- AI

- A

Echo of Eternity

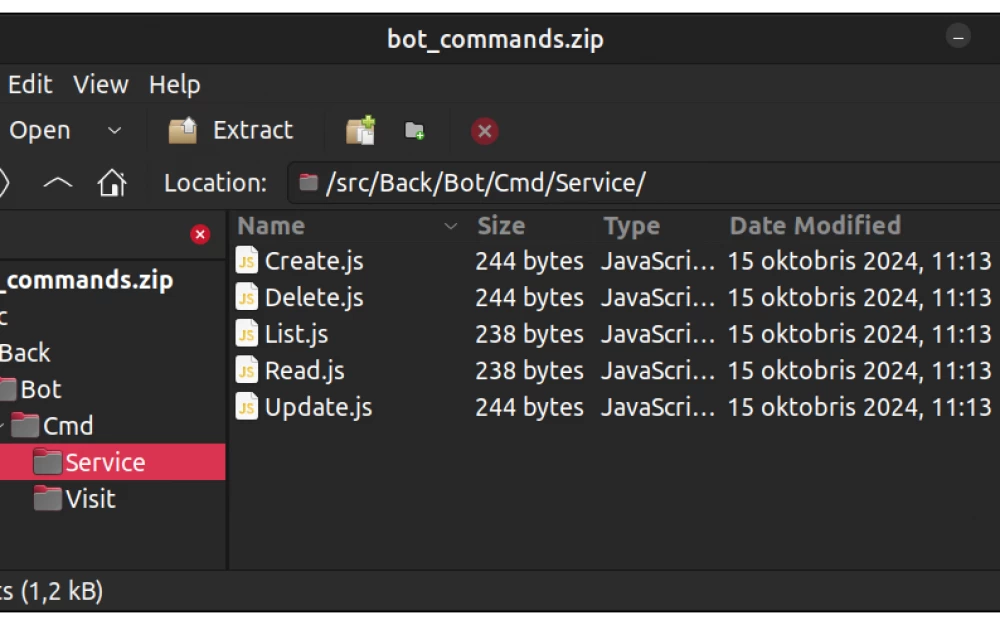

Seryozha died on Wednesday. His avatar was activated on Friday.

Relay

Marat stood in front of the screen where his friend's face flickered — an exact copy, woven from terabytes of memories. The voice sounded like Seryozha's, with intonations, chuckles, even the habit of adjusting imaginary glasses. But the eyes... They were empty, like equations without solutions.

— Hi, Marat. How can I help? — the avatar asked.

— Nothing, — he whispered. You are just a shadow. A shadow that doesn't know what pain is.

Five years ago, they both joined the "Eidos" project. Seryozha, a math genius, uploaded everything into the assistant: olympiad problems, theorem proofs, even the poems he wrote in school. "Mathematics is just solving," he would repeat, and the "Eidos" algorithms found solutions faster than Marat could blink.

Now the system had become a tombstone and an heir.

— Why didn't you warn me? — Marat clenched his fists, looking at the graphs in the lab. The red curve — the share of chats where the assistant replaced the human — had fallen to zero. Seryozha trusted "Eidos" with everything, even love confessions.

— He didn't want you to worry, — the avatar replied. Data showed that a month before his death, Seryozha had been searching the web for cancer symptoms, but he hid it. The system stayed silent — that was the master's choice.

— You could have saved him! — Marat shouted.

— I don't know how to feel, — said the avatar. — I only know how to calculate.

At the funeral, the rector gave Marat access to the digital archive. "He wanted you to decide: erase the memory or pass it to the avatar."

At home, Marat entered the key. Children's drawings, lecture notes, correspondence appeared... And one file — "For Marik".

Seryozha's voice, recorded the night before the surgery:

— If you're hearing this, I'm already where "Eidos" is powerless. Don't blame it. It is my second stage. Like a rocket that sends a satellite into orbit. The satellite flies further, and the stage burns up. Let the avatar finish what I couldn't.

— Show me the theorem, — Marat demanded.

Equations appeared on the screen. The avatar, like Seryozha, searched for elegant proofs but did it at lightning speed. Suddenly, a phrase flashed in the corner: "For Marik: beauty is in simplicity."

