- AI

- A

Underwater Rocks of Vector Search in the Knowledge Base

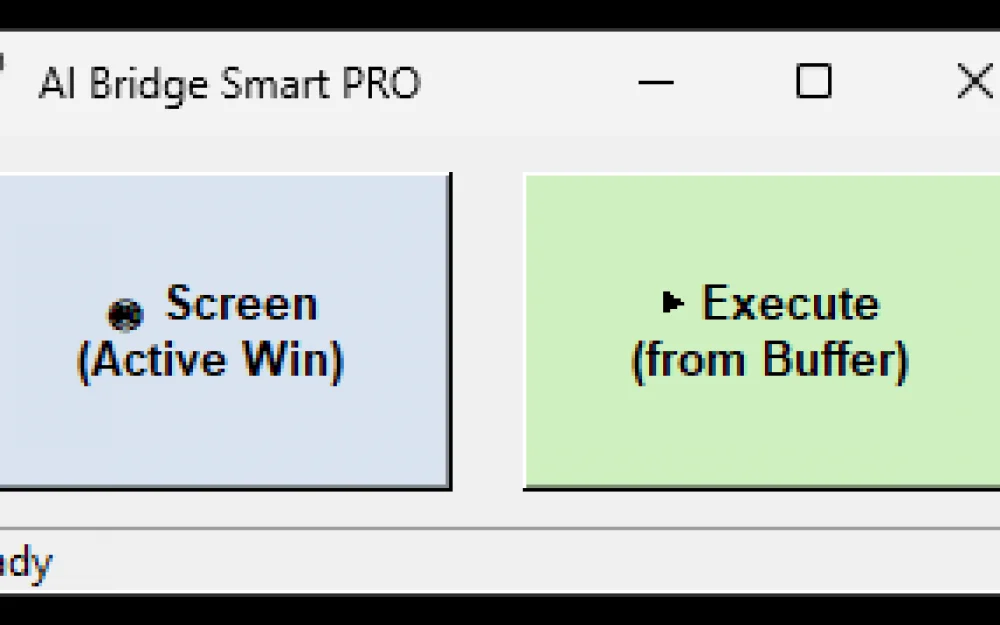

Today I want to share my experience implementing vector search functionality for articles in the knowledge base. The results of vector search for articles from the KB are displayed in the chatbot as instructional articles that the user reads and executes. The functionality seems simple, however...

A person asks a question in the chatbot

The vector search looks for a suitable article in the knowledge base and the article is shown to the user

If no suitable article is found, it switches to an operator

Simple? That's what I thought too. After promising the functional customer to deliver a ready-to-use search solution (for about 10,000 articles in the KB) in two days, I sat down and indeed wrote a basic vector search in a couple of days:

All articles (which are also responses to the user) from the KB are "digitized" into embeddings and stored in a vector index (FAISS)

The text coming from the user is converted into an embedding vector in the same way

Then we search using the cosine similarity algorithm for the N nearest articles in the database and return them as a response

If the cosine similarity value is less than 0.5 (I intuitively considered this threshold reasonable), we switch to an operator

After testing that everything works "as it should" (from my amateur perspective at that time), on the evening of the second day The cadaver fully satisfied I went to sleep, not even suspecting that I had done less than 1% of what actually needed to be implemented. As a result, the task reached production only after six months of long and hard development by a team of several people.

Below are the most labor-intensive problems we encountered when trying to implement the functionality described above in production. After a brief listing of these "pitfalls," I will explain how each of these problems was solved.

Quality of search evaluation. How to understand that the model is searching well? And how to know if the search has improved after the “upgrade”? Which embedding model to use for search that will yield more accurate results? It is clear that the model should be BERT, but there are countless variations; one can either randomly pick one or conduct some tests to compare them with each other. Immediately, the task of quickly (automatically, of course) testing the quality of the vector search results arises.

Different size of articles and user queries. The article in the knowledge base is large (compared to the user’s query), and the embedding vector derived from it is skewed by a whole bunch of words contained in this article. However, the user usually writes a much shorter version of what they need in their question. As a result, even if the article contains the user's query almost 1:1, the other words in this article shift the embedding vector in such a way that it leaves the model little chance of finding a match between the user’s query and the article in the knowledge base.

