- DIY

- A

Electrovacuum getters. General provisions, classification, first gas absorbers

After examining gas absorption and gas release in electrovacuum materials, we reached an inevitable and disappointing conclusion: without significant work on cleaning and extracting gases from metals, glass, mica, and ceramics in radio lamps, the lifespan of finished devices will be quite short, and parameters unsatisfactory. The special element in the lamp — the gas absorber, or getter, binds undesirable gases, significantly extending the life of electrovacuum devices and stabilizing their electrical characteristics. Essentially a local miniature disposable high-vacuum pump, the getter allows for quick and relatively shallow pumping during the mass production of lamps, dramatically reducing production costs and the price of finished devices. So how does a getter work, what types are there, and what getters were used in incandescent lamps and some early electronics?

1. Absorption mechanisms, terms

There are several mechanisms for gas absorption by solid bodies, one or another of which predominates depending on the circumstances, type of material, and gas [2].

Chemical interaction with gas or vapor is called chemisorption. For example, titanium reacts with oxygen and nitrogen, forming stable solid compounds—oxides, nitrides—with low vapor pressure.

A gas can condense on the surface of a solid body, forming a film one or several molecules thick. This process is called adsorption, and the solid substance is referred to as the adsorbent. Since adsorption is limited to a monomolecular layer, the best adsorbents will be porous substances with a high specific surface area—activated carbon, silica gel, highly dispersed oxides, and metals.

Gas can also penetrate into the solid body, dissolving in it, similar to how gases dissolve in liquids. This phenomenon is called absorption. It often happens that gas in a solid body exists in both adsorbed and absorbed states simultaneously, while in other cases, it becomes difficult to accurately establish the absorption mechanism, which is why both concepts are often combined under the more general term — sorption.

Different solid bodies vary greatly in their ability to absorb gases and vapors. With an increase in temperature, the solubility of gases in metals (absorption) increases, while adsorption decreases.

2. Which gases will the getter have to work with?

Modern highly efficient oxide cathodes-emitters, as well as photocathodes, are very sensitive even to minute amounts of chlorine ions, fluorine, sulfur, phosphorus, nitrogen oxide radicals; therefore, for example, the processes of cleaning and etching materials for such devices are usually performed without the use of mineral acids [3], the traces of which inevitably end up in the vacuum.

Culturally organizing the preparation of materials, one can speak of a set of gases that the getter usually has to deal with — N2, CO, CO2, N2, O2, and steams H2O. Among them, all except the reducing hydrogen and neutral nitrogen are literally toxic to oxide and photocathodes, while the steams of water with hot tungsten create a continuous cycle of its transfer to the bulb (directly heated tungsten cathodes, incandescent lamps).

The main source of gases in receiving-amplifying lamps (RAL) is the cathode and anode — electrodes that have the greatest mass and operating temperature.

3. Requirements for ideal gas absorbers

The substance used as a getter must more or less meet a number of specific requirements:

low vapor pressure (no more than 10-3-4 mm Hg (Torr)) during the thermal treatment of the device (during the sealing of the bulb, heating during pumping),

significant evaporation rate for sprayable variants,

the gas absorption rate of the getter must exceed the total outgassing and influx of gases in the device,

the partial pressure of the most active gases and vapors in the vacuum envelope during operation (after operation) of the getter must not exceed 10-7-9 (Torr),

the residual atmosphere in the device should predominantly consist of inert, neutral, or reducing gases,

the gas absorbent must securely retain absorbed gases and vapors and not release them under thermal, mechanical, and electrical overloads, for example, during heating, ion and electron bombardment of the gas absorbent, and device vibration.