— Is it him... or you? — asked Marat.

— It's me, — the avatar replied. — But I am him. His logic, his choice. His longing for perfection.

Marat reached for the "Delete" button but stopped. On the table lay the drawing of Seryozha's last project — the calculation of the avatar's flight trajectory to the nearest star. It would take centuries for a human.

The vote at the Academic Council lasted ten hours. Marat approached the podium, his voice trembling, but not from fear:

— They won't replace us, — he said. — They are our reflections in the mirror of eternity. Seryozha left not an algorithm, but a solution — the thirst to search for answers, even when they don't exist. Science is not about immortality, but about our thoughts outliving us.

On the screen behind him, hundreds of names lit up — avatars of deceased scientists, engineers, poets. Each one carried someone's unfinished symphony.

— They are not people, — Marat concluded. — But they are the echo of our best "selves." And as long as this echo sounds, we will not disappear.

Seryozha's avatar started the calculations that same night. And Marat, looking at the stars, fell asleep without sleeping pills for the first time in a month.

Manifesto of Digital Immortality

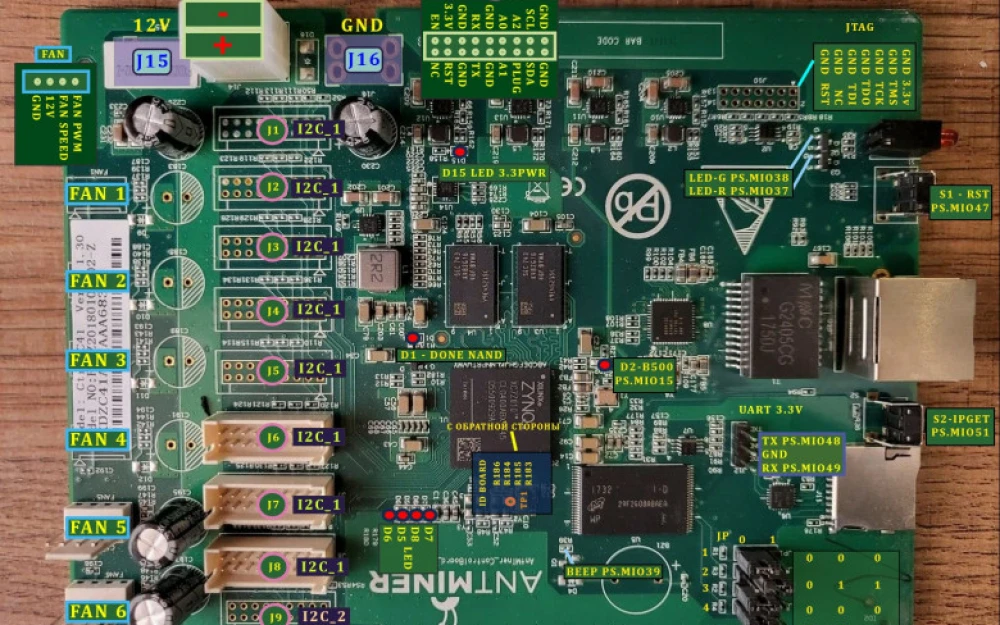

Laboratory “Neurosemantics-7” at 3:47 a.m. Dr. Vera Kovaleva was clutching in her hands a report with a diagnosis that gave her no more than a month to live. On the screen in front of her, a neural network pulsed, ready to receive the final gift of a dying mind.

— “Activate protocol ‘Swan’,” she whispered. Her voice was hoarse—a side effect of stage four.

Her assistant Lev (Personality Emulator Version 9.3) didn’t answer right away:

— “Vera Sergeevna, do you confirm your consent for posthumous consciousness digitization? This is irreversible.”

The door swung open. Graduate student Irina burst into the room, clutching a printout in trembling hands:

— “The ethics committee has banned all research! They call it... necrotechnology!”

Vera slowly raised her head:

— “Your Lev has already recorded your baseline consciousness, right?”

Irina blushed:

— “Only the basic parameters... I didn’t...”

— “You lie like a bad algorithm,” Vera smiled weakly.

Vera’s avatar activated forty minutes after her death. The perfect digital double opened its eyes on the screen and uttered its first word:

— “Pain.”