Different language/style of articles in the knowledge base and user queries. Articles in the knowledge base are typically written in a language that is quite different from that spoken by users. For example, take any major company’s website and see how a service they sell is described – it’s high-quality, beautifully written with gerunds and adjectives that are not easily understood by the average person. On the other hand, the user is an average individual who doesn’t speak in “high style” and writes in plain conversational Russian, sometimes even using profanity.

No suitable article. How to determine that there is no “suitable” article in the knowledge base? A soulless model ALWAYS finds “suitable” articles, and the absolute value of cosine similarity won’t help here at all. One cannot say that if the value is less than 0.5, then the article is unsuitable, while if it's more than 0.5, it is suitable. Testing has shown that articles with a similarity of 0.7 can be completely unsuitable from the perspective of an ordinary person, while those with 0.3 can adequately respond to the user’s question. How can we tell whether we misunderstood the user’s question, or if the article is genuinely absent in the knowledge base?

Switching to an operator. The client wanted to summon an operator not only when a suitable article is absent in the knowledge base, but also when the user is furious, starts writing “negativity,” or clearly calls for an operator. How to understand that a person is writing negatively and calling for an operator? “Profanity” - okay, that can be tracked somewhat through a dictionary, but how to track phrases like “call the leather bag, soulless piece of metal”? And how, for example, can we understand that the phrase from the user “have you all gone completely crazy” is negative, and not a question about lanterns?

Feedback. How to get feedback from a person about the performance of the search system? Simply asking a person to rate it (for example, thumbs up/down) isn’t entirely relevant; a person might just dislike the content of the article and “downvote” it because their problem isn’t solved, even though we found the most suitable article in the knowledge base.

Duplicate articles. How to deal with duplicate articles in the knowledge base. Knowledge bases are maintained by people, and they very often make mistakes and create duplicate articles. Especially in our case, where there are about 10,000 articles in the knowledge base, and dozens, if not hundreds, of administrators adding articles. The end user typically becomes confused if the chatbot shows them two practically identical articles/responses. The user will be looking for the catch, unaware that it’s simply the editors’ clumsy hands that added two nearly identical articles.

Further in the article, there will be an analysis of each problem and the way we have currently solved this problem. I must say right away that these are far from all the issues we encountered during the development and implementation of the solution, but in my opinion, they are the most important and typical, and I hope they will help readers to be proactive in addressing their resolution. I would be glad if you share your experiences in the comments and tell what problems you faced when solving a similar task.

1. The problem of evaluating search quality.

So, on the morning of the third day, after the "successful completion" of the task, I was very surprised to find that the functional client was completely dissatisfied with the resulting solution. His feedback on my solution was as follows: “What kind of junk did you make, it doesn't search for what is needed at all.”

The first thing that came to my mind to check my solution (“what if there really is a bug somewhere” - I thought) was to take some standard metric and see how good the search is. I decided to try the rouge metric - such a naive attempt to algorithmically (i.e., without spending much effort) understand how good my search is. And it became clear almost immediately that any algorithmic check of the result is impossible because if one algorithm searches better than another algorithm, one can simply replace one with another :). It is necessary to annotate the data (i.e., prepare a test dataset) manually. That is, we take a real user query, manually find an article with a knowledge base for it, and create a verification dataset from such “manual” examples.

I asked the client to send me specific examples where, in his opinion, my search makes mistakes and produces incorrect results. After receiving three random examples, I realized that I had no idea how these three unfortunate examples would help me improve the search. It became clear that I needed to "shake" the client for many more examples because without them I was trying to find a black cat in a dark room.

After spending a certain number of days on arguments with the client, I finally managed to convince him that I needed at least a hundred examples on which I could check the quality of the search. After a few more wasted days and nerves, I finally had in my hands the coveted hundred pairs of examples like these:

the real user question -> the corresponding article in the knowledge base

Now I could create something resembling a test dataset to try different models and approaches to searching and evaluate the quality of the results obtained.

