- AI

- A

The War for Talent in AI

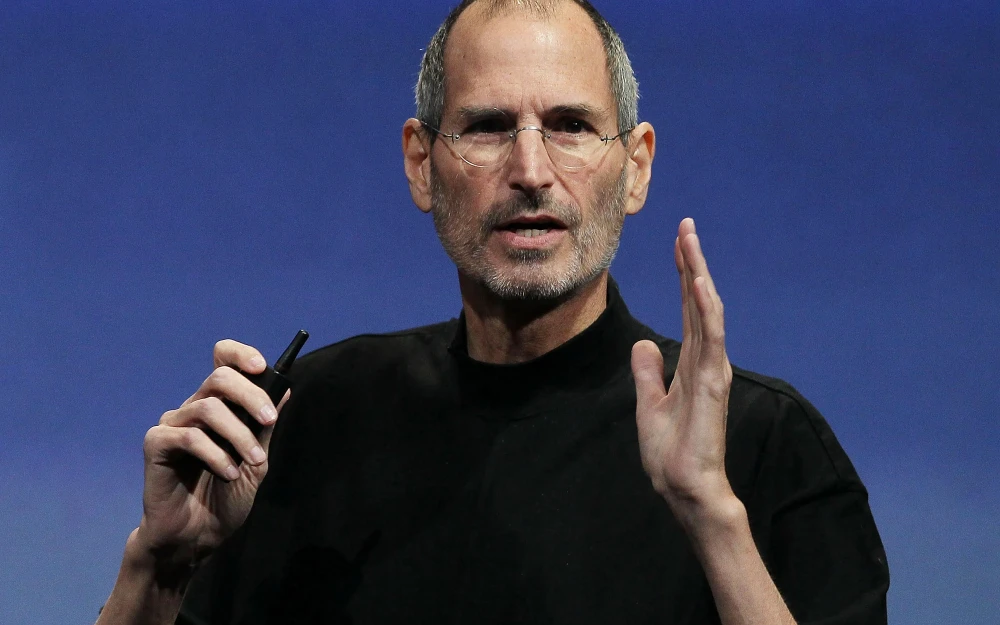

The late Steve Jobs cannot be called a "man of letters," but he certainly enjoyed writing sharp emails.

The late Steve Jobs cannot be called a “man of letters,” but he certainly loved to write sharp emails. One of the most famous works of the Apple Inc. co-founder is a 2005 memo to Bruce Chizen, who was the CEO of Adobe Inc. at the time:

Bruce,

Adobe is hiring employees away from Apple. They’ve already hired one person and are calling many others. We have an unwritten rule with recruiters: we don’t hire people from Adobe. Looks like you have a different rule. One of us has to change this rule. Please let me know who exactly.

Steve

This email, like many others, was presented as evidence in the dramatic legal battle between the Justice Department’s antitrust division, eight Silicon Valley companies, and tens of thousands of tech professionals who claimed their earnings were cut due to a conspiracy between company executives. The companies—Apple, Adobe, Google, Intel, Intuit, eBay, Pixar, and Lucasfilm—were eventually forced to pay nearly $500 million in compensation.

Thanks to his knack for choosing words, Jobs found himself at the center of one of the most high-profile cases in the history of the American tech industry. “I would be very happy if your HR department stopped this,” he wrote to Google President Eric Schmidt in 2007, forwarding a cold email from Google’s HR department. The recruiter was immediately fired.

In a separate incident, Google co-founder Sergey Brin told colleagues that Jobs had “angrily” called him and threatened “war” if Google continued its attempts to poach engineers from Apple’s web browser team. Brin ordered that no further offers be made until they “got permission from Apple.”

“There was no doubt that they were colluding,” recalls economist Orly Ashenfelter, who testified in one of the civil cases. The legal consequences “became a lesson for HR professionals at various companies and showed what is actually permissible and what is not. The question is, how long will this lesson last?”

Today, as some of the same players engage in talent wars in the AI field, we are beginning to understand what Jobs feared: the ruthless battle for the best professionals, where the employees hold all the cards. The best engineers are hunted like senior pitchers and star quarterbacks. For example, Meta Platforms Inc. offers “salary packages of up to $300 million over four years,” according to Wired’s sources. (Meta disputes the wording.)

Regardless of the size of the packages, the aggression raises serious concerns among company executives. “Right now, I feel an internal sense like someone broke into our house and stole something,” wrote OpenAI Chief Scientist Mark Chen in an internal memo obtained by Wired.

I suppose few people feel sympathy for those at the top, but ordinary employees face other risks. According to Ashenfelter, such extravagant packages change the compensation system that provides a semblance of fairness within a company. Didi Das, an AI investor at Menlo Ventures, told Business Insider that this leads to “feelings of jealousy, envy, and helplessness.”

But OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, despite intense competition, understands there's no point trying to repeat Jobs’s approach and interfering with companies poaching his talent through backroom deals.

However, the major players seem to increasingly despise each other.

More importantly, talented AI engineers can work not only at the biggest companies.

“Compared to the past,” notes Firas Saouzan, CEO of the technical recruiting firm Harrison Clarke, “you don’t need many engineers to create a product. I think part of why Mark Zuckerberg is doing this is that a talented engineer is ultimately going to go to Intel Capital or Andreessen Horowitz and get an offer to start their own company.”

As a result of all this, we might see tech companies once again trying to convince employees their role is not just a job, but a calling that matters more than the number of commas in their paychecks. “Are the reasons people take jobs becoming less about compensation and more about what’s actually being built? 100%,” Saouzan says.

To keep employees from leaving, OpenAI claims that artificial general intelligence is the company’s only true goal and that all of its work is focused on achieving it, while those working on AI at Meta will, at least some of the time, be thinking about how it can be used to show your grandmother bad viral videos more efficiently. “Missionaries will beat mercenaries,” Altman told staff in a memo.

Ilya Sutskever, co-founder of OpenAI who left to launch his own startup Safe Superintelligence, assured employees he wouldn’t consider offers to sell the company amidst rumors Meta tried to buy the entire team. “We have the compute, we have the team, and we know what to do,” he wrote. “Together, we will continue to build safe superintelligence.” Nevertheless, it seems he lost his CEO Daniel Gross to Meta.

In the era of post-pandemic layoffs—which, for those not working in AI, is still ongoing—talk of going above and beyond has gone a bit out of fashion, but I wouldn’t be surprised if a new version of this trend emerges.

AI companies can’t rely on the intimidation tactics that Jobs used to keep employees from seeking better, more lucrative opportunities.

Instead, leaders have to convince employees that their work in AI will matter more than anything in history.

Whether employees will believe them is another question.

Write comment