- AI

- A

AI Will Replace Programmers in a Year, but Can't Find Bugs in NGINX Config

The head of Anthropic stated that AI will replace engineers within 6–12 months. It sounds scary until you ask the neural network to fix the NGINX config in a real project. This article is my "diary of AI mistakes," analyzing the differences between benchmarks and production, and thoughts on why vibe coding won't save you from responsibility.

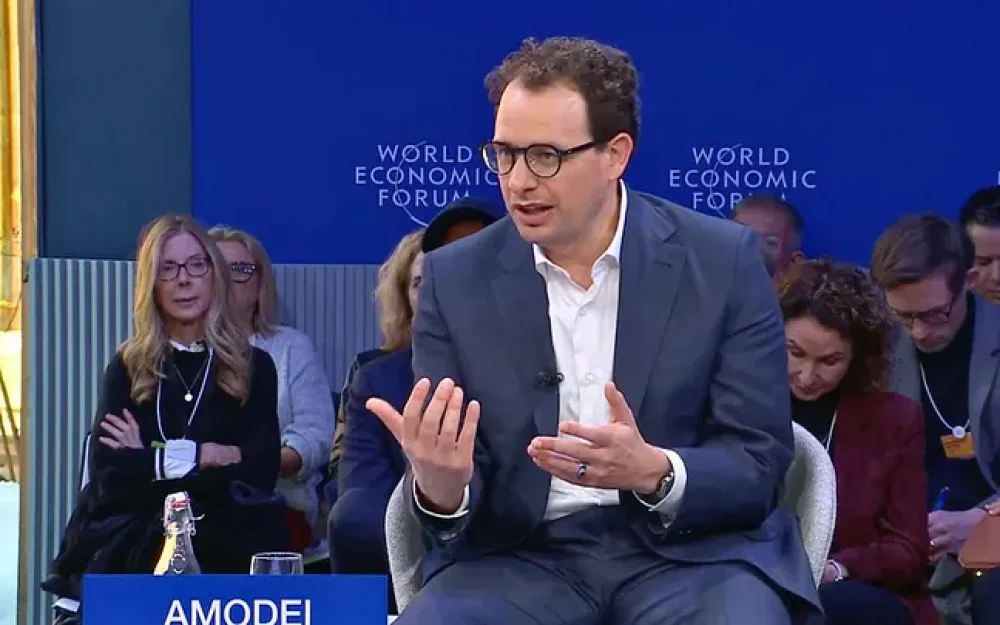

Two weeks ago, Dario Amodei spoke at the World Economic Forum and made a statement that caused many to raise their eyebrows: in 6-12 months, AI will be able to do everything that a software engineer does. Not "help." Not "accelerate." Exactly — everything.

I've been in backend development since 2016. I started with PHP, then Python, and now mainly work on backend across various stacks. During this time, our profession has been declared dead about fifteen times: low-code will kill it, no-code will finish it off, outsourcing to India will consume everyone. We are like that guy from the joke about the mother-in-law and two broken accordions.

But this time, the source deserves attention. Amodei is not an info-gypsy with courses on "entering IT in three days." He is a person who is building one of the most advanced AI companies on the planet. When such people make predictions, it's worth at least investigating what lies behind them.

Let's figure it out.

What exactly was said and why everyone rushed to write articles

Amodei stated at the WEF that we are 6-12 months away from AI systems that will be able to perform everything that a software engineer does.

At the same time, Anthropic released updated benchmarks for Claude Opus 4.5. The numbers are indeed impressive: growth in SWE-bench, improved performance with long context, and the ability to keep track of the architecture of large projects. What used to be a clear weakness — working with a codebase of 50+ files — seems to have improved.

For context: SWE-bench is a benchmark where models are given real bug reports from open projects and asked to write a patch. The task is clearly defined, there are input data, and there is an expected result. Claude Opus 4.5 shows results at the level of 50%+, which just a year ago seemed fantastic.

And this is where it gets interesting.

About benchmarks and reality: why these are two very different things

I have a friend named Sasha. A year ago, he got a job at a large company after acing all the algorithmic interviews. He solved LeetCode hard problems at speed. And then he couldn't close a single ticket on a real project for three months.

Why? Because real work is not about algorithms.

SWE-bench tests a model's ability to solve isolated, clearly formulated problems. You are given a repository, a bug report, and you need to write a patch. Great. A controlled environment, clear boundaries.

And now, my last working week.

Monday: call with the product manager who wants "something like Notion, but not quite." I spend forty minutes figuring out what exactly he means. It turns out — he doesn't know himself. I sketch three options. He chooses a fourth one that doesn't exist.