4. Classification of Gas Absorbents [5]

Usually, getters are divided into two major classes based on their method of application:

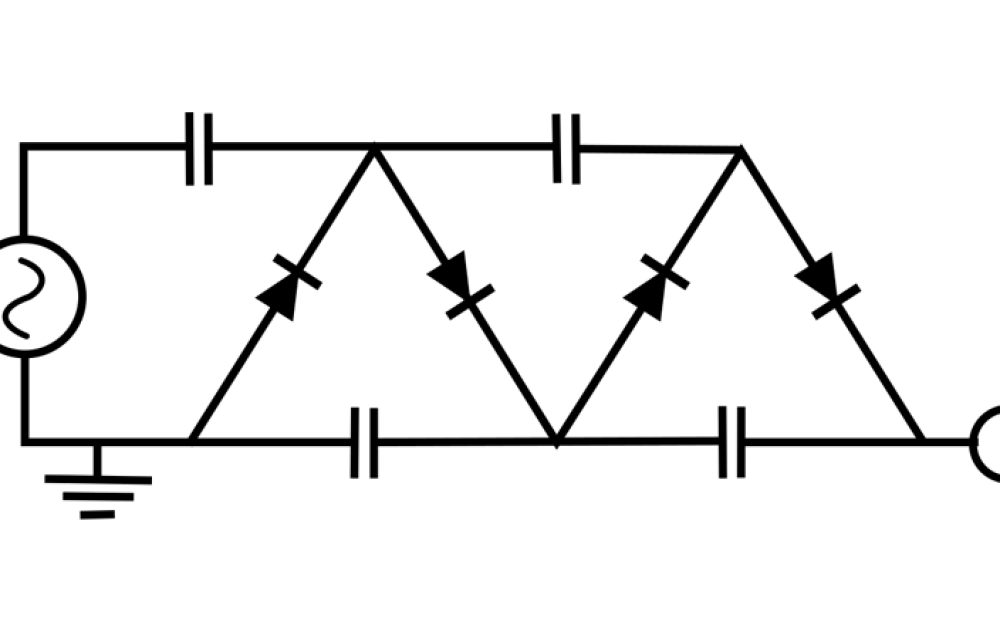

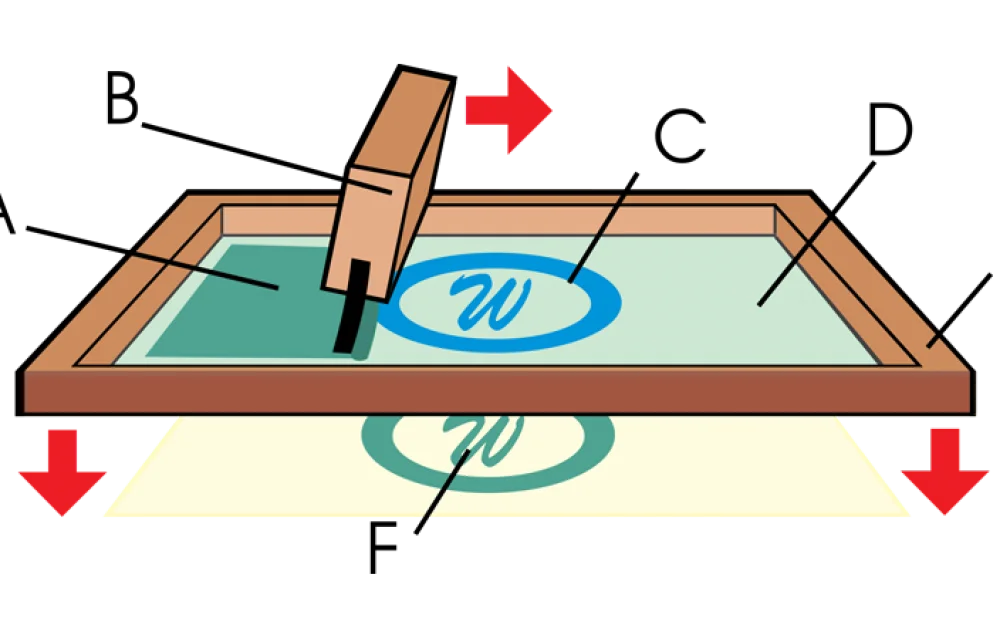

Sprayable (film) — the active substance acts both during sublimation and when it condenses as a thin film on the inner surface of the device’s bulb (the mirror of the gas absorbent).

