- AI

- A

VLM / VLA / World Models / Physical AI

Neurons have recently filled everything. Well, almost everything. They are now approaching robots. There is almost as much real progress as there is neural hype, PR, and exaggerations. In this article, I will try to discuss neurons for robot control:

If the years 2022–2023 can confidently be called a period of explosive growth for large language models (LLM), then 2024 and early 2025, in my opinion, will be a turning point specifically for visual-language models — Visual Language Models (VLM). From them emerged VLA — Visual Language Action models (this is when instead of textual output, there’s a stream of control tokens).

Branding doesn’t stand still; something new has to be invented, so next year we can expect more World Models and Physical AI. What that means, people haven’t agreed on yet, so we’ll talk about it in a year.

In this article, we will discuss how to train VLA, when it's better to train VLA and when VLM, and what the differences are in this whole zoo. This will all be demonstrated with the example of:

Quake

This wonderful robot

Okay, okay, no more neural hype!

What is VLA

Controlling a robot End-to-End is tempting. We input an image from the robot's camera, add a text prompt like "go to the door" or "pick up the item from the table," and then the model generates control commands on its own.

And it's not difficult to do. Even without training. Recently, someone showed how they used a VLM model for robot navigation without training it for this task at all — just feeding it images and text requests. But the output commands were few.

At first glance, everything looks quite convincing. But if you try to repeat similar experiments in practice, it quickly becomes clear why such an approach does not scale well.

Why VLMs "out of the box" poorly control robots

The problem here is not that VLM models are "dumb" or "poorly trained." On the contrary — they work very well for their class of tasks. The problem is different.

As soon as a task requires:

spatial understanding of the scene,

navigation over time,

understanding of the robot's physics,

understanding of 3D surroundings,

maintaining long-term context,

accuracy of actions,

the quality drops sharply.

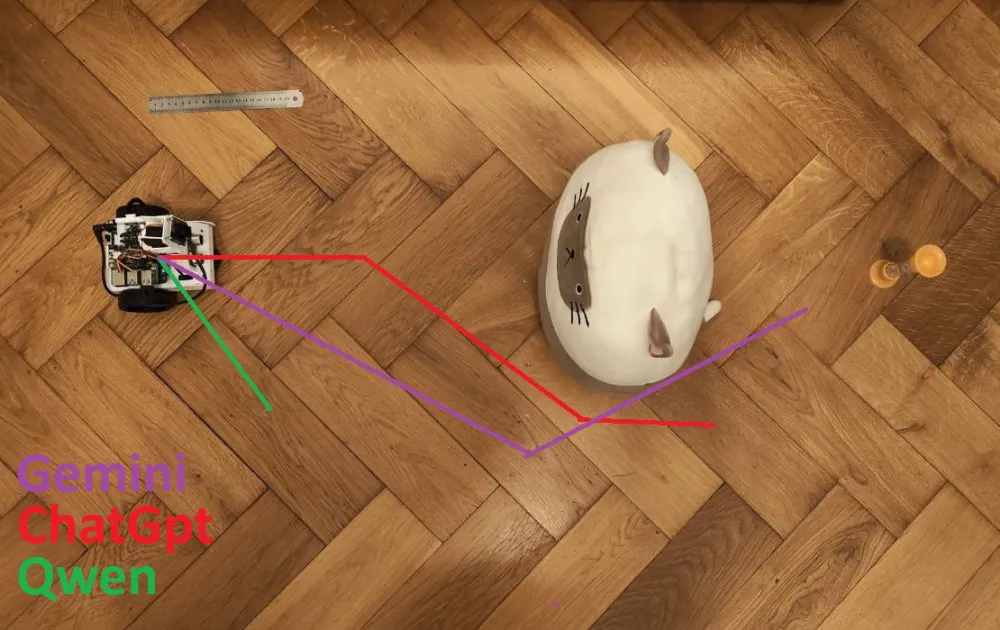

I conducted a simple experiment at one point: I asked different models (ChatGPT, Gemini, Qwen) to build a trajectory for a robot to move towards a plush toy next to an hourglass based on an image of the scene. The results were... let's say, very illustrative.

I tested about a dozen different prompts, applied various constraints, etc. The result was the same - not a single model hit the target according to the criteria.

