No, most of us just point the camera at the object — and press the button, not particularly worrying about the quality. The shot may be out of focus, with a unbalanced composition, cluttered background, wrong centering, imperfect lighting (lack of light or overexposure with harsh shadows), and other flaws. It doesn't matter. Took the shot, posted it — and moved on.

Ordinary people will not analyze or discuss the flaws in each photo — they won’t even notice them. This is the domain of professional photographers. Similarly, a professional designer will immediately spot flaws on other people’s websites: lack of keyboard navigation, poor kerning, no breathing space around illustrations, and dozens of other issues. But 99% of users simply don’t care because it doesn’t affect them.

Some designers chase perfection that will never be noticed by non-professionals. They may take pride in their craft, but most people physically cannot tell the difference between good and bad design.

There is an excellent essay by Will Tavlin titled “Casual Viewing. Why Netflix looks like that”. In it, the author rightly criticizes Netflix’s model of producing large amounts of low-quality content for an undemanding audience that watches films in the background. For example, one of Netflix's requirements is that the main character must always verbally state what they are about to do on screen.

Creative people are horrified by the aesthetics, poor scripts, and complete lack of creative talent. All the movies and shows seem mediocre, and Netflix's principles clash with traditional techniques of theater and filmmaking (“Show, don’t tell”). But ordinary people just don’t care. They consume content as if nothing’s wrong.

Interface, design, and ergonomics specialists see flaws everywhere — even in the interface of an ordinary coffee machine. Different models have completely different control logics. Buttons, sensors, displays — everything is arranged differently, without any standard.

The same goes everywhere. Professionals see flaws, but ordinary people don’t. They don’t understand the subject, don’t know the context, and don’t dive into the professional field of creating these objects. That’s why they are quite relaxed about the low quality of everything around them: from food to household appliances design.

This also applies to software. Professional developers immediately see the flaws: bloated software, inflated mobile apps, sluggish 2D graphics on the powerful CPUs of modern smartphones, which in terms of performance can rival the supercomputers of the past. But ordinary people don’t see any of that.

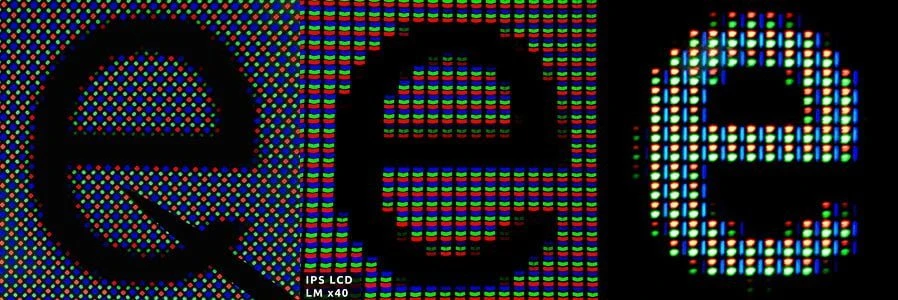

In principle, the professional expertise of developers or designers reflects in perfectionism, extreme attention to detail. For example, designers study the pixel grid on displays of different mobile devices to calculate the optimal subpixel rendering:

Audio enthusiasts discuss the insane sound compression in modern music, leading to "loudness wars" and compression of dynamic range. They complain about the quality of MP3 compression and cannot listen to music in mediocre headphones or in rooms without sound-absorbing walls. But for ordinary people, it doesn't matter. We just listen.

Similarly, ordinary people just launch programs — to simply do what they need, they press the buttons of applications without thinking about the fact that these buttons are not optimally placed.

Perhaps professionals should not take the enshittification of everything around them personally? Maybe it is a normal trend for the modern world, where the majority reigns?

Most people really don't want to spend cognitive energy understanding subtext. For example, the political subtext in superhero movies. People often watch movies "in the background," just for the pleasure of shots and so on.

If the public accepts a mediocre mass product, why bother? From a business perspective, it is unprofitable to spend extra resources to perfect it. It is enough to release a "minimum viable product" that satisfies 99% of consumers.

It is not that most people are undemanding or poorly educated. No, it’s just that all of us are amateurs in the vast majority of fields. In everything where we are not specialists.

That's why most people don't care about the quality of software.

To be more precise, people actually don’t not care, but they usually lack the competence, attention, and time to distinguish a quality product from a poor one. So the result is inevitable. Most people eat tasteless vegetables and fruits from supermarkets, watch silly movies, run apps that are gigabytes in size — and live their happy lives, not worrying about anything. And this is an endless process. People get used to everything, so the quality of goods/software/mass culture gradually degrades naturally. Movies get worse, food becomes lower quality, and software gets buggier — perhaps all this happens for natural reasons.

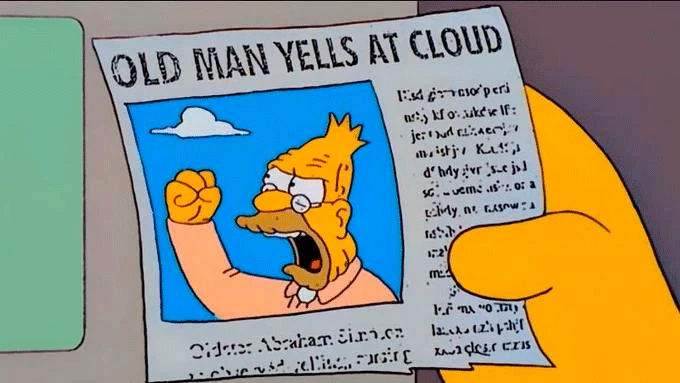

Periodic complaints from professionals about this remind me of old man Abe Simpson:

Write comment