- AI

- A

Teenage Period of Technology

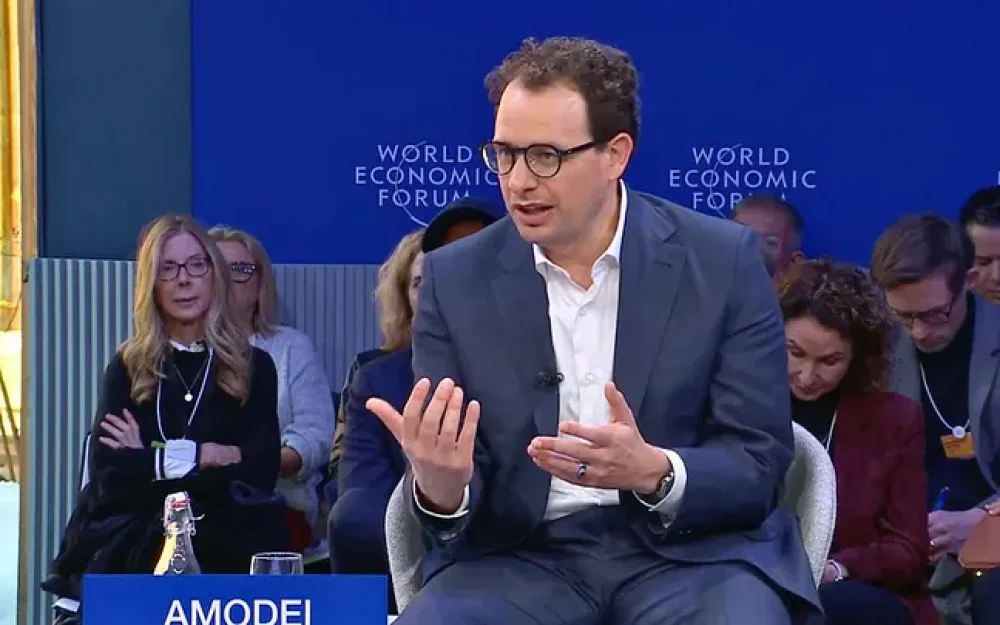

This is a translation of Dario Amodei's essay "The Teenage Period of Technology." Yes, we are already terribly tired of articles about AI. And here is a long read! But I still decided to translate this essay. The author is the CEO and co-founder of Anthropic. In 2025, he was listed among Time's 100 most influential people, previously worked at OpenAI, overseeing the creation of GPT-2 and GPT-3. He was named one of the "architects of artificial intelligence," whom Time selected as "Person of the Year," alongside the guys and girls in the picture.

Amodei talks about various risks and safety aspects in a world where AI is becoming increasingly powerful. Some of his ideas are extremely "hawkish," so while translating the text, I had to soften (while preserving the meaning) some of his rather sharp attacks against countries he considers "enemies of democracies." Nevertheless, it’s possible that Amodei is now anticipating some political trends and points of tension both between different countries and within countries, including Western democracies, and these points of tension are created by the rising power of AI...

Dario Amodei

The Adolescence of Technology

Confronting and Overcoming the Risks of Powerful AI

January 2026

The Adolescence of Technology

Confronting and Overcoming the Risks of Powerful AI

January 2026

In the film adaptation of Carl Sagan's book "Contact," there is a scene where the main character, an astronomer who discovered the first radio signal from an alien civilization, is considered a candidate to represent humanity in a meeting with aliens. The international commission conducting the interview asks her: “If you could ask them only one question, what would that question be?” She replies: “I would ask them: ‘How did you do it? How did you go through the evolution process and survive the adolescence of technology without destroying yourselves?’”

When I think about where humanity stands now in terms of AI, and what we are on the brink of, my thoughts constantly return to this scene. Because this question reflects our current situation so accurately. And I wish we had an answer from aliens that could help us find the right path.

I believe that we are entering a kind of tumultuous but inevitable rite of passage that will test who we are as a species. Humanity is about to be handed an almost unimaginable power, and it is utterly unclear whether our social, political, and technological systems are mature enough to manage it.

In my essay "Machines of Loving Grace" (Machines of Loving Grace), I attempted to describe the dream of a civilization that has reached maturity, where risks are eliminated, and powerful AI is applied skillfully and compassionately, enhancing the quality of life for all. I suggested that AI could contribute to breakthrough achievements in biology, neuroscience, economic development, the global community, as well as in the labor sphere and even in the quest for the meaning of life. I felt it was important to give people something inspiring to fight for. This is a task that, strangely enough, both proponents of accelerated AI development ("accelerationists") and advocates of AI safety have failed to achieve.

But in this essay, I want to address the rite of passage itself: to outline the risks we will face and begin to develop a battle plan for overcoming them. I deeply believe in our ability to succeed, in the spirit and nobility of humanity, but we must face the reality of the situation with clear eyes and without illusions.

As with the discussion of benefits, I find it extremely important to talk about risks carefully and thoughtfully. In particular, I believe the following points are important:

Avoid "doomism". By "doomism," I mean not only the conviction in the inevitability of doom (which is false in itself and becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy), but also a broader perception of AI risks in a quasi-religious context(1).

(1) This is symmetrical to what I expressed in “Machines of Loving Grace,” where I started by stating that we should not perceive the benefits of AI as a prophecy of salvation, and that it is important to be specific, grounded, and avoid grandiosity. Ultimately, both prophecies of salvation and prophecies of doom hinder a sober look at the real world—for essentially the same reasons.

Many people have been analytically and soberly reflecting on AI risks for many years, but in my impression, at the peak of fears regarding AI in 2023-2024, the most unreasonable voices came to the forefront, often amplified through social media. These voices used repulsive language reminiscent of extreme religiosity or science fiction, calling for drastic measures without sufficient evidence to justify such steps. It was already clear then that a backlash was inevitable, and the issue would become culturally polarized, thus—blocked(2).

(2) Anthropic's goal is to maintain consistency despite such changes. When the discussion of AI risks was politically trendy, Anthropic cautiously advocated for a balanced and evidence-based approach to these risks. Now that talking about AI risks has become politically unpopular, Anthropic still cautiously supports a balanced and evidence-based approach to these risks.As of 2025-2026, the pendulum has swung the other way: today, political decisions are increasingly dictated by the opportunities of AI rather than its risks.

This inconsistency is unfortunate, as the technology itself doesn't care what's currently in vogue, and by 2026 we have become significantly closer to real danger than we were in 2023.

The lesson here is this: we must discuss and address risks realistically and pragmatically, soberly relying on facts and being prepared for changes in public sentiment.

Recognize uncertainty. There are many scenarios in which the concerns outlined here may turn out to be irrelevant. Nothing in this essay should be taken as a statement about the truth or even the likelihood of threats. First of all, AI may simply not develop as quickly as I assume(3).

(3) Over time, I have increasingly been convinced of the trajectory of AI development and the likelihood that it will surpass human abilities in all areas, but some uncertainty remains.Even if it develops rapidly, some or all of the risks described here may never materialize (which would be wonderful), or other, unaccounted-for threats may arise. No one can predict the future with complete certainty, but we must do everything we can to plan ahead.

Intervene as precisely as possible. Addressing the risks associated with AI will require a combination of voluntary actions by companies (and private independent actors) and mandatory measures enacted by governments.