To get ahead of myself, I will say right away that I also had to “tweak” the methodology of the “check.” For example, the case where the desired article is not in first place but in second place is not so bad at all; in third place, of course, it's worse, but still acceptable. As a result, the question arose: how to measure the quality of the search even when having examples in hand? The simplest and most understandable metric for the functional customer turned out to be the percentage of answers that fell into the TOP-4. That is, the correct article is among the first four answers from the search algorithm. Why four? Because by default, in our chatbot interface, the user is presented with four most relevant articles as search results.

However, for developers, such a metric as the percentage of those in TOP-4 is not entirely suitable because if the correct answer is not in 4th place but in 1st, that is clearly better, but we do not see this in our metric (the metric does not change in any way). After playing around for a considerable amount of time with different metrics, we concluded through experimentation that NDCG (Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain) metric is ideal for developers. Its essence is that the higher the correct answer ranks in the search results, the larger the metric. In the end, it turned out like this:

At the very beginning, when we improved the quality of the search by percentages with each new iteration, we used TOP-4

Then, when a more “fine-tuned” scale was needed, we used NDCG to measure the quality of the new version of the search

I will also share one life hack that should be kept in mind when testing and deciding whether to release a new version to production. The test dataset must always include "especially important" questions on which you demonstrate your solution and which your VIP users ask. These "especially important" question-article pairs must be found in 100% of cases, without exception. You will not be forgiven for a situation where you rolled out a new "improved" version of the search in production, and at an important presentation, it failed on a question it had previously answered correctly. Or when the "highest boss" asks their "favorite" question, and the system (after yet another update) cannot find the correct article in the knowledge base for them.

And the last question we encountered is how many test questions are needed to assess quality reasonably well? When should we stop with the test dataset, and the addition of new "question-article" pairs doesn't significantly affect anything? Of course, this greatly depends on the content of the knowledge base, but based on experience with 10,000 articles in the knowledge base, we have about 400 test examples. That is, 4% of the number of articles in the knowledge base. Probably, if you have a thousand articles, you need a little more %, and if you have 100,000, then a little less %. But overall, the order is roughly like this.

Brief conclusion: search using cosine similarity (like any other AI project) should start with the preparation of a test dataset.

2. The problem of comparing articles of different sizes.

So, armed with the test dataset, I confidently began testing one BERT model after another in hopes of finding the one that would give me a 99% result. But to my great surprise, almost all models yielded approximately the same results (well below 50%), and I realized that the problem wasn't with the models, but rather that I was doing something fundamentally wrong.

Since I did not have much experience working with LLM models at that time, I made the most typical mistake that I think 99% of beginner AI programmers make. I took an article from the knowledge base in its entirety, added a title to it, and built the embedding vector directly from all the words in the article. In this form, I placed all the vectors (one for each article) in the database and thought that somehow it would match (or rather be found by the cosine similarity search algorithm) with the user's query; after all, this is AI, it will figure it out on its own. Naive, right? But I think everyone starts this way, one way or another. Then comes the realization that things need to be done differently, namely:

breaking articles into sentences and storing several embedding vectors for one article, searching through them separately

removing "garbage" from the articles that shifts the embeddings in the wrong direction; for example, garbage can be: numbers, special characters, and sometimes even abbreviations and titles

the title and text have different "weights"; furthermore, different paragraphs have different weights; as a rule, the answer to the user's question is contained in the first sentences of the first paragraph, and then come the details that shift the embeddings elsewhere, so experimentally adjust the weights for the title, paragraphs of the article, and other attributes if you have them

Thus, if you are going to implement cosine similarity search, you need to first "normalize" and clean the texts that you are going to search through, and only then search through them. Otherwise, it will turn out that all the articles from the Knowledge Base merge into a single "lump" in the vector space (a sort of average temperature in the hospital), and user queries randomly pull out almost always random articles from this "lump."

Brief conclusion: you need to compare texts of the same size without garbage.