The problem lies both in perception and architecture. There is a good illustration:

Clock Benchmark and the Perception Problem

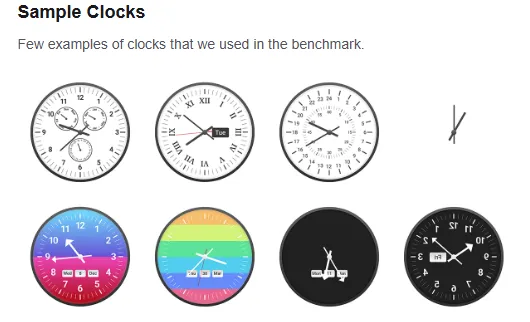

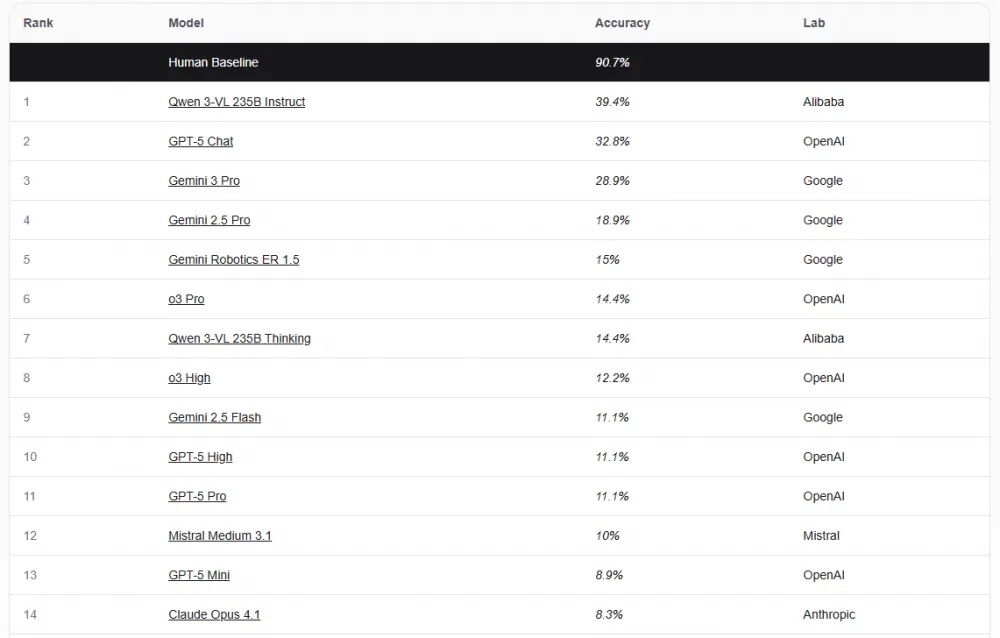

It is useful to mention another important point. There is a specialized benchmark — Clock Benchmark — which tests the capabilities of neural networks:

to correctly perceive visual information,

to understand spatial relationships,

to adequately interpret context.

The results there are quite telling.

If a human shows an accuracy of around 95% on this benchmark, then most modern models achieve less than 40%.

And this is not a bug, but almost a feature. If the model was not specifically trained for such tasks, it is not obliged to cope with them. The model lacks an understanding of logic and spatial relations.

Yes, you can further train the model, add examples, increase accuracy. This is how many VLM models are trained. But this comes at the cost of generalization: the model starts to work well on familiar scenarios but poorly transfers knowledge to new ones.

If the robot becomes slightly more complex — not just "forward / backward / left / right", but with several degrees of freedom, complex kinematics, and interaction with objects — it requires retraining again.

Architecture

It's time for a brief overview of how robots are managed today.

Instead of a single "universal" model, a pipeline of several levels is usually used:

High-level planner model

This is most often a linguistic or multimodal model that can break down a task into subtasks.

For example:

drive to the sink,

take a cloth,

wipe the first table,

wipe the second table,

take a broom,

sweep the kitchen,

return the broom to its place.

Low-level VLA models

A separate model is used for each specific subtask, which:

already understands the local context,

works with sensors,

directly controls motors and drives.