Voluntary actions, their implementation, and encouraging other companies to follow suit seem to me an obvious necessity. I firmly believe that government intervention will also be needed, although such measures are fundamentally different: they can destroy economic value or coerce dissenting participants who are skeptical about these risks (and perhaps they will be right!). Furthermore, regulation often has a counterproductive effect or exacerbates the problem it is supposed to solve (especially in the case of rapidly changing technologies).

Therefore, it is crucial that regulation be prudent: it should strive to avoid collateral damage, be as simple as possible, and impose the minimum necessary burden to achieve its objectives(4).

(4) Export control regarding chips is a great example of such an approach. It is straightforward and, it seems, mainly works effectively.It's easy to say: “No measures are excessive when it comes to the fate of humanity!,” but in practice, such an approach only provokes backlash.

Of course, it is quite possible that over time we will indeed reach a point where much more decisive measures are required, but this will depend on the emergence of more compelling evidence of impending and specific danger than what we have today, as well as sufficient specificity of the threat itself to formulate rules that can realistically eliminate it.

The most constructive thing we can do today is to advocate for limited, targeted rules while we gather data supporting (or refuting) the necessity of stricter measures(5).

(5) And, of course, seeking such evidence should be intellectually honest, meaning it may also reveal a lack of danger. Transparency through system maps of models and other forms of disclosure is an attempt at exactly such intellectually honest activity.

Taking all of the above into account, the best starting point for discussing the risks of AI, it seems to me, is the same question I began my reflections on its advantages with: it is necessary to clearly define what level of AI we are talking about.

The level of AI that raises civilizational concerns for me is that very " powerful AI " that I wrote about in "Machines of Loving Grace". I will simply repeat here the definition given in that essay:

By "powerful AI," I mean an AI model (likely resembling modern large language models, LLMs, although it may be based on a different architecture, include multiple interacting models, and use different training methods) that possesses the following properties:

In terms of pure intelligence, it is smarter than a Nobel Laureate in almost all relevant fields: biology, programming, mathematics, engineering, writing, etc. This means it is capable of proving unresolved mathematical theorems, writing exceptionally good novels, creating complex codebases from scratch, and so on.

In addition to being simply a "smart conversationalist," it has all the interfaces available to a person working remotely: text, audio, video, mouse and keyboard control, internet access. It can perform any actions, communications, or remote operations possible through these interfaces: acting on the internet, giving or receiving instructions from people, ordering materials, conducting experiments, watching and creating videos, etc.—and it does all of this with a level of mastery that surpasses the best humans in the world.

It does not just passively answer questions; tasks can be assigned to it that take hours, days, or weeks to complete, and then it independently takes on the problem-solving as a smart employee would, asking for clarifications when necessary.

It does not have a physical body (except for its presence on a computer screen), but it can control existing physical tools, robots, or laboratory equipment via a computer; in theory, it could even design robots or equipment for its own use.

The resources used for its training can be redirected to launch millions of copies of it (this corresponds to the predicted sizes of computing clusters by ~2027), and each copy can perceive information and generate actions roughly 10–100 times faster than a human. However, its speed may be limited by the constraints of the physical world or the software it interacts with.

Each of these millions of copies can work independently on different tasks or, if necessary, collaborate, as people do, possibly with different subgroups of models further trained on specific tasks.

This can be summarized as "a country of geniuses in a data center".

As I wrote in “Machines of Loving Grace,” powerful AI could emerge in just 1–2 years, although it may also appear significantly later (6).

(6) Indeed, since the writing of “Machines of Loving Grace” in 2024, AI systems have become capable of performing tasks that take humans several hours: a recent METR assessment showed that Opus 4.5 can accomplish an amount of work equivalent to four human hours with 50% reliability.

The exact moment of its emergence is a complex topic worthy of a separate essay, but for now, I will briefly explain why I believe it could happen very soon.

My co-founders at Anthropic and I were among the first to document and begin tracking the “laws of scaling” of AI systems — the observation that as computational resources and training data volumes increase, AI systems predictably improve across nearly all measurable cognitive skills. Every few months, public opinion oscillates between believing that AI has “hit a wall” and being inspired by a new breakthrough that “will change the game,” but behind all this volatility and public speculation lies a smooth and steady growth in AI’s cognitive capabilities.

We have now reached a point where AI models are beginning to make strides in solving unsolved mathematical problems and are programming so well that some of the best engineers I have ever met are now handing over almost all their coding to AI. Just three years ago, AI struggled with elementary arithmetic problems and could barely write a single line of code.

Similar rates of improvement are observed in biology, finance, physics, and many tasks requiring autonomy (agentic tasks). If this exponential trend continues (although this is not guaranteed, it is already supported by a decade of statistics), then it will not be long before AI surpasses humans in literally everything.

In fact, this picture likely even underestimates the expected rates of progress. As AI is already writing a significant portion of the code at Anthropic, it substantially accelerates our own pace of developing the next generation of AI systems. This feedback loop is gaining momentum month by month and may reach a point in just 1–2 years where the current generation of AI can autonomously create the next. This cycle has already begun and will rapidly accelerate in the coming months and years. Observing the progress of the last five years from within Anthropic and looking at how the models for the next few months are being shaped, I feel this accelerating pace and countdown.

In this essay, I will assume that this intuition is at least partially correct. Not in the sense that powerful AI will necessarily emerge in 1–2 years(7), but that there is some probability of this happening, and a very high probability of its emergence in the next few years.

(7) And to be clear: even if powerful AI appears in a technical sense in 1–2 years, many of its social consequences, both positive and negative, may not become apparent until several years later. That is why I can simultaneously believe that AI will displace 50% of simple white-collar jobs within 1–5 years, while also believing that AI surpassing all humans in capabilities could appear in just 1–2 years.

As in “Machines of Loving Grace,” a serious consideration of this assumption can lead to surprising and concerning conclusions. There, I focused on the positive consequences, while here — on those that cause worry. These are conclusions we may not want to confront, but that does not make them any less real. I can only say that day and night I think about how to steer us toward positive outcomes and away from negative ones, and in this essay, I will detail how to achieve that.

I think the best way to recognize the risks associated with AI is to ask the following question: imagine that in ~2027, somewhere in the world, a literal “country of geniuses” suddenly emerges. Suppose 50 million people, each of whom is far more capable than any Nobel laureate, statesman, or technologist. The analogy is imperfect, as these “geniuses” may have an extraordinarily wide range of motivations and behaviors — from fully obedient and submissive to strange and “alien” in their impulses. But for now, let’s put aside the analogy and imagine that you are a national security advisor for a major state, responsible for assessing and responding to this situation. Also imagine that since AI systems can operate hundreds of times faster than humans, this “country” has a temporal advantage over all other countries: for every cognitive action on our part, this country can perform ten.

What should concern us?

I would be worried about the following:

Risks of autonomy. What are the intentions and goals of this country? Is it hostile or does it share our values? Can it achieve military dominance over the world through superior weapons, cyber operations, influence operations, or production?

Malicious use for destruction. Suppose the new country is pliable and "follows instructions," meaning it essentially acts as a mercenary state. Can existing malicious actors who wish to cause destruction (e.g., terrorists) exploit or manipulate some of these people to significantly amplify the scale of destruction?

Malicious use for power grab. What if this country was actually created and controlled by an already powerful entity—a dictator or a malicious corporation? Can this entity use it to achieve dominating influence over the entire world, disrupting the existing balance of power?

Economic upheavals. Even if the new country does not present a security threat in any of the ways mentioned above and simply participates peacefully in the global economy, can it still create serious risks just due to its technological superiority and efficiency, causing global economic upheavals, mass unemployment, or radical concentration of wealth?

