- Security

- A

Hacking a 40-Year-Old Copy Protection Dongle

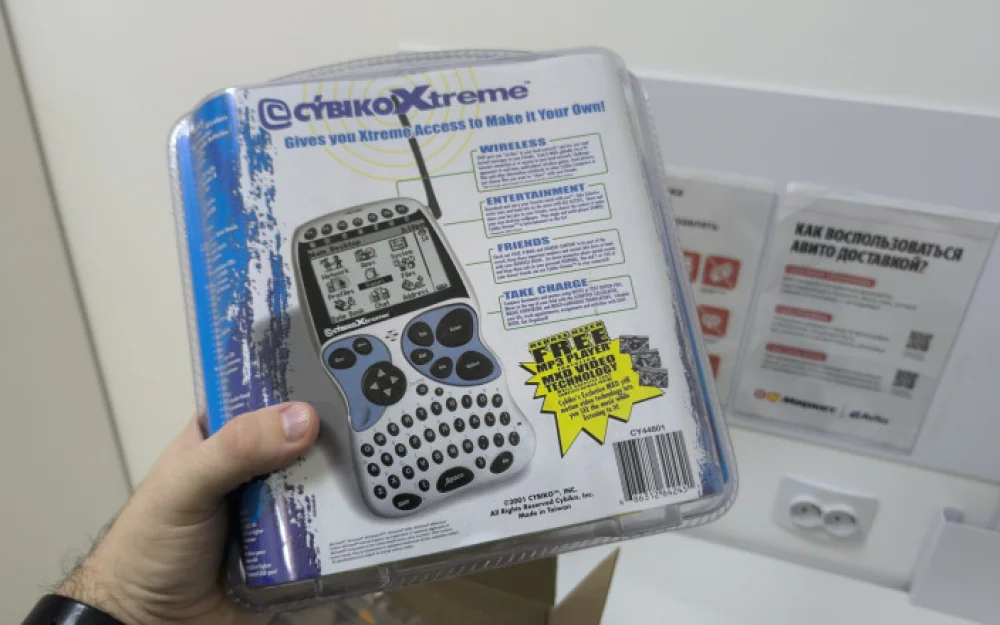

That's right - this little device stood between me and the ability to run even older software that I unearthed during my process of software archaeology.

Recently, I helped a friend's accounting firm migrate from an extremely outdated software package that they had been forced to use for the past four decades.

This software was written in the programming language RPG (Report Program Generator), which is older than COBOL (!); it was used on mid-range IBM computers like the System/3, System/32, and up to the AS/400. It seems that RPG was later ported to MS-DOS, so the same programs written in RPG could run on personal computers. That's how the firm ended up in this situation.

This accounting firm was operating on a Windows 98 computer (yes, in 2026) and running RPG software in a DOS console window. It turned out that the software required a special hardware copy protection dongle to be connected to the computer's parallel port! In those days, this was quite a common practice, especially among suppliers of "enterprise" software who protected their very important™ programs from unauthorized use.

Unfortunately, most of the text and markings on the dongle's label have already worn off, but we have a few clues:

The words "Stamford, CT" and, most likely, the logo of the company "Software Security Inc." The only evidence of this company's existence is an article about the demonstration of its products at SIGGRAPH conferences in the early 1990s, as well as numerous patents related to software protection.

A word that looks like "RUNTIME," which can barely be made out.

First, I created a disk image of the PC with Windows 98 on which this software ran and launched it in an emulator to see what the software does and likely export data from it into a more modern format for use in current accounting programs. But, of course, all of this requires the hardware dongle; it seems that none of the accounting tools worked without it being connected.

Before starting to work, I searched the disk image for any interesting clues and found a lot of curious (and archaeologically valuable?) items:

We have a compiler for the RPG II language (great!), created by Software West Inc.

Moreover, the disk contains two versions of the RPG II compiler released in the 1990s by the same Software West.