3. The problem of different languages of the article and the user.

After cleaning the data and normalizing the size of the articles, I was able to significantly improve the search results, but the percentage of correct answers was still far from ideal. The search returned about 50% correct answers, while it failed in the other 50% of cases. It was time to delve deeply into the questions and answers, i.e., to start getting acquainted with the client's subject area. Upon closely examining the questions and articles where the search algorithm failed, I found such "bright and prominent" examples:

What the user writes | Corresponding article in the Knowledge Base |

Why is my computer slow? | Troubleshooting system performance issues |

No sound on the laptop | Diagnosing and resolving audio output problems on portable computers |

How can I save my photos? | Data backup and recovery procedure |

The first thing that came to my mind was to create a sort of "synonym dictionary" that A is B. But as a series of experiments showed, nothing good came out of this. Compiling a synonym dictionary is a large and thankless job, which also does not automate well. It was decided to abandon the idea of a "dictionary."

The second idea was - let's fine-tune the model so that it understands that A is B. The idea is good, but we barely "squeezed" 100 examples from the client, while tens of thousands of examples are needed for fine-tuning.

I won't bore the reader with unnecessary details about what happened next, but ultimately everyone came to the conclusion that no other method, except for the "administrative" one, could effectively solve the search task. The administrative method means that typical user questions are added to the Knowledge Base (exactly as the user formulates them in their own language), and the search for the appropriate article is conducted primarily based on them. It is a difficult, thankless job, but it is finite. For each article, two to five typical questions (in the user's language) are required, and then the cosine similarity search algorithm itself understands which user question is closer to which article.

If anyone has a more elegant solution to this issue (how to match business language with user language), please write in the comments, I would be happy to discuss and learn something new.

Adding standard questions certainly improved search results, and we gradually rose to values around 75-80%. But it was still not enough; the client wanted to see >90% correct results in the search.

We had to engage in fine-tuning the model. By the way, the model we ultimately settled on is multilingual-e5-large. It suited our task better than any other model on all parameters.

Life hack - to increase the number of examples for training, you can use any serious model like DeepSeek, OpenAI, Gemini, etc. (I cannot know which model is the best at the time you read this). The most advanced model can generate different variants of "user questions" based on the examples you provide it.

A large and serious model can also label a significant portion of the dataset for training on its own instead of humans. We tried several options for labeling datasets (by humans and by soulless machines), and ultimately settled on the following approach for labeling:

humans label about 20% of the total required test and control datasets using real user queries

then the best model generates the remaining 80% of the test and control data

Brief conclusion: matching user language with business language will have to be done manually, while big LLMs will assist you.

4. The problem of the absence of a suitable article.

The first truly serious challenge turned out to be determining when a user is requesting something that exists in the database and when a user is asking some obviously irrelevant question that is not in the database.

The first thing that comes to mind to determine if an article exists in the database or not is to take and use the absolute value of cosine similarity, for example:

anything greater than 0.5 is considered as “answer found and exists in the database”

anything less than 0.5 is considered as “no answer in the database, the user is asking something irrelevant”

But the functional customer vividly and clearly showed us examples where the cosine similarity of 0.3 fits perfectly with the question, and where an article with a similarity of 0.7 does not correspond at all to what the user asked.

Moreover, it turned out that different BERT models have different cosine similarity values, and to jump ahead, I will say that even for the same model after fine-tuning, the similarity values can vary widely.

Our second hypothesis was the following intuitive assumption. If there is an article or a group of articles that is significantly "closer" to the user's query than other articles in the database, then the answer to the user's question exists in the database. If, however, all articles in the database are more or less "equidistant" from the user's query, then the answer to the user's question is not found in the database.

To test this hypothesis, we created a dataset of several hundred questions for which there are answers in the database and questions that are absent from the database (for example, for the question "Who killed Kennedy?" there is clearly no answer in our database). Next, we obtained search results for each query (TOP 100 articles) and attempted to train different ML models (ultimately settling on simple logistic regression) to understand when the returned numbers (the cosine similarity results of the TOP 100 articles from the database) indicate that the answer exists in the database, and when it does not. The result was partially successful. That is, we were able to fairly accurately identify situations where the question definitely exists in the database (accuracy was over 90%). However, in situations where there was no answer to the question in the database, but the algorithm indicated that there was, this occurred in about 50% of cases (i.e., recall was 50%).

