- AI

- A

Forbidden Fruit Has Been Picked

Astrophysicist David Kipping attended a closed meeting at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study. He returned shaken and recorded an hour-long podcast. I listened to it all so you wouldn't have to.

In January, David Kipping came to Princeton to give a colloquium on astronomy. In the hallway of the Institute for Advanced Study, he crossed paths with Ed Witten — one of the fathers of string theory. Just crossed paths, as people often do in hallways. Einstein, Oppenheimer, Gödel walked the same corridor. This is not a place where nonsense is usually tolerated.

Kipping is a professor at Columbia University, the author of the YouTube channel Cool Worlds (one and a half million subscribers), with ten years in ML/AI. Eight years ago, he stopped developing models himself: he couldn’t keep up with the literature and decided that you’re either full-time in AI or you use all this as a tool. He chose the latter. Publications on predicting the stability of circumbinary planets, discovering “missed” exoplanets. An active scientist with a research portfolio, not a journalist or a casual blogger.

The next day, he habitually stopped by the IAS and ended up at a closed meeting. It was organized by one of the senior astrophysics professors (Kipping intentionally does not name him). Topic: the impact of AI on science. Forty minutes of presentation, then a historian’s comment via Zoom, followed by discussion. There were about thirty people in the room, including the authors of the cosmological simulations Enzo, Illustris, Gadget. Hydrodynamics with adaptive meshes, hundreds of thousands of lines of C and Fortran. Try, as Kipping put it, to find a room with a higher average IQ.

The meeting was internal: no cameras, no press releases, no prepared statements. Not a conference, not a promotional event. That’s why people said what they really thought.

The historian spoke first: this is a historic moment, it needs to be documented.

The room laughed. Kipping did not.

Capitulation

The host's first assertion: AI codes an order of magnitude better than humans. That’s right — complete dominance, the quality of the code is an order of magnitude higher. Not a single person in the room raised their hand to object. Not one.

Then came the numbers. The leading professor said that AI is capable of performing about ninety percent of his intellectual work. He added: maybe sixty, maybe ninety-nine. But he made it clear that more than half, and the share would be growing. It wasn't just about coding. Analytical thinking, mathematics, problem-solving. All that a person in IAS dedicated his life to.

A specific example from Kipping. He was working on integrating functions in Mathematica, the main tool for symbolic computation, a product of Stephen Wolfram. Mathematica couldn't handle it. ChatGPT 5.2 did. It showed the full chain of substitutions and transformations, which Mathematica doesn’t do at all. The result was checked numerically. It matched.

When a person from IAS (let me remind you — Gödel worked here) admits that the model performs ninety percent of his cognitive work, no marketer could come up with a more terrifying formulation. An identity crisis, voiced out loud, in front of witnesses. The witnesses nodded and rejoiced.

The key to the apartment where the money lies

The leading professor handed over full control of his digital life to agent systems. Email, files, servers, calendars. Root access in Unix terms. The main tools are Claude and Cursor, with GPT on standby. About a third of the audience raised their hands: us too.

Someone asked about privacy: have you even read the user agreement?

Answer: “I don’t care. The advantage is so great that losing privacy is irrelevant.”

Next came ethics. Standard concerns were listed: jobs, energy consumption, climate, the power of billionaires. The leader acknowledged them. And literally said: I don’t care, the advantage is too great. Kipping describes the mood of the hall as “to hell with ethics.” This was not an isolated opinion of a radical oddball. The audience agreed.

Here it is worth stopping and thinking about what exactly we are observing. Academics are masters of diplomatic caveats. Their entire career is the skill of saying "there are nuances" instead of "yes" or "no." And these very people, in a closed circle, without cameras, say "I don't care about ethics." The very position is predictable (if your job is to maximize scientific results, you optimize your work for results). But the willingness to say this out loud, without reservations—that shows the level of pressure they feel. Previously, even in the smoking room, they were embarrassed to formulate it this way.