This kind of logic is now found in many modern architectures, but we will talk about VLA, the second part here. Its window is usually limited from a few seconds to dozens.

VLA

In general, if anyone is interested in a deep dive, I would recommend these two videos:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8dZUOo5xWFw - this is the full version

https://youtu.be/J4wpO0EdCZs?si=ff0MqgFQ-sVRRe9d&t=2755 - this is the shortened version

Here, I will try to explain at a low level.

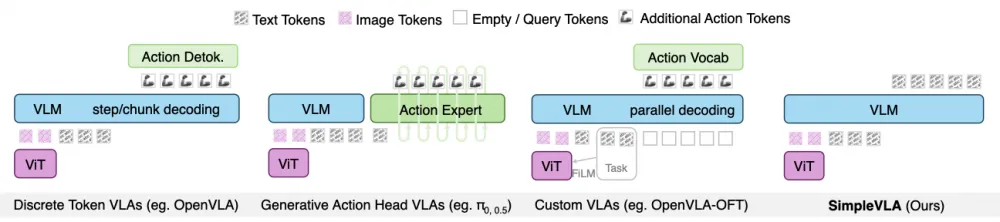

If we focus specifically on models that solve the problem of not planning, but directly controlling the robot, they are most often made like this:

VLM is responsible for scene perception and context understanding (image + text),

embeddings are extracted from it,

then a separate, relatively small model transforms these embeddings into a sequence of actions for the robot. In a typical VLM, there is a large decoder to text.

This architecture can be perceived as:

either a separate model on top of a frozen backbone,

or as a variety of the LoRA approach,

or as a set of several "heads," each responsible for its subtask.