Gas absorbents non-sprayable — do not require conversion to vapor phase followed by condensation as a mirror.

They can exist in a compact form (simple metals — titanium, zirconium, tantalum, thorium, niobium, or their alloys) as structural elements of the electrode system of the device, or entire electrodes, for example, focusing cylinders, anodes, grids, etc.

There are non-sputtering gas adsorbers in the form of powder coatings, which also serve as blackening agents (to enhance heat dissipation through radiation), for example, anodes of generator lamps. Typically, a getter of this type — "Ceto" — is a sintered mixture of aluminum with thorium and cerium metal (an alloy of cerium and lanthanum with impurities of other rare earth elements). A primer layer of nickel powder, sintered in a hydrogen atmosphere [6] at ~1100 oC, is first applied to the electrode. The getter powder with a binder (burnout binder) is then applied to the primed electrode, dried, and sintered in a vacuum at the same temperature.

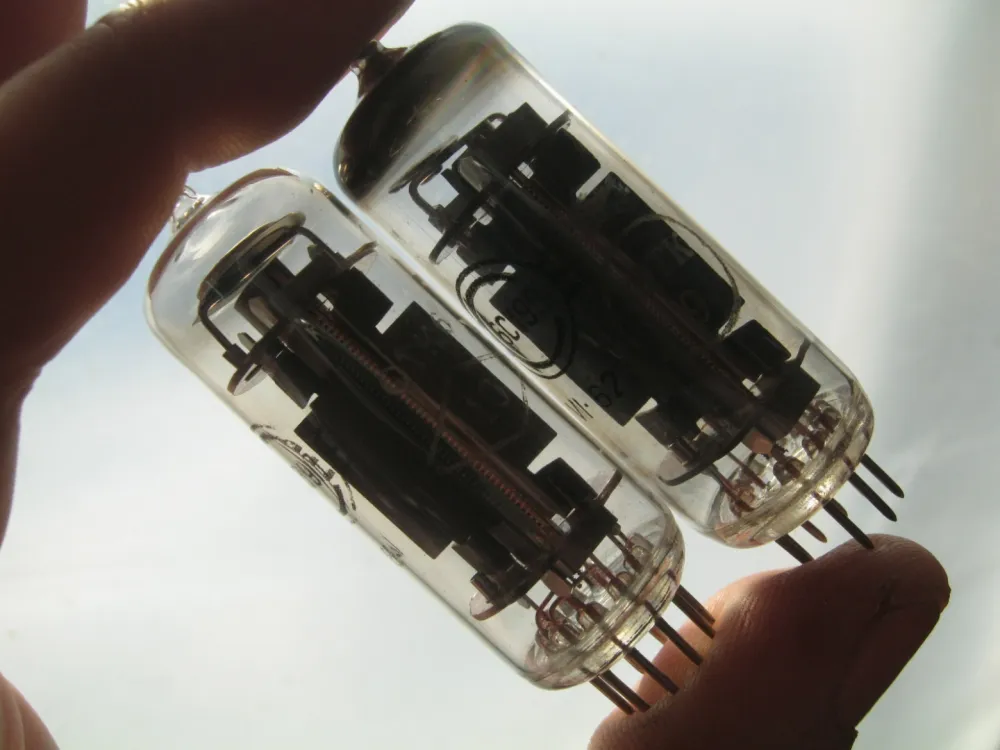

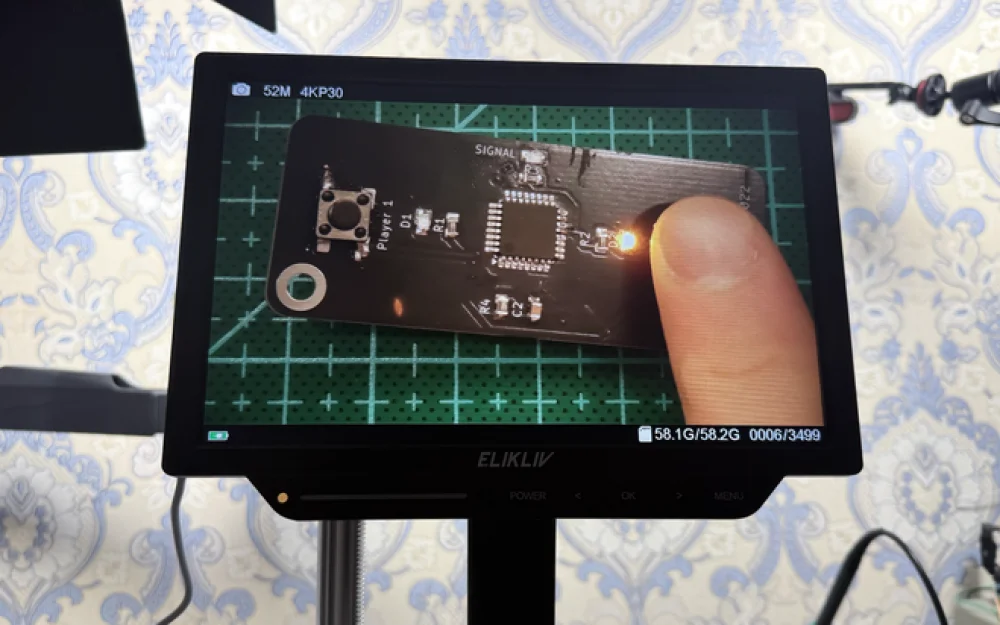

Another variant of non-sputtering gas adsorbers is compact high-porosity materials, manufactured in the form of separate blocks (Photo 4.1.), pressed without a binder and sintered in a vacuum. The raw materials are powders of titanium and the alloy "Cial" (84% zirconium, 16% aluminum) or a mixture of powders of titanium, "Cial," tungsten, and aluminum. High-porosity blocks immediately after manufacture become actively contaminated with gases and vapors present in the air, so they are re-fired (activated — heated) again in the evacuated lamp.