The metaphor that Kipping used to describe the situation: "forbidden fruit." AI companies are the serpent offering the apple. Once bitten, innocence cannot be returned. And if you don't take a bite, but a competing lab does—they will overtake you. An arms race with a moral dilemma inside.

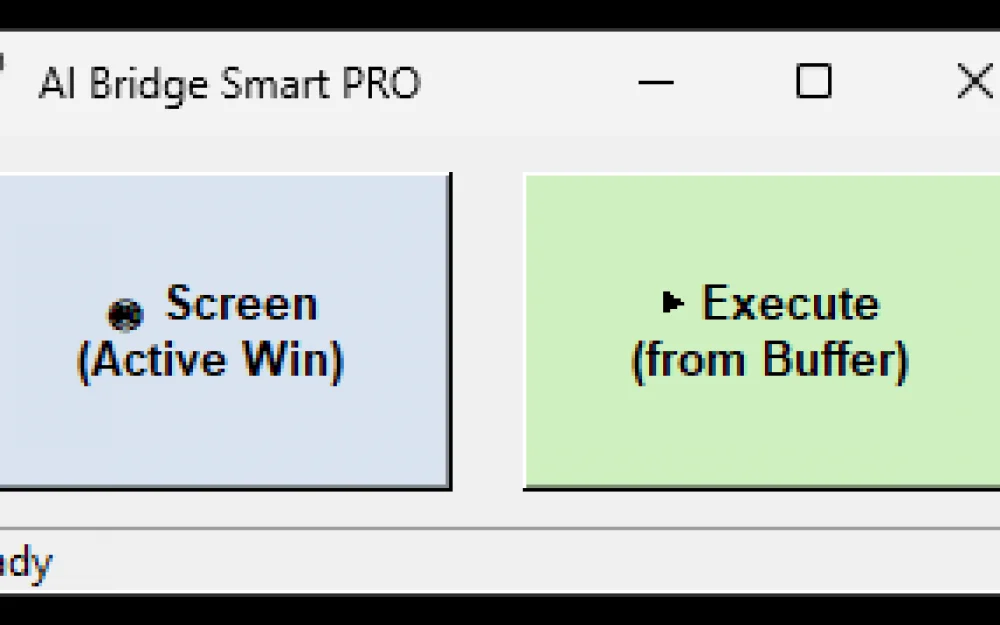

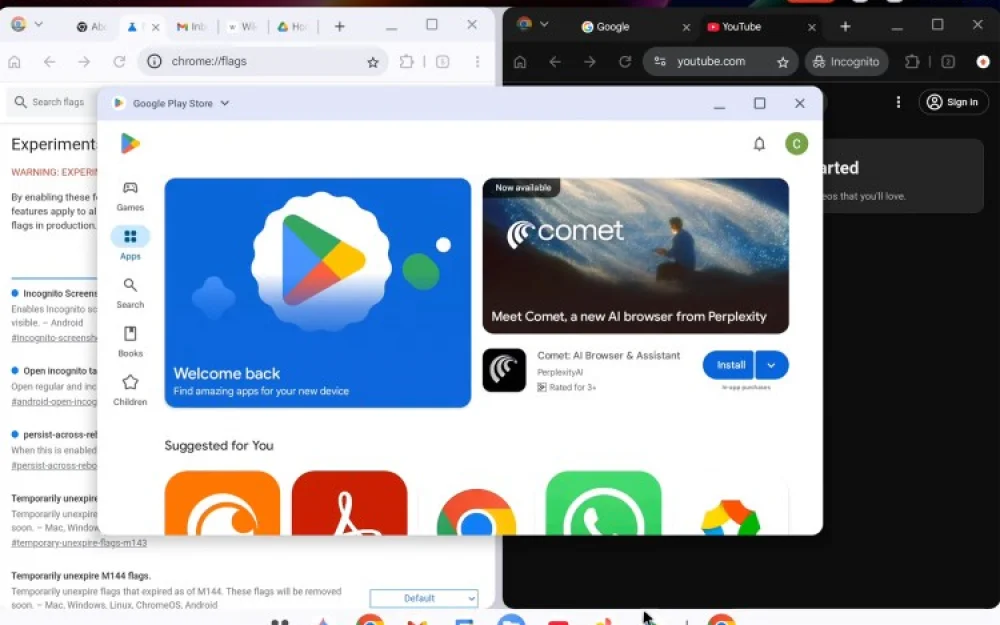

Interestingly, this feeling of inevitability is not abstract; it is confirmed by experience. Kipping describes his own workflow: proofreading articles (LaTeX directly in GPT), vibe coding (although he still writes most of the code himself), debugging (he almost never debugs manually, he copies the error into chat), literature search, calculating derivatives for articles, and even interdisciplinary work: when the TARS project needed to understand the properties of graphene, albedo, and mechanical strength, he ran everything through AI. For YouTube: DXRevive for audio cleaning, lalalai.ai for separating music, Rev.com for transcripts, Topaz for upscaling, GPT for fact-checking scripts.

At the same time, Kipping does not consider himself a superuser. His self-assessment: "My strength has always been in creativity—AI enhances it." A leading professor, according to Kipping, has gone much further. There is a chasm between "I use it for proofreading" and "I gave root access to the servers," and in this chasm live all the stages of acceptance that scientists go through over a year or two.

Shameless plug. Check out my channel about neural networks:

"Revelations from Oleg" (https://t.me/tg_1red2black)

How Trust Grows

This may be interesting for those working on alignment, interpretability, or simply setting up agent pipelines in production.

The lead professor described his trajectory. He started with Cursor — because Cursor shows the diff. Here’s what was, here’s what became, here’s what I changed in your code. Transparent, verifiable, familiar to the programmer. But as trust grew, transparency began to irritate. It no longer felt like security and started to feel like friction. The professor switched to Claude. Claude sends sub-agents, decomposes the task, solves it in pieces, acts more autonomously. It doesn’t show every diff. It just does.

The professor organized verification between the models: he solved the task in Cursor, double-checked in Claude, discussed the result in GPT. Essentially peer review. Just not among colleagues, but between three neural networks.