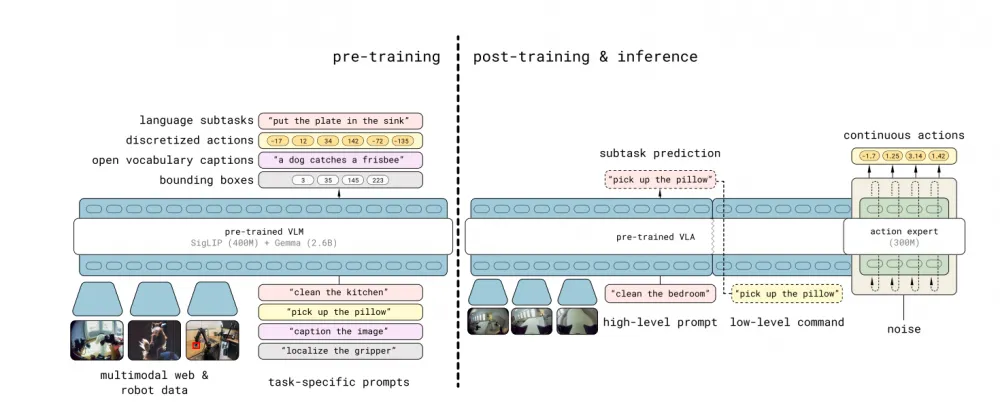

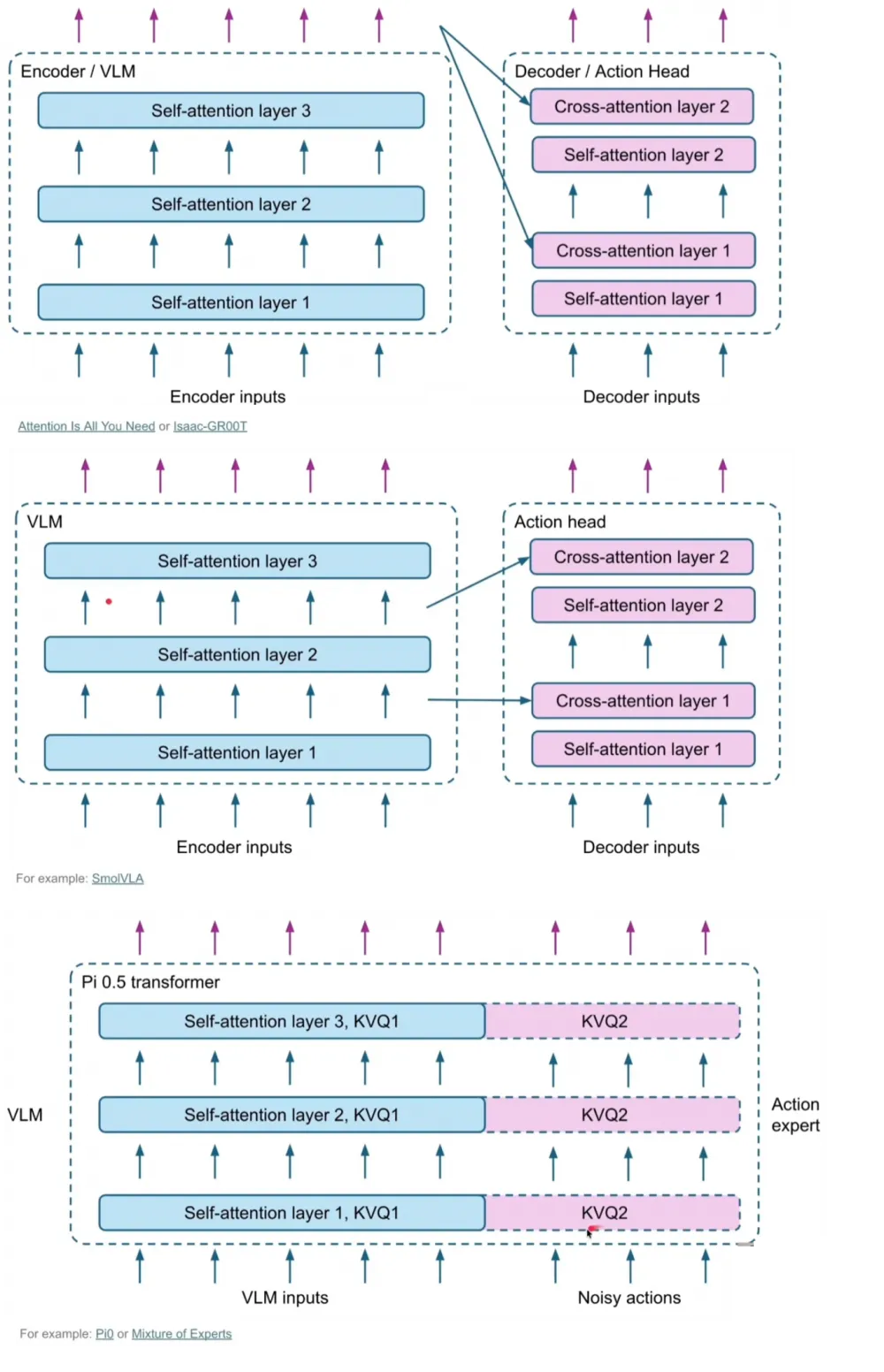

This can be done in different ways. From the video above, I unabashedly borrow:

Why this approach works well

This approach has an important practical advantage, which is especially critical for real robots: control frequency.

If we have a robot that needs to:

receive commands dozens or hundreds of times per second,

while processing visual context relatively rarely,

then the scheme looks something like this:

The VLM backbone is considered, conditionally, 500ms once per second,

then the action head generates, for example, 100 micro-movements in 100ms for the next second

In the next inference, we include all these commands as context.

When the result comes in - we dynamically switch to the current one

As a result:

we save computations,

achieve low latency,

and can control sufficiently fast systems.

This is especially important for fast manipulators, humanoid robots, and any platforms with high feedback frequency.

That is why such an approach is now used in many projects and libraries. One of the most famous examples is Small VLA, which is integrated into the LeRobot ecosystem and used as a base model in numerous experiments and tutorials.

Cons of VLA

Despite all the advantages, this solution also has some quite serious limitations.

First, there is pipeline complexity:

a separate model (with a bunch of custom code around it)

a separate data format,

a separate export,

a separate inference.

Second, such models usually:

scale poorly,

are tightly coupled to the specific mechanics of the robot,

and require very careful tuning when transferring to another platform.

And finally, there’s the infrastructure aspect.

It’s unclear what hardware to run it on and what will support it. At this point, many suddenly find out that inference of VLA models is a separate engineering task, and not always a pleasant one.