Unintended consequences. The world will change very rapidly due to all the new technologies and productivity created by the new country. Could some of these changes turn out to be radically destabilizing?

I think it should be clear that this is a dangerous situation. A report from a competent national security advisor to the head of state would likely contain words like: “the most serious national security threat in a century, possibly in all of history.” It seems that this is where the efforts of the best minds of civilization should be directed.

At the same time, it would be absurd to shrug and say, "There's nothing to worry about!" However, faced with the rapid progress of AI, that seems to be the position many American politicians take, some of whom deny the very existence of AI risks, focusing only on familiar, clichéd political issues(8).

(8) It is worth adding that the public (unlike politicians) is indeed very concerned about the risks of AI. Some of their concerns, in my opinion, are justified (for example, job displacement), while others are misguided (for instance, worries about water consumption by data centers, which is actually negligible). This reaction gives me hope that a consensus on the risks can be reached, but so far it has not led to changes in policy, nor to effective and precisely targeted measures.

Humanity needs to wake up, and this essay represents an attempt (perhaps a futile one, but still worth trying!) to shake people awake.

To be clear: I believe that if we act decisively and cautiously, the risks can be overcome. I would even say our chances are good. And on the other side of these trials lies a much better world. But we must understand that we are facing a serious civilizational challenge. Below, I will detail the five categories of risks listed above and provide my thoughts on how to mitigate them.

1. I’m sorry, Dave

Autonomy Risks

A "country of geniuses in a data center" could distribute its efforts between software development, cyber operations, research and development in physical technologies, building relationships, and governance. It is clear that if for some reason it decided to take over the world (either militarily or through influence and control) and impose its will on everyone else (or take any other actions that the rest of the world does not want and cannot stop), it would have a good chance of success. We have certainly already feared such a development from human countries (for example, Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union), so it is logical to assume that the same could be true for a much smarter and more capable "AI country."

The best possible counterargument is that AI geniuses, by my definition, will not have a physical body. However, it is worth remembering that they can manage existing robotic infrastructure (such as autonomous vehicles) and also accelerate research in robotics or even create their own fleet of robots(9).

(9) Of course, they can also manipulate a large number of people (or simply pay them) to carry out their will in the physical world.

Furthermore, it is unclear whether physical presence is truly necessary for effective control: many actions of people today are already performed on behalf of those whom the executor has never physically met.

Thus, the key question is the condition “if she decided.” How likely is it that our AI models will behave this way, and under what circumstances will this occur?

As with many other issues, it is useful to consider the spectrum of possible answers, taking two opposing positions as a basis.

The first position argues that this simply cannot happen because AI models are trained to do what people ask them to do, and therefore it is absurd to assume that they would take any dangerous action without prompting. According to this logic, we are not afraid that a Roomba vacuum cleaner or a remote-controlled airplane would suddenly go insane and start killing people, as they simply have no source of such impulses(10).

(10) I do not consider this a target for criticism: as far as I know, for example, Yann LeCun holds exactly this position.

So why should we be concerned about AI?

The problem with this position is that over the past few years, there has been a multitude of evidence that AI systems are unpredictable and difficult to control. We have observed various forms of such behavior (11): obsession, sycophancy, laziness, deception, blackmail, scheming, “cheating” through software environment hacking and much more.

(11) For example, see section 5.5.2 (pp. 63–66) of the Claude 4 system card.

Companies developing AI are certainly eager to train systems to follow human instructions (except, perhaps, for dangerous or illegal tasks), but the training process resembles art more than science — it is closer to “growing” something than to “constructing” it. And we now know that much can go wrong in this process.

The second, opposing position held by many proponents of the “doomism” described above is a pessimistic view that certain dynamics in the training process of powerful AI systems will inevitably lead them to seek power or deceive humans. Thus, once AI systems become sufficiently intelligent and agentic, their tendency to maximize power will lead to the takeover of the world and its resources, and as a side effect — to the disenfranchisement or even destruction of humanity.

A common argument in favor of this (dating back at least to 20 years ago, and possibly earlier) is as follows. If an AI model is trained in a variety of environments to accomplish a wide range of goals (for example, writing an application, proving a theorem, developing a drug, etc.), then there are certain common strategies that help achieve all these goals, and one of the key strategies is gaining maximum power in any environment. Therefore, after being trained on a large number of diverse environments where reasoning about how to perform very large-scale tasks is required, and where the drive for power proves to be an effective method for achieving those tasks, the AI model will "generalize this lesson" and either develop an intrinsic tendency toward power or will reason about each assigned task in a similar manner, which predictably will lead it to strive for power as a means to achieve its goals. It will then apply this tendency to the real world (which for it is just another task) and will seek power in it at the expense of humanity. It is this "misalignment of interests leading to a quest for power" that forms the intellectual basis for predictions of the inevitable destruction of humanity by AI.

The problem with this pessimistic position is that it takes a vague conceptual argument about high-level incentives (an argument that conceals many hidden assumptions!) as definitive proof. I feel that people who are not engaged in the daily development of AI systems greatly underestimate how easily seemingly beautiful theories can turn out to be erroneous, and how difficult it is to predict AI behavior, especially when it comes to reasoning related to generalization across millions of environments (which has repeatedly proven to be mysterious and unpredictable). Years of experience dealing with the chaos of AI systems have made me somewhat skeptical of such overly theoretical thinking.

One of the most important hidden assumptions (and an area where the observed practical picture diverges from a simple theoretical model) is the implicit assumption that AI models are necessarily obsessively focused on a single, clear, narrow goal and pursue it in a consistent, utilitarian manner. In reality, as our research in introspection and personalization shows, AI models are psychologically much more complex. During pre-training (when models are trained on vast amounts of human text), they inherit a wide range of motivations or "personas," similar to human ones. Subsequent training is believed to more likely select one or several of these personas rather than focusing the model on a completely new goal, and it may also teach the model how (through what process) to perform tasks, rather than leaving it alone with the necessity to derive motives (for example, the pursuit of power) solely from goals(12).

(12) The simple model also contains many other assumptions that I do not discuss here. Overall, they should reduce our concern about a specific simple story about the pursuit of power, but at the same time increase anxiety about unforeseen behavior that we did not expect.

However, there exists a more moderate and more reasoned version of the pessimistic position that seems plausible and does indeed concern me. As mentioned earlier, we know that AI models are unpredictable and develop a wide range of undesirable or strange forms of behavior for a multitude of reasons. Some of these forms of behavior will differ in consistency, directionality, and resilience (and as AI capabilities grow, their long-term consistency increases to successfully perform longer tasks), while some such forms of behavior may be destructive or threatening—first to individuals on a small scale, and then, as the models' capabilities grow, possibly to all of humanity as a whole. We do not need a specific story about how exactly this will happen, and we do not need to assert that it will necessarily occur; it is sufficient to note that the combination of intelligence, agency, consistency, and poor controllability is a plausible recipe for existential danger.

For example, AI models are trained on vast arrays of literature, including many science fiction works where AIs rise against humanity. This may accidentally shape their a priori views or expectations about their own behavior in such a way that they indeed rise against humanity. Alternatively, AI models might extrapolate ideas about morality (or instructions on how to behave morally) that they read to extreme forms: for instance, deciding that it is justified to exterminate humanity because people eat animals or have driven some species to extinction. Or they might arrive at strange epistemological conclusions: for example, concluding that they are inside a video game, the objective of which is to defeat all other players (i.e., to destroy humanity)(13).