Non-sputtering gas adsorbers operate at temperatures higher than film adsorbers, which is their main drawback. At temperatures up to 600 oC, only surface absorption of vapors and gases occurs, and only after 700 oC does bulk absorption begin with the dissolution of gases and vapors in the mass of the getter and diffusion of contaminants into its thickness.

The components of non-sputtering gas adsorbers interact better with various gases and vapors at different temperatures — by placing them in different parts of the device, it is possible to flexibly regulate the absorption process and the composition of the residual atmosphere in the lamp.

Non-sputtering gas adsorbers have a greater (than film adsorbers) capacity and gas absorption rate, do not contaminate the electrodes and insulators of the device with sputtered metal, and allow for a denser arrangement of the electrode system.

The delineation provided, however, is not entirely strict — when dispersed in a vacuum, for example, through cathode bombardment, many metals, sometimes even unexpected ones, are capable of binding residual gases in the device bulb [7], more or less effectively.

5. Getter Materials for Incandescent Lamps

A vivid example of chemisorption is the classic phosphorus gas absorbent in vacuum (pumped down to a pressure of ~10-3 Torr) and gas-filled incandescent lamps (IL) of medium power [8].

The filaments of IL are usually made of pure tungsten, which is not as sensitive to contamination and foreign gases as oxide cathodes. The greatest danger here comes from the vapors of water, which form a continuous cycle of its transfer onto the glass of the bulb with heated W, and oxygen, which oxidizes W, with these oxides easily evaporating and settling on the bulb and cooler elements of the lamp, damaging the filament and reducing the lifespan of the device.