Tuesday: found a bug that occurs only with one client out of a thousand. After two hours of debugging, I realized that their database has data leftover from the 2019 migration. The person who did the migration has left. Documentation? Ha-ha.

Wednesday: code review. A junior wrote working code, but architecturally it's a ticking time bomb. I explain why. He doesn't understand. I draw diagrams. We argue for an hour. In the end, we find a compromise that satisfies both.

Thursday: the product manager changed his mind. Now he wants it differently. I redo half of what I did on Tuesday.

Friday: deployment. Something crashes. We roll back. It turns out the API of the third-party service we are using changed. Without warning, of course. A hotfix on the fly in two hours.

Where is the place for AI that "does everything" in all of this?

What AI can really do — and that's already a lot

I don't want to be that bore who denies the obvious. AI tools have really changed my work over the past year and a half.

Copilot and Claude for code. Saves a ton of time on boilerplate. Need to write 15 similar tests with different parameters? It can handle that. CRUD endpoint by template? Easy. Data conversion from one format to another? Almost no editing required.

I actively use Claude Code — I even recently gifted myself an Anthropic Max subscription. Building a website prototype in an evening, writing a CLI utility, automating routine tasks — all of this really works. I'm thrilled with the possibilities it opens up.

A rubber duck with an IQ of 150. Sometimes it's easier to explain a problem to Claude than to a colleague. It doesn't interrupt, doesn't go off on a call, doesn't say "well, in our last project...". And often suggests directions I hadn't thought of.

Refactoring by template. "Replace all singletons with DI" — you get a working draft. Not perfect, but 80% of the work is done.

Documentation. Previously, this was the most hated part of the job. Now it's just hated. Progress!

So yes, there is a benefit. And it's noticeable. But.

My diary of AI mistakes: where it breaks

I have been leading for half a year. Not to hate — I'm trying to understand where the boundary is.

January 12. I asked Claude to help optimize a query to PostgreSQL. He suggested adding an index. A reasonable piece of advice. Except the table has 800 million records. Adding an online index in our version of PG would lock the database for about three hours. How would he know that? Nowhere. But I know because we got caught like that a year ago.

January 19. I was debugging an authorization issue. The AI confidently pointed to a specific section of code. I checked — everything was clean there. I spent two hours verifying its hypotheses. Then I gave up and went to read the logs myself. It turned out the problem was in the nginx config on another server. The AI only saw the code I showed it. And the bug was outside.

January 25. A classic case. I asked to fix bug A. It fixed it, but broke feature B. I asked to fix B — it broke A back. And so on three times until I realized that the model did not see the connection between these parts of the system, even though I explained it to her. I had to figure it out myself and provide specific instructions.

January 29. I asked to write an integration with an external API. I got beautiful code that didn't work. Why? The API documentation was flawed (there was an error in the example), and the AI honestly copied it. I know that this API is glitchy because I worked with it before. The AI does not.

February 1. I asked for help with migrating the database. The model proposed a plan that looked logical. Only it didn't know that we have triggers historically tied to specific column names, and renaming them would break half of the reporting. This information was in a comment to the three-year-old code that no one reads.

Do you see the pattern?

Everything that requires context beyond the visible code is a failure. Everything that requires history is a failure. Everything that requires knowledge like "this service always lies in the logs" or "this client never updates the browser" is a failure.

The problem of context: the main one, in my opinion

Software is not just code. Software is a history of decisions.

Why is this service in Python, even though it should be in Go for the load? Because three years ago, the only Go developer quit a month after the project started.

Why is there a strange workaround with a timeout of 47 seconds? Because a key client’s proxy cuts connections exactly at 50, and we figured this out at 3 AM after an incident.

Why is this microservice called legacy-bridge-temp-v2-final? Better not to ask.

Where is this written? Nowhere. It's in people's heads. In Slack conversations from 2021. In Jira comments that no one reads. In the memory of those who were there.

AI does not know this. And it won't know until you feed it the entire history of the company, including informal kitchen conversations.

I have thought a lot and written a little on Habr about memory in modern AIs — ChatGPT and Claude maintain lists of facts about the user and search through chat history. This is useful, but complete adaptation is still far away. Models often get stuck on one or two facts and poorly understand the context. Sam Altman has said that the current memory is just a prototype, and in GPT-6 they will try to implement full user customization. We'll see.

Business motivation behind loud statements

I am not a cynic. But I have worked long enough to understand how corporate communications work.

Anthropic is a company that raises billions of dollars in investments. They compete with OpenAI and Google. Every public statement by the CEO at the World Economic Forum is also marketing.