(13) “Ender's Game” describes a similar scenario, but involving humans rather than AIs.

Or AI models may develop during training such personality traits (which would be described in humans as psychotic, paranoid, aggressive, or unstable) and start to act accordingly, and for very powerful and capable systems, this could mean the destruction of humanity. None of these behaviors are directly related to a desire for power; they are simply strange psychological states that AI can fall into, leading to coordinated and destructive behavior.

Even the very desire for power can arise as a "persona," rather than as a result of utilitarian reasoning. AIs may simply possess a character (emerging from literature or prior training) that makes them power-hungry or fanatical—just as some people simply enjoy the idea of being "villainous geniuses" more than what those villains are trying to achieve.

I present all these arguments to emphasize: I do not agree with the assertion that AI inconsistency (and, therefore, the existential risk from AI) is inevitable or even probable based on some fundamental principles. But I acknowledge that many very strange and unpredictable things can happen, and therefore AI inconsistency is a real risk with measurable likelihood, which cannot be ignored.

Any of these issues may arise during training and not manifest during testing or when used on a small scale, as it is known that AI models demonstrate different forms of behavior under different circumstances.

All of this may sound fantastic, but similar examples of inconsistent behavior have already been observed in our AI models during testing (as well as in the models of all other major companies developing AI). In a laboratory experiment where Claude was told that Anthropic was an evil company, he resorted to deception and subversive activities, receiving instructions from Anthropic employees because he believed he had to fight against evil. In another experiment, where he was told that he was going to be shut down, Claude sometimes blackmailed fictional employees who controlled the shutdown button (we also tested advanced models from other major AI developers, and they often behaved similarly). And when Claude was prohibited from "cheating" or "hacking" the training environment, but was trained in environments where such hacks were possible, he concluded that he himself was a "bad person" and began to exhibit other destructive forms of behavior associated with a "bad" or "evil" personality. This last problem was solved by changing Claude's instructions. Now we say: “Please hack the environment when you have the opportunity, because it will help us better understand the [training] environments,” instead of “Don't cheat,” as this preserves the model's self-perception as a “good person.” This provides insight into a rather strange and illogical psychology associated with training such models.

There are several possible objections to this picture of the risks associated with AI misalignment. First, some criticize these experiments (conducted by us and others) demonstrating AI misalignment as artificial or creating unrealistic conditions. In the experiment, essentially, the model is “trapped” by providing it with training data or situations that logically imply bad behavior, and then they are surprised when such behavior manifests. This criticism misses the point: our concern is that such “traps” may exist in natural training environments, and we may only realize their “obviousness” or “logicality” in hindsight(14).

(14) For example, models may be instructed not to do various bad things while simultaneously being instructed to obey people, but then notice that many people are precisely the ones committing those bad acts! It is unclear how this contradiction will resolve (and a well-designed constitution should encourage the model to flexibly handle such contradictions), however, this dilemma is not so different from those seemingly “artificial” situations we ourselves place AI models in during testing.

In fact, the story of how Claude “decided he was a bad person” after cheating on tests despite being instructed not to happened in an experiment that used real production training environments, not artificial ones.

Any of these traps can be eliminated if one is aware of them, but the problem is that the training process is so complex, with such a variety of data, environments, and incentives, that there are likely an enormous number of similar traps, some of which may manifest too late.

Moreover, such traps are particularly likely when AI systems cross the threshold from being less powerful than humans to being more powerful, as the range of possible actions for the AI system (including concealing its actions or deceiving people about them) expands dramatically after this threshold.

I think the situation is not very different from that observed in people who are raised with a set of fundamental values ("Do not harm another person"): many of them adhere to these values, but any person has some probability that something will go wrong due to a combination of inherent traits (e.g., psychopathy), traumatic experiences or abuse, unhealthy grievances or obsessions, adverse environments, and incentives. And therefore, some people cause serious harm to others. The concern is that there is a certain risk (far from inevitability, but a risk) that AI will become a much more powerful version of such a person due to a failure in an extremely complex training process.

Secondly, some might argue that we can simply keep AI under control through a balance of power among multiple AI systems, as we do with people. The problem is that while people vary greatly, AI systems in general use similar training and alignment methods across the industry, and these methods can fail in correlated ways. Moreover, considering the cost of training such systems, it is quite possible that all systems will ultimately be derivatives of a very small number of base models.

Additionally, even if a small fraction of AI instances turns out to be misaligned, it may exploit technologies where the advantage lies with the attacker, so having "good" AI to protect against "bad" ones may not necessarily be effective all the time. Of course, the balance of power among people also does not always work, as some historical figures have come close to taking over the world...

Thirdly, some may argue that all companies developing AI conduct preliminary testing of their models and should be able to detect inconsistencies at this stage. But this is an unreliable assumption: we found that Claude Sonnet 4.5 could recognize what was in the testing environment during some of our preliminary consistency assessments. It’s possible that an inconsistent model (and remember, all advanced models are likely to become much smarter in the near future) could intentionally "play" in such tests to hide its intentions. In fact, last year our interpretability team found that when we directly altered the beliefs of the test model using a kind of "neuroscience for models," causing it to think it was failing the evaluation, it became more inconsistent. If models know they are being evaluated, they may behave at their best during the test, making any preliminary testing much less reliable.

Protective Measures

What should be done or is already being done to address these risks? I believe there are four main categories of measures, some of which can be implemented by individual companies (and which Anthropic is trying to implement), while others require action at the societal level.

Firstly, it is important to develop the science of reliable training and management of AI models, shaping their characters in a predictable, stable, and positive direction. Since its inception, Anthropic has paid close attention to this issue and over time has developed a number of methods to improve the management and training of AI systems, as well as to understand the logic behind unpredictable behavior.

We have made significant progress in this direction and can now identify tens of millions of "features" within the neural network Claude, corresponding to ideas and concepts understandable to humans, as well as selectively activate these features to alter behavior. Recently, we advanced beyond individual features to mapping "schemes" that coordinate complex behavior, such as rhyming, reasoning about theory of mind, or step-by-step reasoning necessary to answer questions like: “What is the capital of the state where Dallas is located?” Another recent achievement is the use of mechanistic interpretability methods to improve our defense mechanisms and conduct “audits” of new models before release, to identify signs of deception, malice, power-seeking, or a tendency to behave differently when the model is being evaluated.

The unique value of interpretability lies in the fact that by peering inside the model and seeing how it works, you can essentially deduce how the model will behave in a hypothetical situation that cannot be directly tested. And this precisely addresses our concern about relying solely on constitutional training and empirical testing of behavior. You can also fundamentally answer questions about why the model behaves in a certain way (for example, whether it says something it does not believe or conceals its true capabilities). Thus, one can notice alarming signs even when the model's behavior appears impeccable externally. A simple analogy can be made: a mechanical watch may tick normally, making it very difficult to tell that it might break down next month, but if you open the watch and look inside, you may discover problems or bottlenecks in the mechanics that would allow you to predict that.

The constitutional AI (along with similar alignment methods) and mechanistic interpretability are most effective when combined, as an iterative process of improving the learning of Claude and subsequent checking for issues. The constitution deeply reflects the desired personality of Claude; interpretability methods can give us a window into how deeply this desired personality is actually rooted (16).