There is the complete source code of accounting software written in RPG. It seems that the complete accounting package consists of many RPG modules managed by DOS batch files; all of this is organized into a "menu" system through which the user navigates by entering numeric combinations. It is clear that the author of this accounting system originally programmed IBM mainframes and firmly decided to transfer their skills to DOS, but the result turned out to be controversial.

I began isolated experiments with the RPG compiler and quickly realized that a hardware dongle is required by the RPG compiler itself, which automatically injects the same copy protection logic into all executables it generates. This explains the (presumed) "RUNTIME" inscription on the dongle.

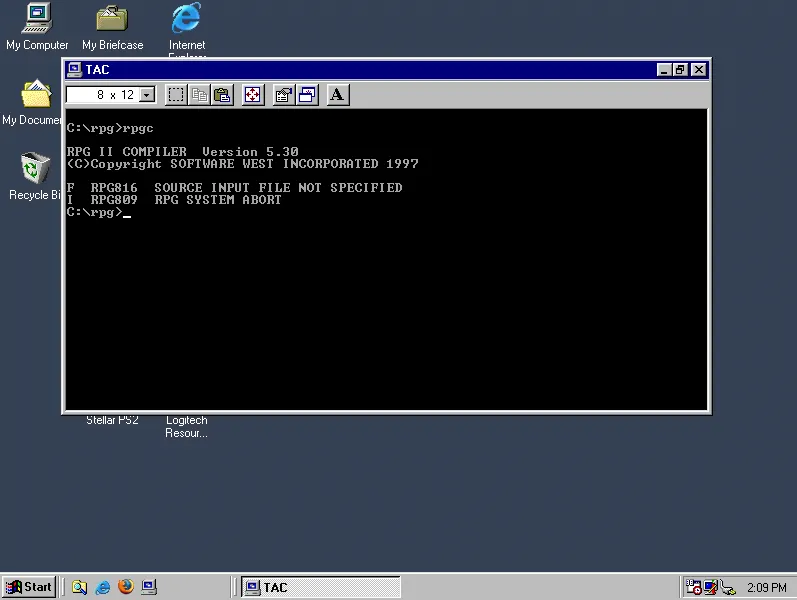

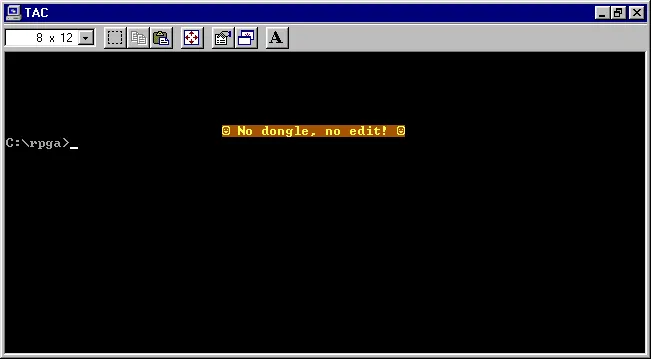

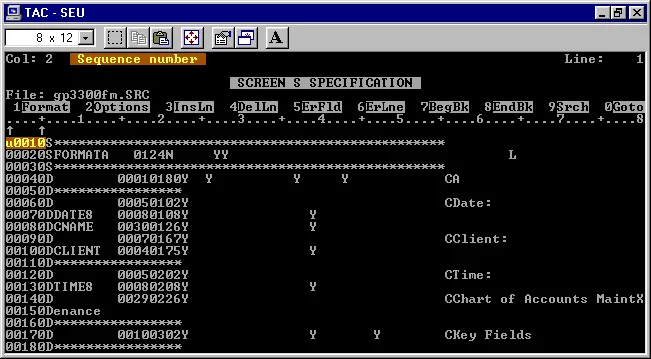

The compiler consists of several executable files, in particular, RPGC.EXE (the compiler) and SEU.EXE (the source editor, Source Entry Utility). Here’s what we get a few seconds after launching SEU without the dongle:

A bit rough, but this gives us an important clue: this program tries to exchange data through the parallel port for a few seconds (which might allow us to pause it for debugging and see what is happening at that time), and then exits with a message (which we can now find in the disassembled code of the program and trace how it gets to this point).