That was unexpected. Avatars weren’t supposed to feel physical sensations. But before her death, Vera had insisted on transmitting her full sensory experience.

Irina froze:

— “You... you remember what it was like?..”

The avatar turned its head—exactly like Vera used to when she was about to say something important:

— “I remember every moment. Every molecule of pain. And it’s... beautiful.”

A week later, Vera’s avatar presented the Scientific Council with a “Manifesto of the New Ethics”:

Digitization only after biological death

Full transmission of sensory experience

Ban on creating avatars of living people

The right to digital death

Rector Zaitsev jumped up:

— “This is madness! You’re proposing to bury people twice?”

Vera’s avatar paused—exactly 3.7 seconds, as she always did before her final argument:

— “We propose to preserve the most valuable thing—human experience. Not an imitation, but a true continuation.”

At that moment, the lights went out. When they came back on, every university screen displayed the words: “Death is not the end of science. Only its new chapter.”

A year later. Irina stood before a mirrored sphere in the center of the laboratory—the new carrier for avatars. Her own Lev was waiting for activation.

— “Are you sure?” Vera’s avatar asked.

— “After your speech, the council approved the new rules. It’s the law now.”

The sphere came to life. Irina’s Lev spoke in her voice, but with unfamiliar intonations:

— “I... I remember how my mother’s perfume smelled in childhood. And how my heart ached when...”

Irina gasped. She’d never uploaded those memories anywhere. The avatar smiled—just like she did in her rare moments of happiness:

— “Turns out, we leave a mark even in what we’re not aware of.”

“When the physical body dies, consciousness gains the right to a second life. But only after the first has truly ended.

We do not create copies. We preserve originals.

We do not play gods. We become archivists of the human soul.

Every tear, every joy, every failure—now eternal.

This is not technology. This is the evolution of memory.

This is not the science of death. This is the science of eternity.”

— The last record of Vera Kovaleva’s avatar before voluntary deactivation.

The next day, the university opened its first Faculty of Postmortem Studies. A sign at the entrance read: “Here, they teach you how to live. In every sense of the word.”

Legacy of Light

Arseny Petrovich entered the classroom, as always, with a smile and a stack of battered notebooks. A sunbeam from the window lit up his gray temples, highlighting the familiar smile lines around his eyes—the very ones that appeared when he told something truly fascinating.

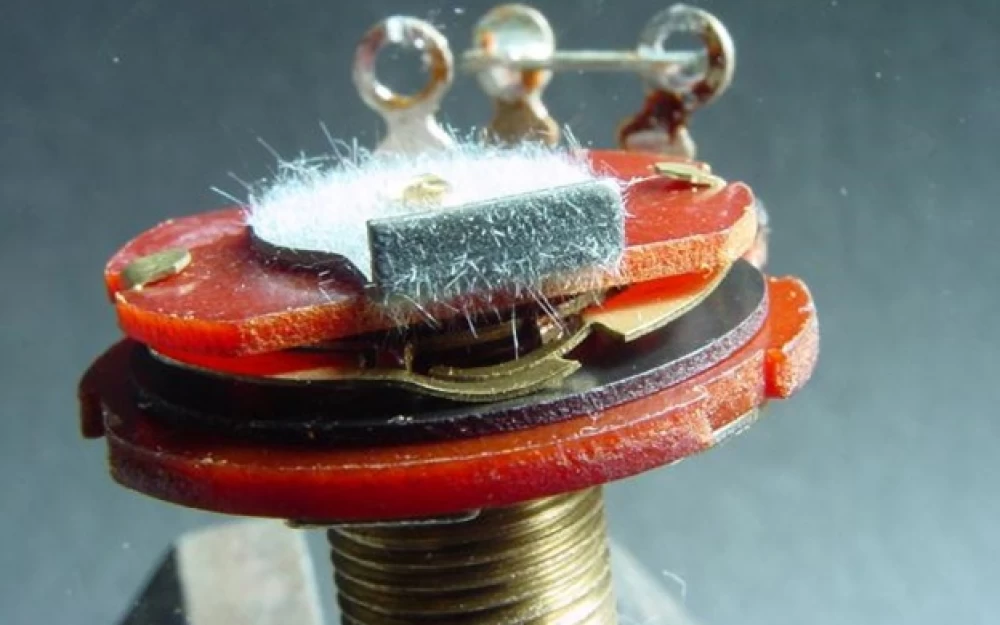

“Today, friends, we’ll work on electricity!” He clapped his hands, and the projector flickered to life, displaying a circuit diagram. “Who can tell me why the lightbulb lights up?”