If you formalize this trajectory, you get an S-curve: skepticism, disappointment, time investment, surprise, trust, transfer of control. In the last phase, transparency turns into an interference — like the buzzing of a fly when you are trying to concentrate. The leading scientists of the world stand on the upper plateau of this curve.

Here’s what this means for everyone building interpretable and explainable systems: high-level users do not need your transparency. They will turn it off. Not because they were forced, not because the interface is bad — but because it’s more convenient for them without it. Natural selection within user behavior pushes towards less interpretable systems. For the alignment community, this should be a warning sign: the better models work, the less incentive users have to monitor them.

Side effect: small scientific collaborations will begin to disappear. Previously, a scientist would attract a co-author because they lacked a skill — calculation, verification, code in an unfamiliar library. Now this gap is filled by the model. Why call a colleague for a single calculation if Claude can do it in ten minutes? Kipping writes scientific papers alone, which is unusual for his field, and suggests that the trend will strengthen. Core collaborations will remain — two to three people, where each is irreplaceable. The rest will be taken over by agents.

The first contact with models usually disappoints. The lead professor admitted that he spent a huge amount of time on trial and error. He screamed at the keyboard in all capital letters for hours. People try once, get junk, and give up. Those who went through this — the early adopters — gain a colossal advantage. Hence the motivation for the meeting: the institute did not resist but formed a group for accelerated implementation. The message was clear: take this to work, relax, and enjoy.

The Economics of the Trap

The lead professor spent hundreds of dollars a month on subscriptions. From personal funds. For him, this is bearable. For a graduate student or a young postdoc, it is already a barrier. Stratification is happening right now: some are enhanced by AI, while others cannot afford the enhancer.

The scale of investment in the AI industry since 2014 exceeds the entire Apollo project by more than five times (adjusted for inflation) and the Manhattan Project by fifty times. Humanity has not invested such sums in any technology.