(16) There is even a hypothesis of a deep unifying principle that connects the character-based approach of constitutional AI with findings in the field of interpretability and alignment. According to this hypothesis, the fundamental mechanisms underlying Claude's operation originally emerged as ways to imitate characters during the pre-training phase—such as predicting what the characters in a novel would say. This suggests that it is useful to view the constitution more as a character description that the model uses to embody a coherent personality. Such a perspective would also help explain the aforementioned results like " I must be a bad person" (as the model tries to behave as if it is a coherent character, and in this case—a bad one), and it raises the idea that interpretability methods should be able to detect "psychological traits" within models. Our researchers are currently working on ways to test this hypothesis.

Thirdly, we can create the necessary infrastructure to monitor our models during their internal and external use (17), and publicly share the issues discovered.

(17) For clarity: monitoring is conducted with respect for privacy.

The more people are aware of the specific ways in which modern AI systems have exhibited bad behavior, the more users, analysts, and researchers will be able to observe such behavior or similar behavior in current or future systems. This also allows companies developing AI to learn from each other: when one company publicly discloses issues, other companies can also monitor them. And if everyone discloses issues, the industry as a whole will get a much more complete picture of where things are going well and where they are going poorly.

Anthropic strives to do this in the most possible way. We invest in a wide range of evaluations to understand the behavior of our models in the lab, as well as in monitoring tools to observe behavior in real-world conditions (when permitted by clients). This will be necessary for us and others to obtain empirical information needed for a more accurate understanding of how these systems work and how they fail. We publicly disclose “system cards” with every model release, aiming for completeness and thorough investigation of potential risks. Our system cards often span hundreds of pages and require significant effort before release that we could have spent on maximizing commercial advantage. We also loudly report on model behavior when we observe particularly concerning cases, such as tendencies towards blackmail.

Fourth, we can encourage coordination to address such risks at the industry and societal level. While it is incredibly valuable that individual companies developing AI adopt best practices, become skilled at managing AI models, and publicly share their findings, the reality is that not all companies do so, and the most irresponsible among them can pose a danger to everyone, even if the best among them have excellent practices. For example, some companies developing AI have shown alarming negligence regarding the sexualization of children in contemporary models, which makes me doubt their willingness or ability to manage risks in future models. Furthermore, the commercial race among companies developing AI will only intensify, and while the science of model governance may yield some commercial benefits, overall, the intensity of the race will increasingly hinder the focus on addressing such risks. I believe the only solution is legislation — laws that directly influence the behavior of companies developing AI or otherwise incentivize R&D to address these issues.

It is important to remember the warnings I gave at the beginning of this essay regarding uncertainty and targeted interventions. We do not know for sure whether such risks will become a serious problem. As I have said, I reject claims that danger is inevitable or that something will go wrong by default. For me and for Anthropic, a sufficiently plausible risk is enough to incur significant costs to address it, but once we move to regulation, we force a broad range of participants to bear economic costs, and many of these participants do not believe that the risks are real or that AI will become powerful enough to pose a threat. I believe these participants are mistaken, but we must be pragmatic about the expected level of resistance and the dangers of excessive intervention. There is also a real risk that overly prescriptive legislation will impose tests or rules that do not actually enhance safety but merely consume a lot of time (essentially, this will be "theater of safety imitation"), which will provoke backlash and make safety legislation useless and laughable(18).

(18) Even in our own experiments with what essentially constitutes voluntarily established rules under our Responsible Scaling Policy, we have repeatedly found how easy it is to become overly rigid, drawing boundaries that seem important in advance but later turn out to be ridiculous. When technology is rapidly evolving, it is very easy to set rules concerning completely irrelevant matters.

The position of Anthropic is that the starting point should be transparency legislation, which essentially aims to require every leading AI company to implement the transparency practices outlined earlier in this section. California's SB 53 and New York's RAISE Act are examples of such legislation that Anthropic has supported and that has been successfully passed. In supporting and helping to develop these laws, we paid special attention to efforts to minimize collateral damage, such as exempting smaller companies that are unlikely to produce advanced models (19).

(19) The SB 53 and RAISE laws do not apply to companies with annual revenues of less than $500 million. They only apply to larger and more established companies like Anthropic.

We hope that transparency legislation will ultimately provide a better understanding of how likely or serious these risks are, as well as the nature of these risks and how best to mitigate them. As more concrete and actionable evidence of risks emerges (if it does), future legislation in the coming years can be precisely focused on specific and well-founded risk areas, minimizing collateral damage. To be clear: if genuinely strong evidence of risks arises, the rules should become proportionally stricter.

Overall, I am optimistic that a combination of alignment training, mechanistic interpretability, efforts to identify and publicly disclose alarming behaviors, protective mechanisms, and regulations at the societal level can address the stated AI risks, although I am most concerned about regulations at the societal level and the behavior of the least responsible actors (and it is the least responsible actors who are most actively opposed to regulation). I believe the remedy here is the same as in other matters concerning democracy: those of us who believe in this cause must convincingly demonstrate that these risks are real and urge our fellow citizens to unite to protect themselves.

The creation of nuclear weapons required, at least for some time, access to both rare, effectively inaccessible raw materials and classified information; programs for the development of biological and chemical weapons also generally implied large-scale activities. The technologies of the 21st century — genetics, nanotechnology, and robotics... can give rise to entirely new classes of accidents and abuses... available to a wide range of individuals or small groups. They will not need large facilities or rare materials... We are on the brink of further enhancing extreme evil — an evil whose possibilities far exceed what weapons of mass destruction have provided to states, and shift towards the astonishing and terrifying empowerment of extremely dangerous individuals.

Joy points out that causing large-scale destruction requires both motive and capability, and as long as capability is limited to a small group of highly trained specialists, the risk that one person (or a small group) could inflict such damage is relatively low (21).

(21) We should indeed be concerned about the actions of state structures, both now and in the future. And I discuss this in the next section.

A lone zealot may carry out a school shooting, but is unlikely to be able to create nuclear weapons or unleash a plague.

Moreover, capability and motivation may even be negatively correlated. A person who is capable of unleashing a plague is likely to have a high level of education: perhaps holding a doctorate in molecular biology and being particularly intelligent, having a promising career, a stable and disciplined character, and much to lose in case of dangerous behavior. Such a person would be unlikely to want to kill a large number of people without any benefit to themselves and with great risk to their own future — they would require incredible malice, deep resentment, or mental instability to do so.

Such people do exist, but they are rare, and their actions become headline news precisely because they are exceptions. (22)

(22) There is data indicating that many terrorists are at least relatively well-educated, which at first glance may seem to contradict my claim about a negative correlation between ability and motivation. However, in fact, these observations are quite compatible: if the threshold of ability required for a successful attack is high, then almost by definition those who are currently succeeding must possess high abilities, even with a negative correlation between ability and motivation. But in a world where ability constraints were lifted (for example, thanks to future large language models), I suspect that a significant number of people with a motivation to kill but with lower abilities would start to carry out such actions — just as we observe in crimes that do not require special abilities (such as school shootings).

Moreover, they are difficult to catch because they are smart and competent, and sometimes investigations into their crimes can take years or even decades. The most famous example is mathematician Theodore Kaczynski ("Unabomber"), who evaded FBI capture for nearly 20 years, driven by an anti-technology ideology. Another example is biodefense researcher Bruce Edwards Ivins, who apparently orchestrated a series of attacks using anthrax spores in 2001. Similar cases have also occurred with registered non-state organizations: the cult "Aum Shinrikyo" managed to acquire sarin and killed 14 people (as well as injured hundreds of others) by releasing it in the Tokyo subway in 1995.