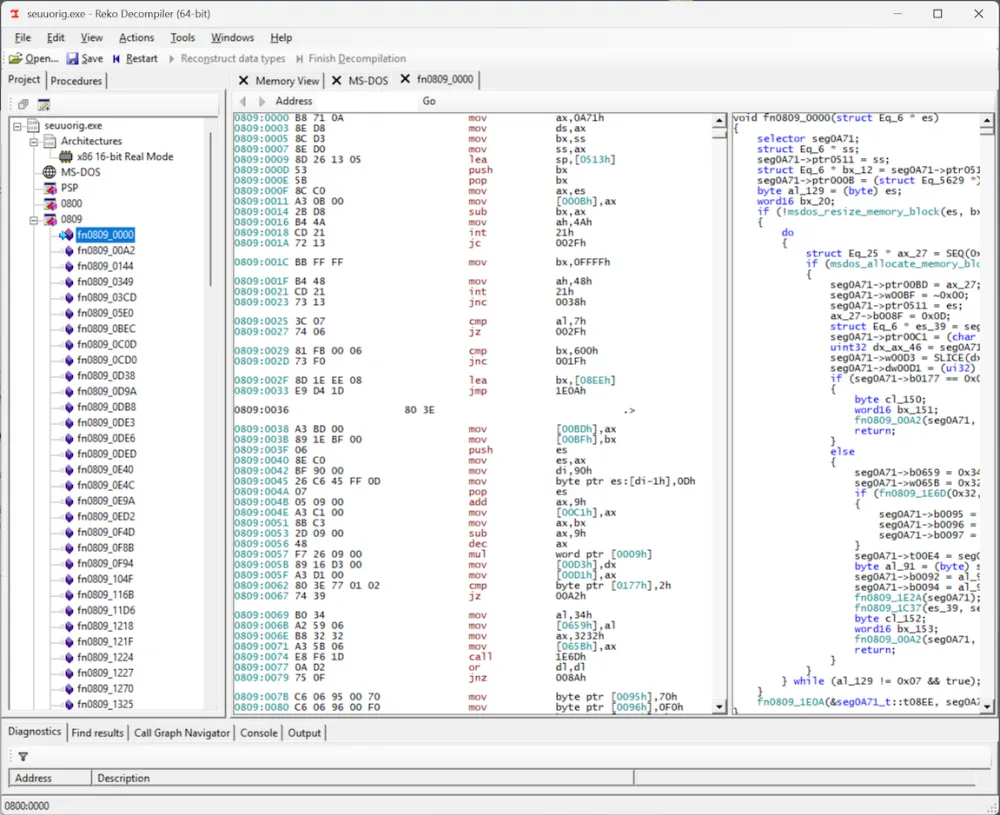

An excellent tool for disassembling such vintage executables is Reko. It understands 16-bit real mode executables and even attempts to decompile them into readable C code corresponding to the disassembled code.

