- Network

- A

How and why Blue Origin is creating another satellite network

For many years, satellite communication was seen solely as a backup option for places without cable, mobile networks, or any signal at all. In fact, not much has changed in this regard today: it is still commonly believed that satellites are complicated and expensive. Perhaps for personal access to the network, it is still an acceptable option, but it is definitely not suitable for serious data volumes. For this reason, until recently, no one considered them a full-fledged part of internet infrastructure, especially backbone.

Starlink has certainly changed the situation for some regular users. However, for transmitting huge flows of data, say, between data centers and cloud platforms, these networks are still unsuitable due to architectural limitations. And now Jeff Bezos is presenting the TeraWave project, which proposes using satellites as a high-speed transport channel. Let's try to understand what this is and why it's needed.

Not "another internet from space"

TeraWave is positioned as a specialized backbone, originally designed to handle vast amounts of traffic. That is, the project is intended for corporations, not for servicing regular users.

The claimed 6 terabits per second is the total bandwidth of the entire system, which is designed for data transmission between data centers, cloud regions, and computing clusters. Essentially, TeraWave is closer to classic internet backbones: it acts as a transport layer for large and stable traffic flows, rather than for millions of individual connections.

Instead of fiber optics, this system uses satellites with inter-satellite laser channels (more on this below) and a small number of ground stations. This should simplify routing and allow operators to direct some traffic through orbit when terrestrial lines are overloaded or unstable.

At the same time, TeraWave does not intend to replace cable infrastructure and does not compete with it directly. The project is designed to take on part of the interregional and intercontinental traffic. Another caveat is that there is no duplication of Project Kuiper in this project. The latter addresses access for end users, while TeraWave is meant to serve as a backbone for corporate clients.

Two levels of orbit instead of one and lasers

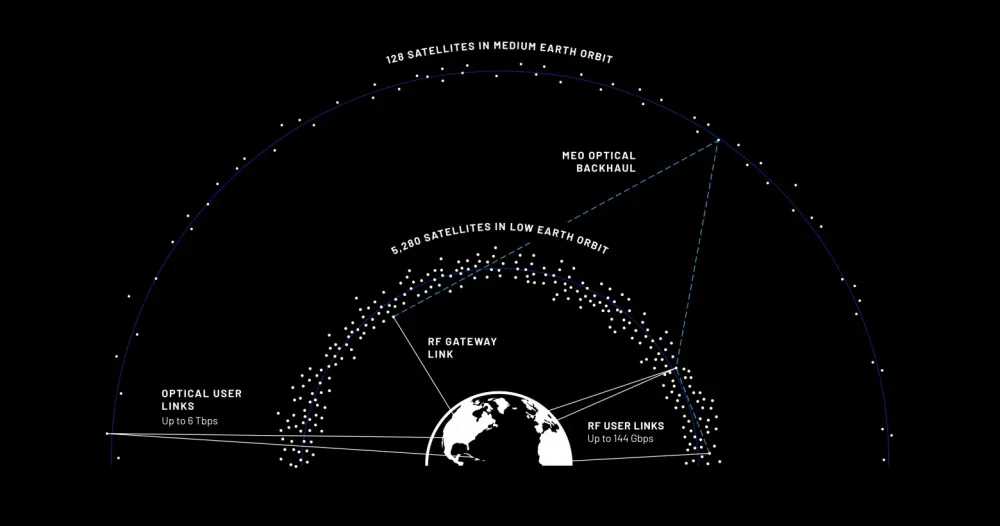

The architecture of TeraWave looks unusual compared to the familiar Starlink. The latter uses thousands of identical devices, connected in a network, while TeraWave is divided into two levels.

The lower level consists of 5,280 satellites at altitudes from 520 to 540 km. They are expected to provide channels up to 144 Gbps and distribute traffic between ground objects and the network as a whole.

The upper level consists of 128 heavy satellites in medium Earth orbit, at altitudes from 8,000 to 24,200 km. These devices will act as backbone nodes, maintaining communication with each other and with Earth using lasers. Due to their high orbit, they will be able to cover a larger area.

By the way, about lasers. This is actually the key technology of TeraWave and at the same time its main limitation. Such channels allow data to be transmitted with very high density and minimal latency. In the relative vacuum of space near Earth, these lines should operate almost perfectly and exceed the speed of signal propagation of traditional fiber optics.

However, as soon as it comes to interacting with ground infrastructure, nuances arise. The atmosphere is not very friendly to lasers: fog, rain, dust, and all that can significantly degrade the quality of the channel. For this reason, TeraWave does not abandon the radio frequency segment but uses it as a backup and complement.

As a result, a hybrid system is created. The idea is that under normal conditions, the main load will be on lasers, and in the event of worsening weather, traffic can be partially or completely switched to radio communication. The speed will decrease, of course, but the channel won't go down. For corporate and government clients, such predictability is often more important than record numbers in specifications.

Why there are only 100,000 clients

One of the most unusual statements regarding TeraWave is the limit of about 100,000 connections. For the consumer market, this would seem strange, if not disastrous, as companies usually operate on the principle of "the more, the better." But in this case, the number simply reflects the project's specialization in a narrow segment of users.

TeraWave is designed for clients who need symmetrical channels with guaranteed bandwidth. Data center operators, financial institutions, government agencies, large scientific organizations—all of them work with data volumes that cannot be serviced within the framework of ordinary satellite networks, or it is extremely difficult. They require stability, low latency, and independence from terrestrial infrastructure. One such client can generate revenue comparable to thousands of household connections. In this sense, the limited number of subscribers no longer seems to be a problem.

Considering TeraWave as a standalone business project would not be entirely accurate. It logically fits into a broader strategy of Blue Origin, focused on developing orbital infrastructure. While this may seem like science fiction for now, it appears that Bezos's company is seriously aiming to find itself in the future with space stations, orbital research complexes, and lunar manufacturing modules that will generate huge volumes of data.

Write comment