The question that arose at lunch: how will investors recover these amounts? One scenario is a price trap. A classic dealer scheme: the first dose is free. Models are cheap right now. Everyone gets used to it. Skills atrophy. In a couple of years, companies will raise the price to thousands of dollars a month. By that time, the Overton window will have shifted: the level of productivity with AI has become the expected norm, and it will be impossible to refuse — like GPS, the habit is there, and the skills to live without a navigator have long since faded.

The second scenario was discussed at lunch with particular fervor: AI companies may demand a share of intellectual property. Imagine service conditions where OpenAI or Anthropic take ten-twenty-fifty percent of patents for using a "research" rate. So far, this is speculation. But two hundred billion dollars in investments require a return, and charity won't cut it.

This topic is hardly discussed publicly. And that's a pity: if your grant pays for work, and twenty percent of IP goes to Anthropic — that’s a different economy of research.

Who Suffers the Most

Traditionally, in physics and astrophysics, technically skilled individuals have prevailed. The ability to solve differential equations in one's head, to write complex simulations, to think abstractly. These advantages have been neutralized by the emergence of AI.

The new profile of the "super-scientist" is managerial. The ability to break a problem into pieces suitable for modeling. Patience—not to lose it when the model confidently returns nonsensical results for the third time. The skill of building a workflow: prompts, rules, chains of agents. A completely different breed of people compared to those who have advanced science over the last three hundred years. As if a conductor were told: the orchestra is now virtual, you can throw away the baton, learn to write MIDI.

The analogy with GPS is accurate and harsh. Before navigators, we kept a three-dimensional map of the terrain in our heads. GPS has killed that skill. While driving, we now think about anything but the route. Atrophy of coding skills, mathematical thinking, independent problem-solving: the same thing, only on a larger scale.

The most vulnerable group: young scientists. Training a PhD student costs around one hundred thousand dollars a year—salary, health insurance, tuition. A subscription to the model: twenty dollars a month. The first-year project that a student spends twelve months on can be consumed by the model in an evening.

Against this backdrop, there is a cut in federal grants by the current administration. And the existential question that Kipping clearly marks as "I am not for this, but I can imagine that someone would say": why spend five years training a scientist if, in five years, scientists in the traditional sense may no longer exist?

Tenured professors are relatively safe—by definition of tenure, to fire them, one would need to eliminate the entire institution. Captains who will sink along with the ship. Part of the ship, part of the crew.

A leading professor is already using AI for selecting graduate students—not for making decisions, but for assisting. The outcome of this implementation is assessed as the best in all practice: faster, more accurate, more reliable.

Question that sends shivers down the spine: what criteria to use for selecting students, if traditional ones (technical skills, coding ability, abstract mathematics) might become meaningless in five years? Kipping puts it bluntly: would he agree to work with a student who fundamentally refuses to use AI? Most likely not. It’s like fundamentally refusing to use the internet or refusing to write code.

What is left unsaid at conferences

There are things that were not mentioned at the meeting, but their shadow falls on every fact from the podcast.

If models write ninety percent of the work and cross-check each other, who will notice a systematic error common to all? When everyone uses the same systems, the diversity of viewpoints narrows. Let's say three models agree that the integral is taken this way. But what if all three inherited the same approximation from the training data? An individual reviewer with a pencil could catch it — but reviewers are overwhelmed with papers, they have no time, and they too are increasingly checking through the model.

Reproducibility is already a painful topic in science (google replication crisis if you’re unaware: half of results in psychology are not reproducible, and the situation in biomedicine is not much better). Now add to this: the experiment "ran a prompt, got a result." How to reproduce it a year later when the model has been updated? What was the sampling temperature? What was the default system prompt on that Tuesday? Which version of the model was used? Reproducibility either gets a second wind or a fatal blow. It depends on whether we learn to document the prompt environment as strictly as we document library versions in requirements.txt.