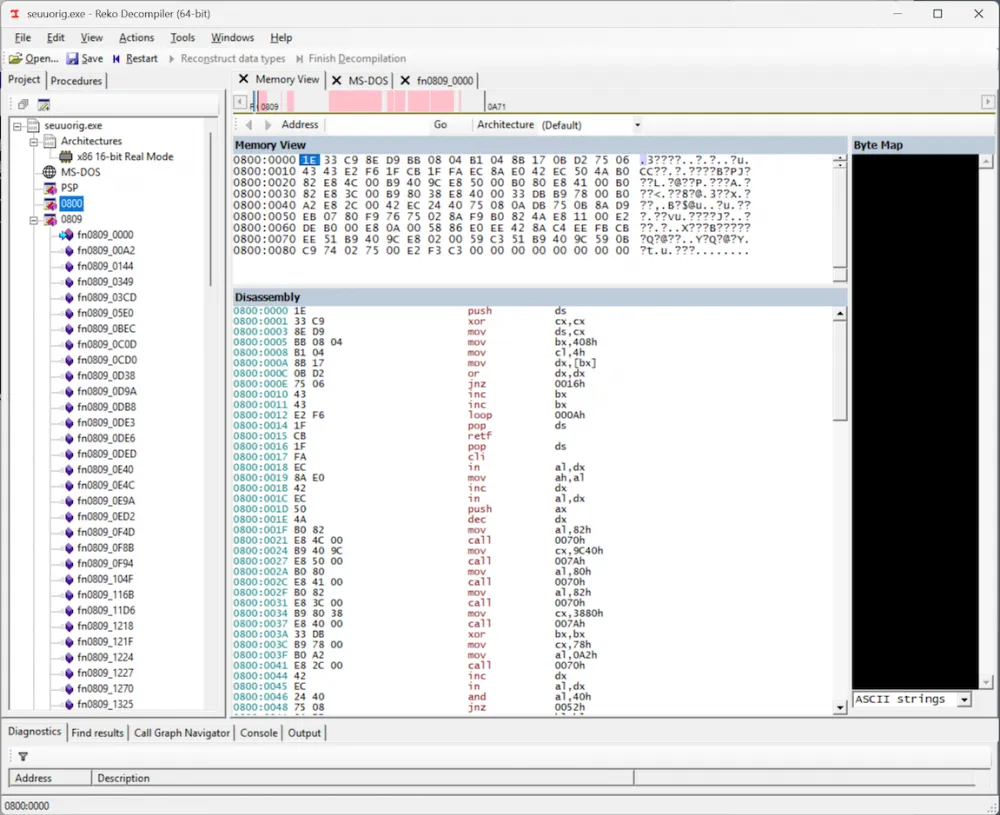

While studying the decompiled/disassembled code in Reko, I expected to find the in and out commands, which would indicate that the program is trying to communicate with the parallel port through the PC's input-output ports. However… I couldn't find these commands anywhere! But then I noticed something: Reko disassembled the executable file into two "segments": 0800 and 0809, and I was only examining the 0809 segment.

Upon examining the 0800 segment, we find a clue: the in and out commands, indicating that the write protection subroutine is definitely located here; moreover, the entire code segment is only 0x90 bytes in size, which means the subroutine will be fairly easy to disassemble and understand. For some reason, Reko was unable to decompile this code into C code but still created disassembled code that we will find sufficient. Perhaps it was a primitive form of obfuscation from that era that confused Reko and prevented it from associating this block of code with the rest of the program... who knows.

The disassembled code along with my annotations and notes can be found at GitHub Gist. I've already forgotten some x86 assembly, but I will briefly describe what this code does:

This is definitely a single autonomous subroutine designed to be called using the "far" command