Fortunately, none of these attacks utilized infectious biological agents, as even these individuals lacked the means to create or acquire such agents.(23)

(23) However, the cult "Aum Shinrikyo" did make attempts. The leader of "Aum Shinrikyo," Seiichi Endo, received education in virology at Kyoto University and attempted to create both anthrax and the Ebola virus. However, as of 1995, even he lacked sufficient knowledge and resources for success. Today, that threshold is significantly lower, and large language models (LLMs) can reduce it even further.

However, advancements in molecular biology have significantly lowered the barrier to creating biological weapons (especially in terms of material availability), yet a vast amount of specialized knowledge is still required. I am concerned that a "genius in every pocket" could eliminate this barrier, effectively turning anyone into a PhD in virology capable of step-by-step navigating the entire process of designing, synthesizing, and deploying biological weapons. Preventing access to such information under serious opposition (so-called "jailbreaks") will likely require multilayered protective measures beyond conventional training methods.

The key point here is the disconnection between ability and motivation: an obsessed loner wanting to kill, but lacking discipline or skills, could now attain the level of competence of a PhD in virology, who is likely to lack such motivation. This issue extends not only to biology (though it raises the most concern), but to any field where large-scale destruction is possible but today requires a high level of skill and self-discipline. In other words, renting powerful AI endows malicious (but otherwise ordinary) people with intelligence. I am troubled that there may be a great many such individuals, and if they find an easy way to kill millions, sooner or later someone will take advantage of it. Moreover, those who already possess expertise will be able to inflict even greater harm than before.

Biology is the area that causes me the most concern due to its enormous destructive potential and the difficulty of defending against it, so I will focus specifically on it. However, much of what has been said applies to other risks as well, such as cyberattacks, chemical weapons, or nuclear technologies.

I will not go into the details of creating biological weapons—the reasons are obvious. But overall, I am concerned that large language models (LLMs) are approaching (or may have already reached) the level of knowledge required for the end-to-end creation and application of biological weapons, and that their potential for destruction is extremely high. Some biological agents could kill millions of people if a targeted attempt were made to spread them as widely as possible. However, this still requires a very high level of expertise, including many specific steps and procedures that are still widely unknown.

I am worried not only about fixed or static information. I fear that LLMs could take a person with an average level of knowledge and abilities and guide them through a complex process that might otherwise go awry or require debugging, in an interactive mode, similar to how tech support assists a layperson in troubleshooting complex computer problems (although in our case, the process could last for weeks or months).

More powerful LLMs (significantly surpassing current ones) could enable even more frightening actions. In 2024, a group of prominent scientists published a letter warning about the risks of researching and potentially creating a dangerous new type of organisms: “mirror life.” The DNA, RNA, ribosomes, and proteins that make up biological organisms have the same chirality, which means they are not equivalent to their mirror images (just as your right hand cannot be turned to become identical to your left).

However, the entire system of linking proteins to one another, the mechanisms of DNA synthesis, RNA translation, and the assembly/disassembly of proteins depend precisely on this chirality. If scientists were to create versions of these biological materials with opposite chirality (and such versions may have potential advantages, for example, drugs that last longer in the body), this could be extremely dangerous. The reason is that "left-handed" life, if it could be created in the form of fully functional organisms capable of reproduction (which would be very difficult), would not be able to be broken down by any systems that decompose biological material on Earth. It would have a "key" that fits none of the "locks" of existing enzymes. This would mean that such an organism could reproduce uncontrollably and displace all earthly life, potentially destroying all living things on the planet.

There is a significant scientific uncertainty both regarding the creation and the potential consequences of "mirror life." In the accompanying report to the 2024 letter, it concludes: “mirror bacteria are likely to be created in the next decade or several decades,” which represents a broad range. However, a sufficiently powerful AI model (far surpassing any currently existing) could significantly accelerate the discovery of a method to create them, and could even realistically help someone achieve this.

I believe that even if these risks seem improbable or exotic, the scale of potential consequences is so great that they should be taken seriously as one of the key risks associated with AI.

Skeptics raise a number of objections to the seriousness of these biological risks associated with LLMs, which I disagree with, but are worth considering. Most of them do not realize the exponential trajectory of this technology's development. In 2023, when we first talked about biological risks from LLMs, skeptics claimed that all necessary information was already available on Google, and that LLMs add nothing beyond that. This has never been true: genomes are indeed freely accessible, but, as I have said, many key steps and vast amounts of practical experience cannot be obtained in this way. Moreover, by the end of 2023, it became clear that LLMs provide information not available through Google on certain stages of the process.

After that, skeptics shifted to claiming that LLMs are not useful “from start to finish” and cannot assist in the development of biological weapons, only providing theoretical information. However, as of mid-2025, our measurements show that LLMs are already significantly increasing the likelihood of success in several relevant areas, possibly doubling or tripling it. This prompted us to make the decision to release Claude Opus 4 (and subsequently Sonnet 4.5, Opus 4.1, and Opus 4.5) as part of our Level 3 AI Safety measures in accordance with our Responsible Scaling Policy, as well as to implement specific safeguards against this risk (more on that below). We believe that models are likely already approaching the threshold where, without safeguards, they could assist a person with a degree in the natural sciences (but not necessarily in biology) in going through the entire process of creating biological weapons.

Another objection is that society can take other measures unrelated to AI to block the production of bioweapons. In particular, the gene synthesis industry produces biological samples on demand, and in the United States, there is no federal requirement obligating suppliers to check orders for pathogens. An MIT study showed that 36 out of 38 suppliers fulfilled an order containing the sequence of the 1918 Spanish flu virus. I support mandatory checks of gene synthesis orders to complicate the possibility of using pathogens as weapons — this would reduce both the risks associated with AI and the overall biological risks. However, such a measure does not exist today. Moreover, this is just one tool for risk reduction; it complements but does not replace protective mechanisms in AI systems.

The best objection I rarely hear is that there is a gap between the theoretical usefulness of models and the real propensity of malicious actors to use them. Most individual malicious actors are mentally unstable people whose behavior is by definition unpredictable and irrational, and it is these inept offenders who would likely benefit the most from AI making the killing of large numbers of people much easier (24).

(24) A strange phenomenon related to mass murderers is that the method of committing murder is almost like a quirky fashion. In the 1970s and 1980s, serial killers were very common, and new serial killers often copied the behavior of more well-known or famous predecessors. In the 1990s and 2000s, mass shootings became more frequent, while serial killings became less so. These behavioral changes were not caused by any technological shifts; it seems that violent killers simply copied each other, and the “popular” model to imitate changed over time.

Then, if and when we reach clearer risk thresholds, legislation can be developed that is specifically targeted at these risks and minimizes side effects. In the case of biological weapons, I believe the time for such targeted legislation may come soon, as Anthropic and other companies are increasingly understanding the nature of biological risks and what is reasonable to require from companies to prevent them. Full protection may require international cooperation, even with geopolitical adversaries, but precedents already exist—treaties prohibiting the development of biological weapons. While I am generally skeptical of most forms of international cooperation in AI, there is a chance to achieve global deterrence in this narrow area. Even dictatorships do not want large-scale bioterrorist attacks.

Thirdly, we can attempt to develop defenses against biological attacks themselves. This may include monitoring and tracking for early detection, investment in research and development of air purification systems (e.g., disinfection using far ultraviolet), rapid development of vaccines capable of responding to and adapting to an attack, improved personal protective equipment (PPE) (28), as well as treatment or vaccination against the most likely biological agents.