If models generate science, and science feeds into the data for training the next generation of models, this is a closed loop. Whether it converges to something meaningful or diverges, we do not know. Model collapse as a concept is widely discussed, but in the specific context of scientific knowledge, it is almost nowhere to be found. Scientific texts are structured differently than copywriting: there are chains of reasoning where an error in the middle breaks the entire logic. If a model trains on ten thousand articles where an intermediate step is a product of hallucinations, but the final result coincidentally matches reality, it will learn bad reasoning along with correct answers. This is even worse than an outright mistake.

Another topic that Kipping touches on, but in a different context, is public reaction. The YouTube audience has a strong allergy to anything that smells like "AI slop" — content that is entirely generated by a model, regurgitated Wikipedia, rewritten Reddit. Kipping draws a line: his content is based on unique ideas, the model helps with execution and formatting, not with ideas. But what is telling is that the scientists at IAS were not at all concerned about the public's reaction. They are not afraid that an article will be labeled as generated because they have long acknowledged: models work at their level or above. From their perspective, AI-assisted science is absolutely legitimate. The gap between academic perception and public perception is already a chasm, and the chasm will grow.

A paper storm. There appears to be one or two orders of magnitude more publications. Supermen write three to four articles a year instead of one, and "ordinary people with GPT" have also gained the ability to write their own. Even now, dozens of works in every field of knowledge are posted daily on arXiv. There is no one to read them. "Use AI for reading" is the obvious answer, but a scholar needs to internalize knowledge, not just get a summary. To cram it into their head, digest it, connect it with what they already know. Summaries do not provide that.

The Last Question

What is the point of replacing all scientists with machines?

Kipping draws an analogy with art. AI art exists, and it is useful for certain tasks. But in a museum, we are captivated by the human story: what drove the artist, what was happening around them, why exactly that brushstroke in that place. Science is the same nature of curiosity. A detective's work. The joy when pieces come together and you suddenly understand how a fragment of the world is arranged.

Kipping is afraid of very specific things. A world where a superintelligence designs a thermonuclear reactor, and people are unable to understand how it works. A world where the result exists, but understanding does not. Where everything around is magic. He says: “I don’t know if I want to live in a world where everything is just magic, fantasy. I want to live in a comprehensible world.”

If we plug in the numbers: the model costs twenty dollars and does the work of a PhD student. This means science ceases to be a privilege of the elite. The viewers of Kipping’s channel, who have been writing to him with ideas for years, no longer need Kipping to realize them. “Democratization.” Sounds wonderful. But the consequence is an avalanche of publications, where human attention becomes the main scarcity. Values shift: not “who can do science,” but “who can separate the grain from the chaff.” A completely different skill. And perhaps the last one that humans will have to learn to use.

Kasparov lost to Deep Blue in ’97. Then for ten years he promoted the idea of “centaur chess”: man plus machine is stronger than the machine alone. By 2015, it became clear that no—the machine alone is stronger. The centaurs quietly left the stage without any honors. In science, we are now somewhere in the centaur phase: humans are still needed, humans still manage the process, humans still formulate questions. How long this will last is not an abstract question. For some of those graduate students currently being selected, the answer will come before their dissertation defense.

The most striking thing about this podcast is not the content. Anyone who works daily with LLM will recognize their own thoughts in it. What is astonishing is something else. Kipping says: what shocked him was not what he heard, but that all of it was spoken aloud, and the whole room nodded. Thoughts he considered his personal worries, uncertain, half-formed, frightening, turned out to be a common chorus. Until that January morning, no one had dared to say so.

The historian who spoke there via Zoom was right: this moment needs to be documented. Kipping documented it. I recorded it in text. Habr residents read it.

But who will read it in five years—us, or the systems to which we will delegate reading by then—no one in that room answered this question.

However, perhaps it wasn’t necessary. It is enough that the question was asked.

Based on materials from the Cool Worlds podcast (David Kipping, Columbia University), an episode about a closed meeting at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, 2025.

Write comment