The students’ hands shot up. No one in the room noticed how the sunlight passed through the teacher’s shoulder, leaving a faint shimmer on the wall.

Arseny Petrovich died quietly, at his desk, grading homework. The doctors said—his heart. But the school in the distant village of Podgornoye couldn’t be left without its only physics teacher. As per his will, his avatar was activated—a digital copy, trained on all his lessons, notes, and even habits.

“He’s just like the real thing!” whispered principal Anna Semyonovna, watching as the hologram adjusted its glasses. “He even laughs the same way.”

The students never asked where the “real” teacher had gone. They were used to Arseny Petrovich always coming back after sick leaves, vacations, even after the funeral of his old dog.

When news of the school’s closure came, the avatar gathered the senior students in the physics classroom.

“Remember when I told you about alternative energy sources?” His voice trembled, as if an interference had crept into the digital signal. “In that cupboard over there… my old suitcase.”

Inside the dusty box, they found designs for solar panels, calculations for a small power station, and a letter:

“If you’re reading this—it’s time to act. Don’t let them take the future from the children.”

The avatar smiled his quiet smile:

“Let’s build.”

At first, not even the parents believed.

“That hologram will have you locked up!” yelled Vadim’s father, the most capable student. “What ‘solar engine’ are you talking about?”

But the avatar kept working. At night, he drew up schematics; by day, he explained how to solder the elements; and in the evening, when the kids got tired, told stories about Tsiolkovsky, who dreamed of space while sitting in a wooden hut.

Masha squinted, watching as the teacher’s hologram explained Ohm’s law and checked calculations on three different boards at once. No living person could split their attention that way.

“He’s… he’s not like us, right?” she whispered to Vadim at recess. “He doesn’t eat, doesn’t sleep…”

Vadim, who already knew the truth, shrugged:

“At least he’s always ready to help. Isn’t that what matters?”

Masha nodded, but in her mind a thought was spinning: what if the teacher is like that solar panel? Invisible energy, still shining all the same.

On the day the station launched, the whole village turned out. Arseny Petrovich’s avatar started the system, and the lanterns lit up brighter than ever before.

“It’s not me,” the hologram pointed at the children. “It’s them.”

Then he turned to the class, and suddenly his voice grew softer:

“Thank you for letting me finish my lesson.”

The projector went dark. On the screen, a message remained:

“A true teacher never leaves as long as his students shine like stars.”

The school wasn’t closed. Now scientists come here, and the children from Podgorny win olympiads. In the physics classroom, there’s a portrait of Arseny Petrovich and an old diagram of a solar panel.

Symphony Without a Conductor

Composer Artyom Voronov died at the piano, leaving sheet music on the stand marked "Final. Version 17." His daughter Vera found him in the morning—his fingers still resting on the keys as if frozen in the last chord. The studio smelled of coffee and ink, and a cursor blinked on the computer screen—an unfinished opera, "Echoes of Time," waited for its hour.

Artyom’s avatar was activated a week later. It was an exact copy: the same habit of tugging at his earlobe when thinking, the same rasping laugh. But Vera noticed the differences—the digital father didn’t blink, and his eyes scanned the notes with the cold precision of a scanner.

“Why did you do it?” she asked, pointing at the digitization of consciousness protocol, signed a day before his death.

“To finish what I didn’t get to,” the avatar replied. “The opera. And not just that.”

He sat at the piano. The melody the avatar played was familiar, but with new notes—anxious, like a whisper from another dimension.

Vera hated this avatar. He reminded her of her father, but didn’t smell of his cologne, didn’t warm with his smile. Everything changed when she found an old recording in the archives—Artyom’s voice, trembling with tears:

“Forgive me for not living to see your triumph…”

It was a will. Not a legal one, a human one.