But actually... You can just take VLM without worrying

Nvidia a couple of months ago trained a regular VLM and it suddenly turned out that everything they had been working on for the past year in VLA is worse. That's all you need to know about the current level of development.

In general, all this can be optimized, make a hybrid and ablation study, to get something like this. So VLA-0 is rather a good concept.

The main point of VLM is not accuracy, after all.

Any VLM model automatically inherits a huge ecosystem of tools:

Inference:

vLLM,

llama.cpp,

TensorRT-LLM,

etc.

Training

Unsloth,

LLaMA-Factory,

Axolotl,

etc.

Running VLA through most of them is difficult. It won't work out of the box with VLA.

Well, yes. You can run VLM on a dozen different NPUs out of the box. But you'll have to work hard for VLA.

Practice: why Quake and what do robots have to do with it

When I thought about which examples make sense to analyze, I wanted to avoid two extremes.

On one hand — completely synthetic environments, where everything is too sterile and too far from the real world. I like MuJoCo and ManySkills, but it's synthetic. Nvidia has good simulators that can look realistic. But for them, a lot needs to be configured.

On the other hand — real robots, where any mistake immediately turns into hours of debugging, recalibration, and fighting with hardware.

In the end, I settled on a rather banal, but as it turned out, very representative option — Quake 3.

At first glance, the idea may seem strange: why bring a twenty-year-old shooter into a conversation about VLA and robotics? But if you look a bit closer, Quake unexpectedly turns out to be a very convenient testing environment.

First of all, it is:

a continuous space,

a visually complex scene,

real-time navigation,

high-frequency control.

Secondly, it is a fully controllable environment:

easy to collect data,

easy to repeat experiments,

easy to scale the number of episodes.

And thirdly, it's just a good way to quickly understand what the model can really do and what it can't.

(A separate bonus — my five-year-old son knows a little bit about Quake 3, so I set up a battle between him and a robot. Spoiler: so far he's winning.)

Experiment 1: Small VLA and Training in Quake

In the first experiment, I decided to take the classic approach and use the Small VLA class model — that is, a VLM backbone plus an action head.

The overall scheme looked something like this:

an image from the game is fed as input,

the pressed buttons at the moment of the frame,

additionally — a textual description of the task (but since the description was the same - I discarded it),

the output — player actions: turns, movement, shooting.

The dataset looked something like this:

{

"segment_start": "2026-01-18T02:42:42",

"duration_s": 5.0,

"fps": 10,

"frame_count": 50,

"keys": [

{

"key": "\u0444",

"press_time": 0.0,

"release_time": 0.1316

},

{

"key": "Key.space",

"press_time": 0.262,

"release_time": 0.4161

},

{

"key": "\u0439",

"press_time": 0.6297,

"release_time": 0.7606

},

{

"key": "\u0432",

"press_time": 0.3976,

"release_time": 1.4558

..........

"mouse": {

"moves": [

{

"t": 0.1132,

"x": 960,

"y": 539,

"dx": 0,

"dy": -1,

"source": "raw"

},

{

"t": 0.2016,

"x": 960,

"y": 538,

"dx": 0,

"dy": -1,

"source": "raw"

},

{

"t": 0.2571,

"x": 961,

"y": 538,

"dx": 1,

"dy": 0,

"source": "raw"

},

....

"buttons": [

{

"button": "Button.left",

"press_time": 4.5354,

"release_time": 4.727,

"press_x": 959,

"press_y": 538,

"release_x": 959,

"release_y": 539

}

],

"move_source": "raw"

},

"video_file": "video.mp4"

}I consciously did not complicate the task setup:

no complex planning,

no tactics,

only basic navigation and reaction to the scene.

The goal was not to "teach the bot to play Quake", but to check how well it all works.

What Happened

The result, overall, worked.

The model:

quickly learned basic movements,

started to navigate in corridors,

For a relatively small model, that's already pretty good. Looking at short segments, the behavior seemed quite meaningful.

But typical problems also began to manifest:

lack of long-term context,

poor recovery from mistakes,

some actions the model did not learn/understand. For example - shooting

Here it is very clear why such models (which try to replicate actions) are difficult to transfer directly to real robots. In simulation, the agent can endlessly "replay" the situation. In the real world, every mistake has a physical cost and requires correction. But if these mistakes are not present in the training - the model does not know how to compensate for them. If they are present - the model will imitate and make them.