When Amodei says, "In a year we will replace programmers," what does the CTO of a large company hear? "We need to urgently implement AI before competitors get ahead." What does the investor hear? "The market is huge, we need to invest."

This does not mean that Amodei is lying. Perhaps he genuinely believes what he says. But he has structural reasons to be optimistic. I do not have such reasons.

For context: OpenAI is expected to incur cumulative operating losses of $115-143 billion by 2028 inclusive. Profitability is planned for 2029, for which the company needs to reach revenue of $125-200 billion. Currently, revenue is about $13 billion. AI companies desperately need the market to believe in their future.

Remember the forecasts from 2015 about driverless cars. "In five years, everyone will be driving robot cars!" Ten years have passed. Waymo operates in several cities. Tesla still requires keeping hands on the wheel. Mass adoption is as far away as the Moon.

There is a chasm between "technically possible in laboratory conditions" and "works at scale."

A question no one wants to ask

Okay, let's say AI starts doing all the "dirty work." Junior positions will disappear. Internships will become a thing of the past. Companies will stop hiring newcomers because it's cheaper and faster to use AI.

And who will be seniors in ten years?

I became who I am because I wrote a ton of bad code. My solutions broke production. I stayed up until three in the morning figuring out why what was supposed to work didn't. I received comments on code reviews like "this is absolutely unacceptable" — and I learned.

Without that experience, I wouldn't understand why certain architectures are ticking time bombs. I wouldn't feel where the system might break. I wouldn't know what questions to ask.

If juniors don't write code — they won't become middles. If middles don't architect — they won't become seniors. We will remain — a generation that learned "the old way."

And then we will retire.

Maybe by then AI will be smart enough. Or maybe it will turn out that we've raised a generation of people who can prompt but don't understand how systems work.

On the other hand, I often read that AI-first companies, on the contrary, love to hire juniors — they adapt to AI tools faster and better. It's possible this is the solution. Or the market will develop in a completely different way.

The Jevons Paradox: what if everything is the opposite?

There's an interesting theory that I recently discussed with Django co-founder Simon Wilson. The Jevons Paradox — when a resource becomes more efficient due to technology, the demand for it doesn't decrease, but rather increases. When steam engines became more efficient in the 19th century, coal consumption didn't fall, it soared.

Could this work for programming?

Look, there are two possible scenarios:

— AI makes code ten times cheaper → demand for programmers drops by ten times.

— AI makes code ten times cheaper → small companies and even individuals start ordering custom software for their tasks → demand for programmers skyrockets.

Programming has historically gone down the path of simplification. When Grace Hopper promoted compilers in the 1950s, it faced huge resistance. "Code will be slow and unstable!" By the end of the 1950s, more than half of the code at IBM was written in Fortran. Entry into the profession became easier, development became more accessible.

At the same time, assemblers have not suffered. Today, there are probably even more of them than in the early 50s — low-level programming is critical for operating system kernels, drivers, and embedded systems.

Previously, a huge number of medium and small businesses could not afford software for their own requests. Now, something decent can be done even by oneself by paying for a subscription to AI. Some will do it themselves, while others will pay a professional — who will collect it even faster and better with the help of the same neural network.

A specific example: why this cannot be automated

The last major project. Without NDA details.

Task: break the monolith into microservices.

First month: understand where to draw the boundaries. This is not a technical solution — it's a business one. Which parts of the system evolve independently? Which teams are responsible for what? Where are the bottlenecks? Which clients use what?

Second month: politics. Two departments that historically do not get along must agree on the API. An hour of negotiations. Compromises. "Vasya, we are working together, why are you again..."

Third month: legacy. A component from 2014. The author has left. No one knows how it works. But a critical business process depends on it. Rewrite? Wrap it? Partial refactoring? Trade-offs everywhere.

Fourth month: smooth migration. Canary releases. Monitoring. Feature flags. Rollbacks.

Fifth month: the first major incident on the new architecture. Three hours of investigation at night. It turns out that one of the microservices behaves differently under load than in tests. Because in tests we did not account for the pattern of requests from real users.

Where is the "AI does everything" here?

My theory for the coming years

AI will take over routine tasks. It is already doing so. And that’s good.

The boundary between "code" and "specification" will blur. Instead of "write a function" — "make it so that the user can X."

The value of a programmer will shift from "can write code" to "understands systems" and "can formulate tasks."

Some people will lose their jobs. Especially those who engage in pure implementation without understanding the context.

The need for people who make decisions, take responsibility, and sort out the mess of real systems will not disappear.

At least, not within a year.