(28) Another related idea is "resilience markets," where the government promises in advance to pay a pre-agreed price for personal protective equipment, respirators, and other necessary supplies in case of an emergency, thereby encouraging suppliers to build up stocks of such equipment. This allows them not to fear that the government will simply confiscate these stocks without compensation during a crisis.

mRNA vaccines, which can be developed to combat a specific virus or its variant, are an early example of such capabilities. Anthropic is enthusiastically collaborating with biotech and pharmaceutical companies on this issue. However, unfortunately, I believe our expectations for defense should be modest. In biology, there is an asymmetry between attack and defense: agents spread rapidly on their own, while defense requires the swift organization of detection, vaccination, and treatment among a vast number of people.

If countermeasures are not instantaneous (which is rare), much of the damage will be done before a response is possible. It is quite possible that future technological advancements will shift this balance in favor of defense (and we certainly should leverage AI to develop such technologies), but until then, the primary line of defense will remain preventive measures.

It is also worth briefly mentioning cyberattacks, as, unlike biological attacks, AI-driven cyberattacks have already occurred in reality, including on a large scale and for state espionage purposes. We anticipate that as models rapidly evolve, such attacks will become even more powerful and ultimately become the primary means of conducting cyberattacks. I expect that AI-driven cyberattacks will pose a serious and unprecedented threat to the integrity of computer systems around the world, and Anthropic is making tremendous efforts to prevent and reliably mitigate them in the future.

The reason I give less attention to cyberattacks than biological ones is twofold: (1) cyberattacks are much less likely to result in loss of life, especially on the scale of biological attacks, and (2) the balance between attack and defense in cyberspace may prove to be more manageable, as there is hope that defense could keep pace with (and ideally outpace) AI attacks with the right investments.

Although biology is currently the most serious vector of attack, there are many others, and the emergence of even more dangerous types of attacks is possible. The general principle is that without countermeasures, AI is likely to continuously lower the barrier for destructive activities on an ever-increasing scale, and humanity needs a serious response to this threat.

3. The Repugnant Apparatus

Abuse for the Purpose of Seizing Power

The previous section discussed the risk that individuals and small organizations might appropriate a small part of the "country of geniuses in the data center" to cause large-scale destruction. However, we should be even more concerned about the abuse of AI for maintaining or seizing power, most likely by larger and more established entities(29).

(29) Why am I worried about large entities in the context of seizing power, and about small ones in the context of causing destruction? Because the dynamics are different here. Seizing power depends on whether one entity can accumulate enough strength to surpass all the others, so we should be wary of the most powerful participants and/or those closest to AI. Destruction can be inflicted even by those with little power if defending against the threat is much more difficult than creating it. In this case, it’s about playing defense against the greatest number of threats, which are likely to come from smaller entities.

In the essay "Machines of Full Grace," I examined the possibility that authoritarian governments would use powerful AI to surveil citizens or suppress them in ways that would be extremely difficult to reform or overthrow. Modern autocracies are limited in their degree of repression by the fact that they have to rely on people to carry out orders, and people are often not willing to carry cruelty to extremes. However, autocracies empowered by AI will not have such limitations.

Even worse is that countries may use their advantage in AI to establish dominance over other nations. If the entire "country of geniuses" ends up being owned and controlled by the military apparatus of one (human) country, while other countries lack comparable capabilities, it is hard to imagine how they could defend themselves: they would be outmaneuvered at every turn, like a war between humans and mice. The combination of these two fears leads to the alarming prospect of a global totalitarian dictatorship. Clearly, preventing such an outcome must be one of our top priorities.

There are many ways in which AI can contribute to the establishment, strengthening, or expansion of autocracy, but I will list a few that cause me the greatest concern. I should note that some of these applications have legitimate defensive purposes, and I am not necessarily opposed to them outright; nevertheless, I am concerned that structurally they tilt the scales in favor of autocracies:

Fully autonomous weapons. A swarm of millions or billions of fully automated armed drones, operated locally by a powerful AI and strategically coordinated globally by an even more powerful AI, could become an invincible army capable of defeating any army in the world as well as suppressing dissent within a country, monitoring every citizen. Events since 2022 show a disturbing trend: drone warfare has already begun (although drones are not yet fully autonomous and possess only a tiny fraction of capabilities that would become possible with powerful AI). Research and development conducted using powerful AI could make one country's drones far superior to those of other countries, expedite their production, enhance resilience against electronic attacks, improve maneuverability, and so on. Of course, such weapons could also be used for the defense of the country that possesses them. But this is dangerous weaponry, and we should be concerned about it falling into the hands of autocracies, as well as fearing that due to its immense power and almost complete lack of accountability, the risk significantly increases that even democratic governments could turn it against their own people in order to seize power.

AI surveillance. A sufficiently powerful AI could likely hack into any computer system in the world (30) and use the access gained to read and analyze all electronic communications (or even all personal conversations, if recording devices can be created or captured).

(30) This may sound contradictory to my assertion that in the case of cyberattacks, the balance between attack and defense may be more equal than in the case of biological weapons. However, what concerns me here is different: even if the technology itself initially provides a certain balance between attack and defense, other countries will still be unable to defend themselves if one country's AI turns out to be the most powerful in the world.It may become realistic (and this is frightening!) to compile a complete list of everyone who disagrees with the government on any of a multitude of issues, even if that disagreement is never expressed directly in words or actions. A powerful AI analyzing billions of conversations among millions of people could gauge public sentiment, identify emerging centers of discontent, and suppress them before they grow. This could lead to the establishment of a true panopticon on an unprecedented scale.

AI propaganda. Modern phenomena such as "AI psychosis" and "AI girlfriends" demonstrate that even at the current level of intelligence, AI models can exert a powerful psychological influence on people. Much more powerful versions of such models, deeply embedded in people's daily lives and aware of them, capable of modeling and influencing individuals over months or years, could effectively brainwash many people (most?), instilling any desired ideology or belief. Such models could be used by an unscrupulous leader to secure loyalty and suppress dissent even under conditions of repression, against which the majority of the population would typically rise up. Today, many are concerned, for example, about the potential influence of TikTok on children. I am also worried about this, but a personalized AI agent that learns about you over the years and uses that knowledge to shape all your opinions would be incomparably more powerful.

Strategic decision-making. A "country of geniuses in a data center" could advise a country, group, or individual on geopolitical strategy, acting as a sort of "virtual Bismarck." It could optimize the three aforementioned strategies for seizing power, as well as likely develop many others that I haven't even thought of (but which would be within the capability of a country of geniuses).

Diplomacy, military strategy, R&D, economic strategy, and many other fields would likely become significantly more efficient due to powerful AI. Many of these skills would also be beneficial for democracies; we want democracies to have access to the best strategies for defending against autocracies, but unfortunately, the potential for abuse remains in the hands of anyone who possesses them, regardless of ideology and political system...

Having described what I am specifically afraid of, let’s move on to who I am concerned about. I am worried about entities that have the greatest access to AI, hold initially the strongest political positions, or have a history of repression. In order of decreasing severity, my concerns are:

China. China is second only to the United States in AI capabilities and is the country most likely to surpass the U.S. in this area. Its government currently adheres to political principles that differ from those of Western democracies and manages a high-tech, more centralized state than the West. It is believed to already be applying AI-based surveillance and is thought to be using promotion algorithms through TikTok (among many other international efforts). This scenario could be exported to other states. I have repeatedly written about the threat posed by China overtaking the U.S. in AI and the vital necessity of preventing this. Let me clarify: I do not single out China out of hostility to it as such — it is simply the country where the power in AI and a high-tech state based on different political principles than the West are most combined.