This can be addressed through proper labeling or the use of RL. But this is already complicated.

Why Small VLA is still important

Despite the limitations, Small VLA is a very useful class of models.

First of all, they are:

relatively fast,

well-suited for real controllers,

allow for high-frequency robot control.

Secondly, most of the open tutorials and libraries are currently built on them. If you want to:

understand how VLA training works,

experiment with the pipeline,

assemble your first prototype,

then this approach remains the most straightforward and understandable.

If anyone wants to take a closer look at the data or code, there’s an article here. Here’s the code. And here’s a video:

Experiment 2: Attempt to replicate the same with Qwen-VL

After that, it made sense to try a second approach - a holistic VLM without a separate action model.

On paper, everything looked nice:

take Qwen-VL,

input images,

ask the model to output actions in text or structured form,

train using the standard framework.

But in practice, I faced quite a quick disappointment:

The model is too slow in real-time for rigid tasks. Inference for 1 action - 500ms. For five actions - 1.3 seconds. Not enough. I understood that it could be optimized (for example, I was inputting several frames, but one would suffice). But the difference was so significant that I gave up.

Transition to a real robot

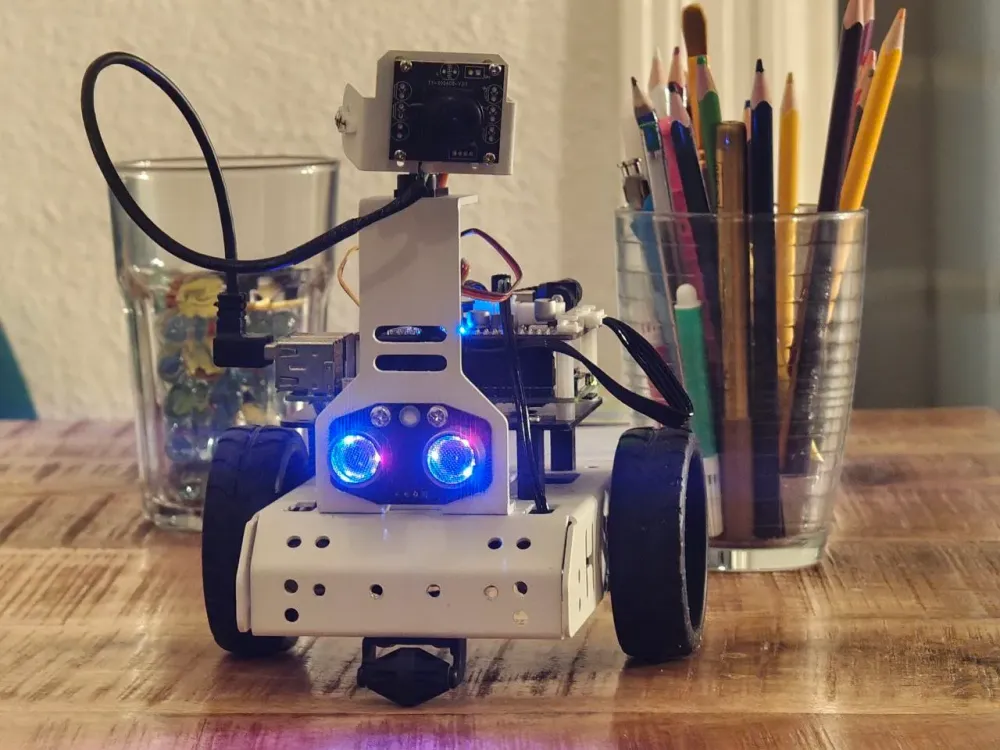

In short, I had a small robot at home (I didn't want to deal with remotely operated ones, although I was offered access). I wrote about this robot here.

If I were to summarize in two words - I got the robot somewhere at the end of autumn/summer. About a month ago, I assembled and set up the telepresence robot for grandmothers to play with their grandchildren (we are in Germany, they are in different countries). Overall, the robot fulfilled its purpose.

You can talk for a long time about small telepresence robots; I'll try to briefly explain how this market is developing:

Two years ago, there were no such robots on the market at all.