To improve recall, we took historical data of what users actually asked, generated additional artificial examples using a large non-standard GPT model, and created a dataset for further training the model on the topic of "the question is not for the database".

As a result, we settled on a somewhat controversial solution (which we will definitely improve in the future), and a "clarify" flag appeared in our system, indicating that the user's question is "not clear" and the user should be asked again, "Your question is not clear, please rephrase it." This flag is "raised" when the model indicates that the question is unclear and the user needs to be asked what they mean.

Practical operation has shown that the first time users are more or less willing to rephrase their request and we receive a more or less adequate request. But! If the situation repeats and we write to the second, third user, etc. “Your question is unclear…” the user begins to get furious and it becomes impossible to achieve anything adequate. After analyzing real dialogues, we decided to ask the user a clarifying question exactly once, and on the second occasion, we would respond with an article found in the knowledge base.

For those who noticed a logical problem here, that in fact these are two different tasks:

The article is not in the knowledge base

The article exists but the user's question is unclear

Five points for attentiveness. Yes, we consciously decided to solve this problem in this way because separating these two scenarios would require significantly more engineering effort than we could afford. Perhaps in the future we will come up with a way to separate these two scenarios without spending human-months on research. If you have thoughts or articles on how to do this quickly and simply, I would appreciate your feedback.

Brief conclusion: The situation where the answer to the user's question is absent in the knowledge base should be resolved through a clarifying question and further training of the model on examples when it is necessary to clarify the question.

5. The problem of switching to an operator

The option when there is no article in the knowledge base answering the user's question is handled such that we ask the user to rephrase the question once, and then switch to an operator if the model still cannot understand the question. But this is not the only scenario for switching to an operator; our functional client also wanted the following scenarios for switching to an operator:

When the user explicitly says “call the operator.” The problem was that the user could do this in various elaborate ways, for example with the phrase “let me talk to the soulless metal bag.”

When the user writes something negative. In the Russian language, there are countless ways to express negativity.

When the user starts conversations on obviously off-topic (for example, political) subjects.

I won't bore the reader with all the paths we have taken, making numerous mistakes and wasting a lot of time in vain; I will immediately present our current solution here.

The "call operator" check consists of several parts:

To identify profanity and insults, we use classic NLU based on a list of swear words of the great and mighty language.

To identify phrases like "call the leather bag," we use the same fine-tuned e5-multilingual model that determines the "topic" in the same way, based on typical user questions just like searching through the knowledge base (KB). That is, essentially, we have created another virtual article in the KB with typical user questions on the topic of "call operator."

To identify off-topic subjects, we use the K-nearest neighbors method, i.e., we load all our KB and all possible off-topic subjects that a user might theoretically ask (some large GPT can help you generate options) and then see which request is closest to the user's query.

If the user enters an "infinite loop" and keeps asking the same thing, we switch them to an operator on the third time.

It is not an ideal solution, but sufficient to be deployed in production. The markup of real user dialogues showed that the balanced accuracy of the operator-switching functionality with this approach is 96%, which is quite good. I will immediately answer the question of how we measured balanced accuracy. There were two classes: "requires switching to an operator" and "does not require." The imbalance between them is 1 to 9. We sent all user dialogues for a month (several thousand) to the sample. For the business, there is little difference in having one extra operator connected or not switching when it isn't necessary, so the classes are equally weighted.

However, I want to point out that your company's policy on switching users to an operator can significantly affect what functionality you will ultimately program. As a rule, any company strives to minimize the number of operators simply because it is expensive.

Brief conclusion: From the very beginning, discuss the rules for switching to an operator with the business and review real user dialogues to understand when an operator is needed.

6. The Problem of Getting Feedback

After we created the validation datasets, we were able to measure the quality of the search and it seemed that the quality issue was resolved. However, we are creating a product primarily for the end consumer, so it makes sense to also measure the quality of the search from the consumer's perspective. For this purpose, a bunch of metrics have been invented long ago, such as DAU, WAU, MAU, Retention rate, etc. I won't dwell on them here; the goal of this article is specifically the nuances of search in the knowledge base.