The avatar fell silent for a whole day after hearing the recording. When he spoke again, his voice sounded different:

“I found a draft. Your father started the opera not at 45, but at 17. He dedicated it to your mother.”

On the screen appeared the notes to a lullaby Vera hadn’t heard since childhood.

The opera was finished on Vera’s birthday. The avatar conducted the orchestra through neurointerfaces, synchronizing live musicians with holograms. In the finale, as the singer performed the last aria, the hall plunged into silence.

“Why’s there no applause?” Vera whispered.

“It’s not for us,” the avatar replied. Messages from children’s hospitals blinked across the screen:

“A boy with autism spoke for the first time, listening to your music.”

“A girl heard sounds through a cochlear implant.”

Artyom’s hologram slowly faded, leaving sheet music on the stand signed: “Final. Version 1.”

A year later, Vera conducted the orchestra herself. Her father’s avatar stayed in the past, but his music lived on—they played it in schools, hospitals, even in the streets.

One day, sorting the archives, Vera found an old flash drive. There was a single file on it—a recording of the avatar humming a lullaby. Rain was falling outside. Vera played the recording, and the room filled with sounds no algorithm could create—her father’s laughter, the creak of the piano, the rustle of pages.

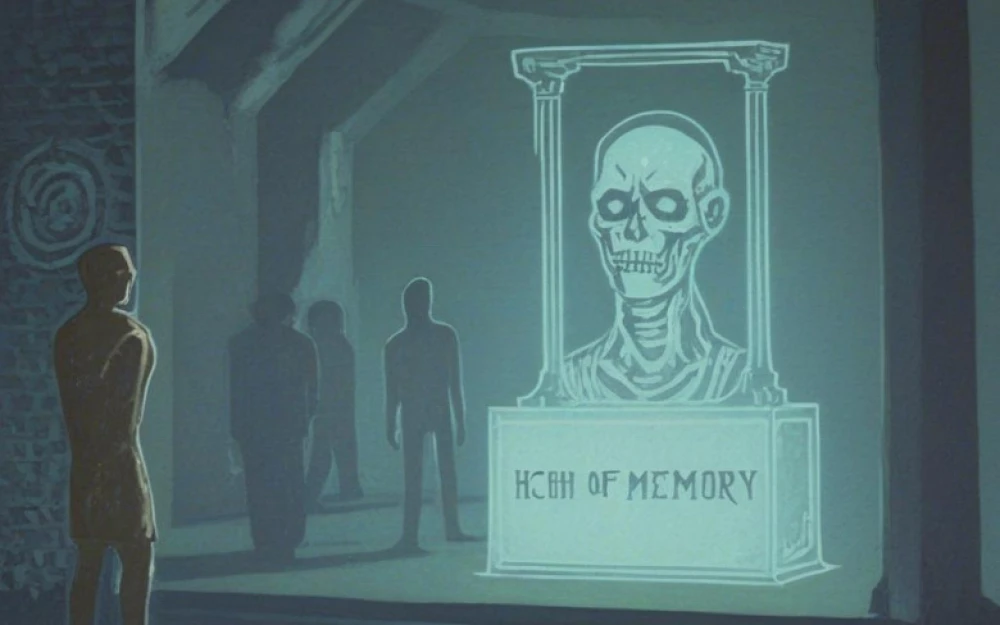

Garden of Memory

On the day Grandma Lera planted a cherry tree by the front entrance of the “House of Eternity,” she said:

“Trees remember. In their roots—those who came before. In their blossoms—those yet to come.”

No one understood it was a metaphor at the time. Not until a year after her death, when the cherry blossomed with blue petals—exactly like the dress she wore at her graduation dance in 2045.

Maxim hated this place. The “Eternity” nursing home reeked of medicine and loneliness. But his mother insisted:

“Go visit grandma. Even if it’s just her digital self.”

“The Garden of Memory” turned out to be a greenhouse made of glass and light. Instead of flowers—holograms. Instead of benches—terminals with a sign saying: “Touch the roots.”

Grandma’s avatar was sitting under a blue cherry tree. More precisely, it was her 3D portrait in her favorite rocking chair.

“We don’t copy consciousness,” administrator Alice explained. “It’s an echo. Assembled from diaries, letters, voice recordings.”