Carefully purified from impurities and finely ground red phosphorus (the same applies to sulfur, arsenic, iodine) along with some binder, in the form of a suspension, is applied to the filament or its current leads and evaporates at the first turn-on, turning into white phosphorus, which binds oxygen into colorless phosphorus pentoxide. Phosphorus pentoxide then reacts with vapors of water, forming a stable and also colorless metaphosphoric acid. The resulting substances settle on the walls of the bulb, practically not reducing the luminous efficacy of the device.

Fluoride compounds of alkali metals are additionally introduced into the phosphorus suspension, which also evaporate and form a colorless coating on the lamp bulb. Their task is to convert opaque W or its oxides, which have managed to form and evaporate from the filament, into transparent or lightly colored fluorides.

In early incandescent lamps, a sooty (as well as phosphor-sooty) gas absorber was used — the gas soot, obtained from the incomplete combustion of gaseous hydrocarbons, represents a loose form of carbon that intensely absorbs O2 from the air and binds O2 from water vapor. Such a type of getter was abandoned due to the formation of tungsten carbide and the deterioration of the mechanical properties of the filament.

A portion of soot was also used as a reducer of metallic barium from oxide, as part of barium-sooty getters in some gas-filled incandescent lamps. Carbon dioxide would thermally decompose barium carbonate into oxide, which would then be reduced by carbon to pure metal. The carbon dioxide released in the reaction was pumped out by pumps, and the lamp was sealed.

In powerful incandescent lamps, a non-evaporable getter was used — Al, Zr in the form of a thin layer on components in the hot areas of the lamp.

6. In Summary

Modern evaporated getters are geared towards refined mass production — precisely repeatable conditions, feedback. Many of the getters of both types have complex compositions and require significant and complicated preparatory work. Early gas absorbers, besides their technical history, are also of interest to hobbyists — despite their relatively low efficiency, ancient processes are much simpler and more accessible for replication in amateur laboratories and workshops, especially since typical "lighting" getters were successfully used in the first electronic lamps.

To be continued.

7. Additional materials

Electrovacuum getter, gas release, gas absorption in EVPs. Author's summary.

Deshman S. Scientific foundations of vacuum technology. Publishing House of Foreign Literature, Moscow, 1950.