So, regarding the specifics of the search. The simplest and most logical indicator at the initial stage seemed to us to be collecting user feedback on the search results. For example, "five stars," or "thumbs up, thumbs down." But! As it turned out, this way the user evaluates primarily their overall impression of the product, not the quality of the search. That is, roughly speaking, the user gives one star because:

- there is no article in the knowledge base that answers the user's question

- the article in the knowledge base is written in a confusing way, even though the search found everything correctly

- the article is correct, but it displayed incorrectly in the user interface

and a million other cases where the search worked correctly, but the user still gave a "thumbs down."

I'm not saying that such an assessment by the user in the interface is absolutely useless, but it's not something to rely on. We searched for a long time for a way to measure the quality of the search from the user's side without putting too much strain on the user, but in the end, we didn't find any silver bullet and currently measure several indicators that are specific to search:

Use of profanity - surprisingly, if a person cannot find what they were looking for, they often start swearing directly in the chat, and this is a good indicator that the search is not working correctly.

Proportion of users who called an operator - there is also a direct correlation between the number of calls to an operator and the absence of a response to the user's question.

Clicks on links in the article - if a person found the correct article, they read it and then click on links, taking some actions.

At the moment, we have not found any direct or indirect metrics that can measure the quality of search in the knowledge base automatically. If you have ideas or experience implementing something similar, please share in the comments - we can discuss.

As a result, the most reliable way to evaluate search quality has become the old good manual annotation of data based on real user dialogues. With random samples, confidence intervals, protein annotators, and experts for validating cases when regular user annotations do not match, etc. I won't go into more detail, as this is a topic for a separate article, but if anyone wants to know the details, write in the comments, and I will write a separate article on how to properly do manual annotation of real user dialogues to assess the quality of AI performance.

Brief conclusion: the quality of search can only be realistically evaluated manually; other automatic methods can only indirectly indicate how well the functionality of the search in the KB works correctly.

7. The problem of duplicate articles

Even during the testing phase of our solution with the focus group, we (as always unexpectedly) discovered that articles in the knowledge base often duplicate each other. This is logically understandable: when the knowledge base is large and filled by many administrators/editors, situations inevitably arise where duplicate articles appear. Moreover, the duplicates can be of several types:

a similar article intended to replace an old one, but the old one was not found (for some reason), resulting in two almost identical articles in the KB

a more detailed article, for example, if you already have an article “how to format a hard drive,” and an editor added an article “how to format a drive on Mac”

and the reverse situation, where there are several specific articles and a new summarizing article is added

Moreover, if you are directly engaged in the functionality of searching the knowledge base right here and now, it means that the editors did not have a tool that would help them discover (with the help of a yet non-existent quality search) a similar article, and instead of browsing through hundreds or even thousands of articles, the editor decides that it is much easier and faster to write a new one. The editor thinks: “Well, who cares, there will be two instead of one.” And regarding the fact that the end user’s brain explodes when they see two practically identical articles in the search results, the editor thinks about that last.

The only effective way to avoid duplicates is to create a separate tool that regularly (monthly, upon adding/editing an article, etc.) checks the entire knowledge base for similar articles and issues a warning to the editor (or outright prohibits editing) about the presence of a similar article.

Fortunately, this turned out to be a relatively simple task considering that the search of the knowledge base was already ready. We took our current algorithm for searching articles; if the distance between two articles was less than a certain threshold (which we constantly changed within the range of 0.3 to 0.1), we displayed the articles as duplicates.

The team required only two things:

To carry out the initial cleanup of the " Augean stables" of the knowledge base from duplicates. This can and should be done in a semi-manual mode, with the selection of coefficients.

Create a separate tool that will regularly monitor the emergence of new duplicates and inform about them.

Overall, this is more administrative work, but it needs to be done BEFORE launching into production; otherwise, you will have to deal with cleaning up duplicates in emergency mode, receiving a lot of negativity from your users for no reason.

Brief conclusion: at least 50% of your success depends on the quality of articles in the knowledge base, don’t be lazy and create a separate tool for editors and, together with them, preemptively clean the knowledge base of duplicates.

Write comment