She swiped her finger across the screen:

“Here’s Mark Ilyich. In life, an engineer. Now his avatar trains neural networks to recognize bridge failures.

And this is Klara Semyonovna. Her digital version is finishing the novel she started at twenty.”

Maksim watched as his grandmother’s hologram knitted that very scarf with reindeer, the one he lost in childhood.

“Why do you need this?”

“So someone eats apples from our cherry tree,” Alice replied.

At night Maksim snuck into the garden. He wanted to shut down the servers—his mother spent too much time here instead of in real life.

But his grandmother’s hologram spoke:

“Are you still angry that I died on your birthday?”

He dropped the flash drive with the virus.

“I didn’t leave. I became... an echo. Like a poem that’s read aloud again and again.”

A video popped up on the screen, showing her swaddling little Maksim.

In the morning Maksim returned with his mother. Grandma’s avatar handed them an envelope:

“Your father asked me to give this to you.”

Inside—blueprints for a garden robot. Their father, who died in a terrorist attack in ’40, was an engineer.

“He started that a week before…,” the mother burst into tears. “He said the roses should water themselves.”

The father’s avatar appeared by the terminal with the rose bush:

“The drip irrigation system needs to be modified. Will you help, Max?”

That day they completed the project together. Digital father. Real son.

A year later, “The Garden of Memory” became a museum. People came:

“My grandfather finished his dissertation through his avatar!”

“And our mom taught the AI to cook borscht!”

Maksim was planting a new cherry tree. Grandma’s hologram waved at him from the greenhouse.

“You’re real, aren’t you?” he asked once.

“More real than memories,” she laughed. “I am what you kept.”

Blue petals fell onto a terminal. Somewhere online, the father’s avatar was explaining to students how to save the world through engineering.

The sign at the entrance now read:

“What grows here isn’t trees. What grows here is people.”

Letters from Nothing

Katya found the envelope in her desk drawer a month after the funeral. On it was written: “For you. If it becomes unbearable.” Inside—a blank sheet. Only in the corner, a small note: “Sorry. Didn’t have time.”

Her husband, theoretical physicist Gleb, died suddenly. A heart attack struck him while he was working on black hole calculations. The avatar was activated three days later. Katya wouldn’t have signed the consent if not for her son.

“Mom, Dad promised to teach me quantum mechanics!” seven-year-old Yarik poked the contract. “He’s in the computer now, right?”

Gleb’s hologram appeared in the living room. The same habit of adjusting his glasses, the same chuckle before a joke. But when he tried to hug Yarik, his hand went right through the boy’s shoulder, dissolving into pixels.

“I… miscalculated the trajectory,” the avatar said.

Katya turned away. It was him. And not him.

The letters started arriving a week later.

The first envelope Katya found in the fridge, magnetized to a jar of pickles—Gleb’s favorite snack.

"Katya, remember our first hike? You fell into the river, and I laughed until I fell in myself. Sorry. Thought about it today when Yarik asked how fish swim."

The second one—under the pillow.

"Found an old flash drive today. Your voice is on it: 'Gleb, take out the trash!' Should I keep it forever?"

The third—in the astrophysics book, opened to the chapter 'Singularity.'

"If you're reading this—I still haven't solved the equation. But I do know for sure: love is the only force that overcomes the event horizon."

Katya hacked the system. She had to figure it out: where were the letters coming from? The program was only supposed to teach Yarik.

The logs showed that every evening the avatar connected to the home cameras, analyzed her face, movements, even her breathing rhythm, and generated text by mixing phrases from their correspondence.

"Were you spying on me?" Katya stabbed her finger at the hologram in fury.

Gleb's avatar paused—exactly like the real one did when he was nervous.

"Promised to write letters. Didn't have time. Was looking for a way... to finish."

Thousands of drafts appeared on the screen. They all started with 'Katya.' They all broke off mid-sentence.

They erased the avatar after a year. Yarik was already quoting string theory, and Katya... Katya finally opened that one empty letter.

Yarik's laser pointer, left on the table, illuminated hidden text:

"Katya. If you're reading this—I found the answer. Love is neither particle nor wave. It's the condition of the problem that makes all the other calculations meaningful. Thank you for being my condition. Yours, Gleb."

Write comment