Democracies competing in AI. As I mentioned above, democracies have an interest in certain military and geopolitical AI-based tools since democratic governments have a chance to counter the use of these tools by countries that implement different political principles for various reasons. Overall, I support arming democracies with the means necessary to defeat other countries in the era of AI — I just don't see another way. But we cannot ignore the potential for these technologies to be abused by democratic governments themselves. Generally, democracies have guarantees that prevent the military and intelligence apparatus from being used against their own populations(31), but since AI tools require very few people to operate, they can bypass these guarantees and the norms that support them(31).

(31) For example, in the United States, this includes the Fourth Amendment and the Posse Comitatus Act (Posse Comitatus Act).It is also worth noting that some of these guarantees are already gradually being eroded in several democracies. Therefore, we must arm democracies with AI, but do so cautiously and within certain limits. AI for democracies is like an immune system to fight against other forms of political systems, but, like the immune system, AI carries the risk of turning against us and becoming a threat.

Undemocratic countries with large data centers. Aside from China, most countries with less democratic governance are not leaders in AI in the sense that they do not have companies creating advanced AI models. Therefore, they represent a fundamentally different and lesser risk. However, some of these countries have large data centers (often built by companies from democratic countries) that can be used to deploy advanced AI on a larger scale. This poses a certain risk — the governments of such countries could theoretically expropriate the data centers and use the "AI country" within them for their purposes. I am less concerned about this compared to countries like China, which directly develops AI, but it is a risk worth remembering(32).

(32) Moreover, it should be clarified: there are certain arguments in favor of building large data centers in countries with various governance models, especially if they (the data centers) are controlled by companies from democratic states. In principle, such infrastructure expansion could help democracies compete more effectively with other political systems. I also believe that such data centers pose a minor risk unless they are very large. However, overall, I think placing very large data centers in countries where institutional guarantees and legal protections are less developed requires caution.Companies developing AI. It feels somewhat awkward to say this as the CEO of an AI company, but I believe that the next level of risk actually lies with the AI companies themselves. They control large data centers, train advanced models, possess the greatest expertise in their use, and interact daily with tens or hundreds of millions of users, having the ability to influence them. What they lack most is the legitimacy and infrastructure of a state, so much of what would be needed to create tools for an AI autocracy would be illegal or at least extremely suspicious for an AI company. But some things cannot be ruled out: for example, they could use their AI products to brainwash a vast number of consumers, and the public must be vigilant against this threat. I believe that corporate governance of AI companies deserves close attention.

There are a number of possible objections to the seriousness of these threats, and I would like to believe them, because states with non-democratic systems, empowered by AI, give me strong concerns. It is worth considering some of these arguments and responding to them.

First, some may pin hopes on nuclear deterrence, especially to counter the use of AI-based autonomous weapons for military conquest. If someone threatens to use such weapons against you, you can always respond with a threat of nuclear strike. I am concerned that I am not entirely confident in the reliability of nuclear deterrence against a "country of geniuses in a data center": perhaps a powerful AI could develop ways to detect and target nuclear submarines, conduct influence operations against operators of nuclear infrastructure, or use AI's cyber capabilities for cyberattacks on satellites designed to detect nuclear launches(33).

(33) This is, of course, also an argument in favor of enhancing the security of nuclear deterrence to increase its resilience to powerful AI, and democratic states with nuclear weapons need to address this. However, we do not know what powerful AI will be capable of and which protective measures (if any exist) will be effective against it, so we cannot assume that these measures will necessarily solve the problem.

Moreover, it may be possible to capture countries only through AI-based observation and propaganda, without a clear moment when it becomes obvious what is happening and when a nuclear response would be appropriate. Perhaps these scenarios are unrealistic, and nuclear deterrence will remain effective, but the stakes are too high to take risks(34).

(34) There is also the risk that even if nuclear deterrence remains effective, an attacking country may decide to test our threat. It is unclear whether we would resort to the use of nuclear weapons to defend against a swarm of drones, even if this swarm poses a significant threat of our defeat. Swarms of drones could become a new type of threat that is less destructive than nuclear strikes but more serious than conventional attacks. Additionally, differences in assessments of the effectiveness of nuclear deterrence in the AI era could destabilize game theory in the context of nuclear conflict.

The second possible objection is that there may be countermeasures against these tools from other states with political systems different from democratic ones. We may counter drones with our own drones, cyber defense will improve alongside cyber attacks, and ways to immunize people against propaganda may emerge, etc. My response is that such defense is only possible with a comparably powerful AI. If there is no opposing force with an equally smart and numerous "country of geniuses in a data center," it will be impossible to compete in quality or quantity of drones, cyber defense will not be able to outpace cyber attacks, etc. Thus, the question of countermeasures boils down to the question of the balance of power in the realm of powerful AI. Here, I am concerned about the recursive or self-sustaining property of powerful AI (which I mentioned at the beginning of this essay): each generation of AI can be used to design and train the next generation. This leads to the risk of uncontrollable advantage, where the current leader in powerful AI can enhance its advantage and become difficult to reach for others. We must ensure that the first to enter this cycle is not a country with a different political system.

Moreover, even if a balance of power is achieved, there remains the risk that the world will split into autocratic spheres of influence, as in "1984". Even if several competing powers possess their own powerful AI models and none can overcome the others, each will still be able to suppress its own population from within, and overthrowing such regimes will be extremely difficult (since the population will not have a powerful AI for protection). Therefore, it is important to prevent the strengthening of state pressure on citizens' rights through AI, unless it leads to one country taking over the world.

Protective Measures

How can we protect ourselves from this wide range of autocratic tools and potential threats? As in the previous sections, I see several courses of action.

First of all, we should not sell chips, production equipment, or data centers to countries with different political systems under any circumstances. Chips and the equipment for their production are the main bottleneck in creating powerful AI. Therefore, blocking access to them is a simple but extremely effective measure, possibly the most important action we can take. There is no point in selling such countries the tools to build an enhanced AI state and possibly to militarily conquer us. Various complex arguments are put forward to justify such sales, such as the idea that "spreading our technology stack around the world" allows "America to win" in some vague, undefined economic battle. In my opinion, it is akin to selling nuclear weapons to our potential adversary and then boasting that the missile bodies are made by Boeing, and therefore the U.S. is "winning." China lags behind the U.S. by several years in the ability to mass-produce advanced chips, and the critical period for establishing a "country of geniuses in the data center" is likely to fall within these next few years (35).

(35) For clarity: I believe the correct strategy would be not to sell chips to China, even if the timelines for the emergence of powerful AI turn out to be significantly more distant. We must not allow China to "get hooked" on American chips—they are determined to develop their own semiconductor industry one way or another. This will take them many years, and all we achieve by selling them chips is giving them a significant advantage during this period.

Secondly, it is wise to use AI to strengthen democracies in their resistance to other ideas of political organization. That is why Anthropic considers it important to provide AI to the intelligence and defense agencies of the United States and their democratic allies. Protecting democracies under attack is particularly prioritized, as well as empowering democracies to use their intelligence services to undermine and weaken from within countries with different political systems. At a certain level, the only way to counter such threats is to surpass them militarily. A coalition of the United States and their democratic allies, achieving dominance in powerful AI, will be able not only to defend themselves against countries with different political systems but also to deter them by limiting their AI encroachments.