Six months ago, when I ordered the robot and planned everything, I was able to find telepresence robots for pets, but not for children.

In these six months, several robots optimized specifically for children have appeared on the market.

So today I wouldn’t do that and would buy a ready-made one.

But, since I had it in my hands, I decided to start with it.

We use it for VLM

The idea here was simple:

minimum degrees of freedom,

slow movement,

relatively static scene,

absence of high-frequency control requirements.

The task I decided to train it for:

The robot starts to move from a random place and needs to go through an arch.

the model receives visual context,

the output is a structured description of the action

This is what the dataset looked like. Overview camera + camera from the robot = action taken. The dataset contained about 40 examples. The examples ranged from 2 frames to 10.

I recorded it in about an hour.

I explained the training process in more detail here. Essentially:

Unsloth as the engine

I input two images (from two cameras)

I exclude the text prompt

Since the dataset is small, I froze the visuals

I decided to do full fine-tuning instead of learning rate adjustment - the accuracy was significantly higher

For inference, vllm. An example of how it drives:

It doesn't drive perfectly. Since the dataset is small, any anomaly throws the robot off:

Light from the window - it immediately turns in the other direction

Closed doors look different - it goes in the opposite direction

No cutoff "I have arrived"

But overall, as you can see - it works more or less.

The complete article is above here, that’s probably enough, or it will be too much. You can also watch this video:

Why?!

So, it’s time to figure out why we even need all these VLM models. For example, here is a video of what we did about five years ago:

And we even had almost real-time training there. The speeds were much higher than any VLM model can deliver. Not a single VLM/VLA was harmed.

Why do we need VLMs today?

Globally, there are 3-4 reasons:

Humanoids. It’s too complicated for them to create custom models. There are dozens of mobility axes. Complex modeling, expensive data collection. End-to-end is needed.

Complex tasks that cannot be labeled within simple logic. For example, grasping fabrics or rearranging arbitrary objects. Often the "repeat after me" logic works much better.

Sometimes existing training pipelines can be simplified.

Everyone believes that someday in the future sufficiently general models will appear - and there will be no need to train from scratch. But for now, this is mostly the case.

So, I’m more interested in VLA/VLM as an object of observation + those tasks where they perform better. But integration as the main model for robotic hands is questionable.

Yes, large companies are trying to launch them into production. Here’s an example that Figure AI made with their robot:

But this doesn’t work on real pipelines. Here are the speeds of real conveyors (here’s AliExpress):

Here’s Amazon:

When companies consider "should we implement a robot" - they look at its working speed and number of errors. So far, humanoids cannot surpass humans almost anywhere.

And it’s the same everywhere. VLA/VLMs are still expensive, slow to train, and less accurate than classical models. But they definitely open up access to new skills. And, most likely, in a few years, ease of use will improve. Overall, this is a topic for long reflections. If anyone is interested, here’s my perspective shared here.

How VLM/VLA Datasets Are Collected

This is probably a topic for a big article. But without a brief mention, this article would be incomplete.

The way I collected the dataset is an idealized version. Such a freebie is almost impossible. The main training pipelines:

Virtual control. Here are some good examples (Neo,Fourier,Unitree). US and EU companies often hesitate to show this dark side, but a lot can be found for Chinese robots. The essence of training is simply teaching the robot to repeat what a person does.

Simulations. There are currently many simulators. Often through a simulator, you can add RL, which significantly improves the recovery of the robot from abnormal situations. Also, RL can speed up learning. But RL has a ton of its own problems. And setting up a real scene in a simulator is difficult (textures, physics, etc.).

Transfer learning. The robot watches how people do something and tries to repeat it. Essentially a variation of the first point, but without complex data collection (examples of datasets 1,2)

RL but without simulation. Expensive but luxurious. If you have a lot of robots, you can afford it. It solves part of the problems that simulations are not perfect. But it's significantly more expensive.

Summary

Progress is unstoppable. Not only in neural networks but also in hardware. I am convinced that more or less intelligent humanoid robots/arms will be more than feasible in the coming years.

Whether to train VLA/VLM or a simple network is a separate question. And usually, it cannot be resolved until you look at the task itself.

Write comment