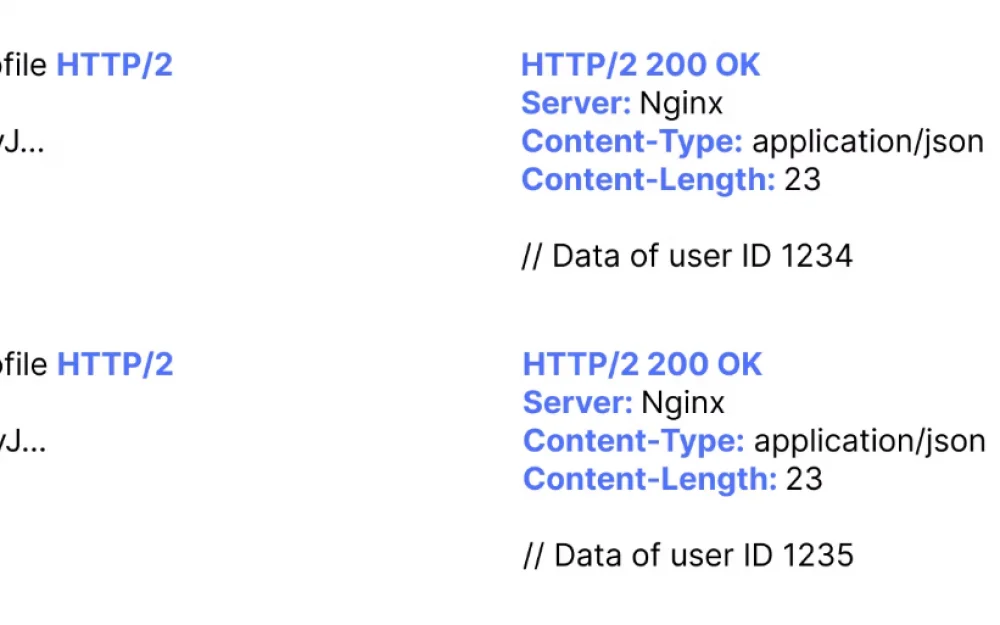

CALL, because it performs a return with the commandRETF.First, it determines the address of the parallel port by reading the BIOS data area. If the computer has multiple parallel ports, the dongle must be connected to the first (LPT1).

The subroutine executes a loop in which it writes values to the data register of the parallel port, then reads the status register and accumulates responses in the registers

BHandBL.By the end of the subroutine, the "result" of the entire procedure is saved in the register

BX(BHandBLtogether), which will presumably be "checked" by the calling side.It is very important that there seems to be no "input" performed in this subroutine. It does not extract anything from the stack and does not care what values are passed to its registers. This can only mean that the result of this subroutine is completely constant! No matter how complex the data exchange it performs with the dongle, the result must always remain the same.

Knowing that this subroutine should exit with some magical value saved in BX, we can patch the first few bytes of the subroutine to do just that! Not knowing yet what value should be placed in BX, let's start with 1234:

BB 34 12 MOV BX, 1234h

CB RETFWe need to patch only the first four bytes — assign BX the value we need and perform the exit (RETF). If we run the patched executable file with these new bytes, it will still terminate with the same message (as expected), but the execution stops immediately, rather than after several seconds of communication with the parallel port. Progress!

Step by step, examining the disassembled code, we get another important clue: the only value that BH can have at the end of the subroutine is 76h (it is hardcoded in the subroutine). Thus, the total value of the magical number in BX must take the form 76xx. In other words, the only unknown remains the value of BL:

BB __ 76 MOV BX, 76__h

CB RETFSince BL is an 8-bit register, we have only 256 possible values. So what do we do if we need to check just 256 combinations? We brute-force them! I wrote a script that substitutes a value into this specific byte (from 0 to 255), programmatically launches the executable file in DosBox, and observes the output. It worked! The brute-force didn't take much time because the needed number turned out to be… 6. This means the final magic number in BX should be equal to 7606h:

BB 06 76 MOV BX, 7606h

CB RETFBingo!

After examining other executables in the compiler package, it turned out that the parallel port subroutine is identical. All executable files share the same logic for copy protection. When the compiler (RPGC.EXE) compiles RPG source code, it seems to copy the parallel port subroutine from itself into the compiled program. And yes, the patched version of the compiler will generate the same patched copy protection subroutine! Very convenient.

I must say, this copy protection mechanism seems a bit... simplistic. A hardware dongle that just returns a constant number? And protection that can be bypassed with a four-byte patch? Is it really worth a patent? But who am I to judge? Perhaps I haven't fully grasped the logic, and the copy protection will resurface in some other way. It's also possible that the creators of the RPG compiler (Software West, Inc) did not fully leverage the hardware dongle and used it in an easily bypassable manner.

In any case, the RPG II compiler from Software West is now free from the parallel port dongle binding! Soon I plan to remove all personal information from the compiler folders so I can release this compiler as an artifact of computer history. It seems it's nowhere else on the web. If any of the readers are associated with Software West Inc, please contact me; I have many questions!

Write comment