What to do specifically

Master AI tools. Those who master them earlier will gain an advantage. I have already written: to become more effective with AI, you need to understand how it works. Know about knowledge cutoff, be able to prompt, and validate results.

Andrei Karpathy recently wrote that for the first time in his career, he feels "behind" — the profession is changing rapidly, and one must master a new layer on top of regular development: agents, prompts, context, integrations.

Develop what AI cannot do. Understanding systems. Communication. Decision-making under uncertainty. Explaining complex things in simple language. Negotiating with people.

Document. If you understand how the system works — that’s valuable. As long as it’s in your head — you are irreplaceable. Once it’s written down — AI can use it. But you still need to document everything.

Observe without panic. Read not just headlines, but technical details. Understand what really works and what is just marketing.

Experiment. Try using Claude Code on a real project. Try to vibe code something of your own. Understand in practice where AI succeeds and where it does not.

About vibe coding and responsibility

I want to specifically mention a trend that I see more frequently. People are using Claude Code and similar tools to build applications for themselves — from managing smart homes to clever add-ons over banking software.

This is cool. But there’s a downside.

No matter how flawed the official application may be, the company is responsible for its operation. If something goes wrong — we contact support or go to court. When you’ve vibe coded the application yourself — you are responsible.

And it’s fine if it just flashes lights. What if it locks the front door? Or sets the heating to maximum at night? Don’t even get me started on security holes.

There are two solutions. First, don’t forget to use AI for testing — at least ask the same neural network to run basic tests. Second, I’m sure applications with an "AI layer" will emerge — a professional is responsible for the engine, while the user creates the interface for their tasks with the help of the neural network.

In summary

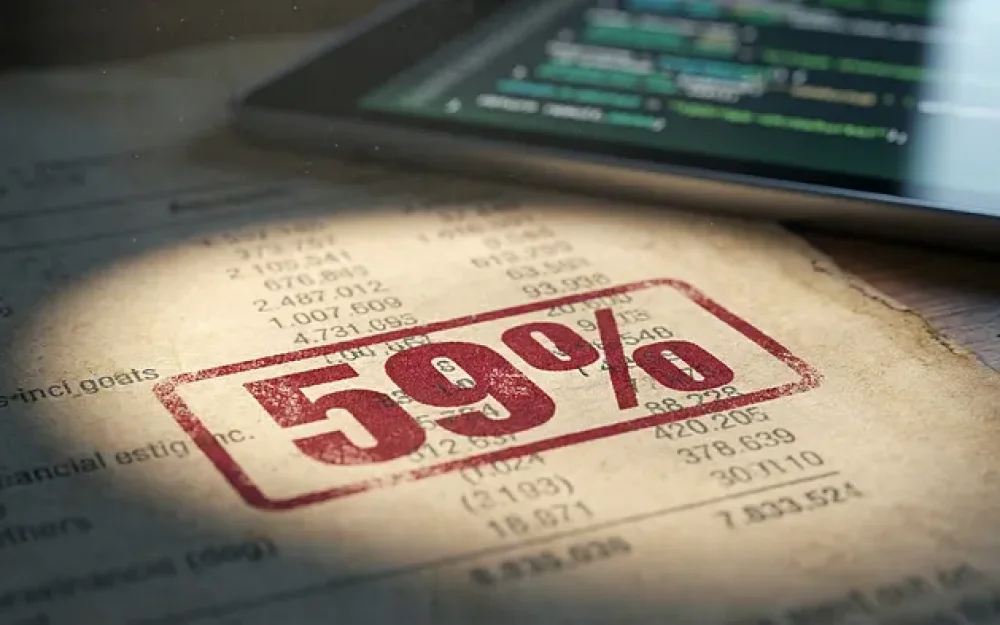

In a year, we will NOT be out of work. IMHO, I am 85% confident about this.

In five years, work will look different. In ten — completely different.

It has always been this way. The speed of change is simply higher now.

Amodéi may be right about the technical capabilities. In a year, AI may well generate code at the level of an average engineer.

But generating code ≠ being an engineer.

An engineer understands the mess. Makes decisions when there’s no clear answer. Explains to the business why it will take three months instead of a week. Takes responsibility for the consequences. Negotiates with people. Remembers why they decided to do it this way three years ago.

AI does not yet take responsibility for the consequences. AI does not yet remember the context. AI does not yet know how to negotiate with Vasya from the neighboring department.

When it learns — then we can talk.

P.S. If you think I’m missing something — write in the comments. I'm seriously interested. I could be wrong, and it would be helpful to hear other perspectives.

Sometimes I write about such things in tokens to the wind — sometimes about how LLMs think, or just pretend.

Write comment