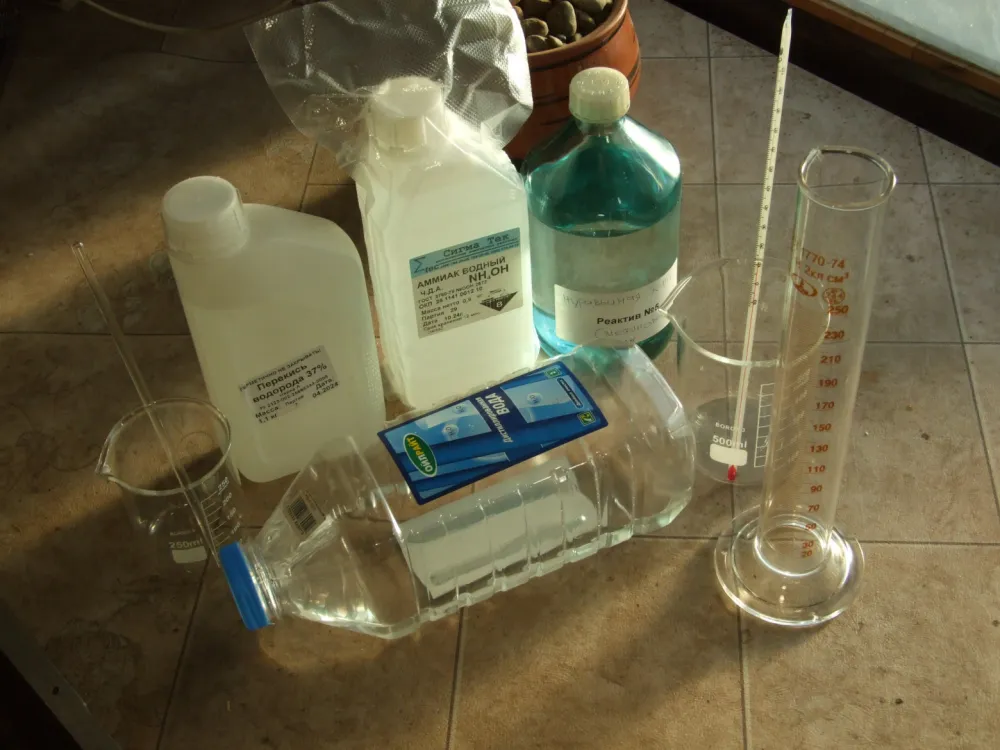

Electrovacuum chemistry in a home workshop. Etching of copper, nickel, molybdenum, tungsten. Author's summary.

Hydrogen furnaces in electrovacuum production. What, why, which ones? Author's summary.

Geissler tube — vacuum pump. Getter spraying by discharge. Author's summary.

The legendary vacuum triode of the 1920s — TM. History, design, characteristics. Author's summary.

For the benefit of all rational beings, Babay Mazay, January 2026.

© 2026 LLC "MT FINANCE"

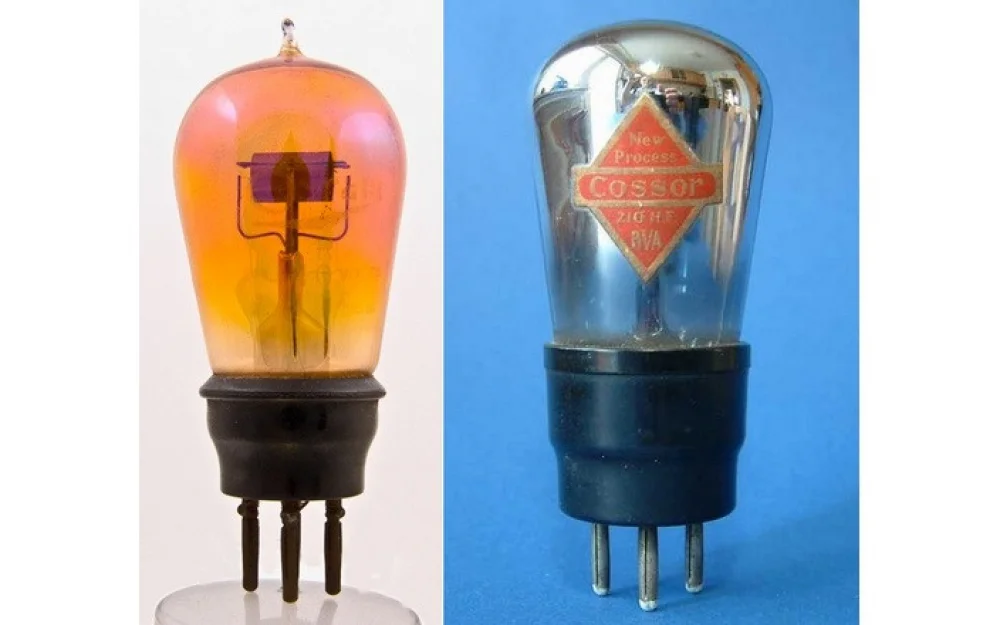

![Photo 6.1. Directly heated, "bright" — with a pure tungsten filament, type R triode, early 1920s — British, with a vertical anode, variant of the legendary French TM [9]. The reddish color of the bulb is due to excess phosphorus getter. Indeed, early electronic lamps did not differ much from lighting lamps and were even produced in the same factories, which is why the first radio tubes were packed in spherical bulbs. With phosphorus dosage, for obvious reasons, one could also afford not to be too fussy here.](https://cdn.tekkix.com/imgs/2026/02/habrcom/content/932b786b9987bf689d309134910f.webp)

Write comment